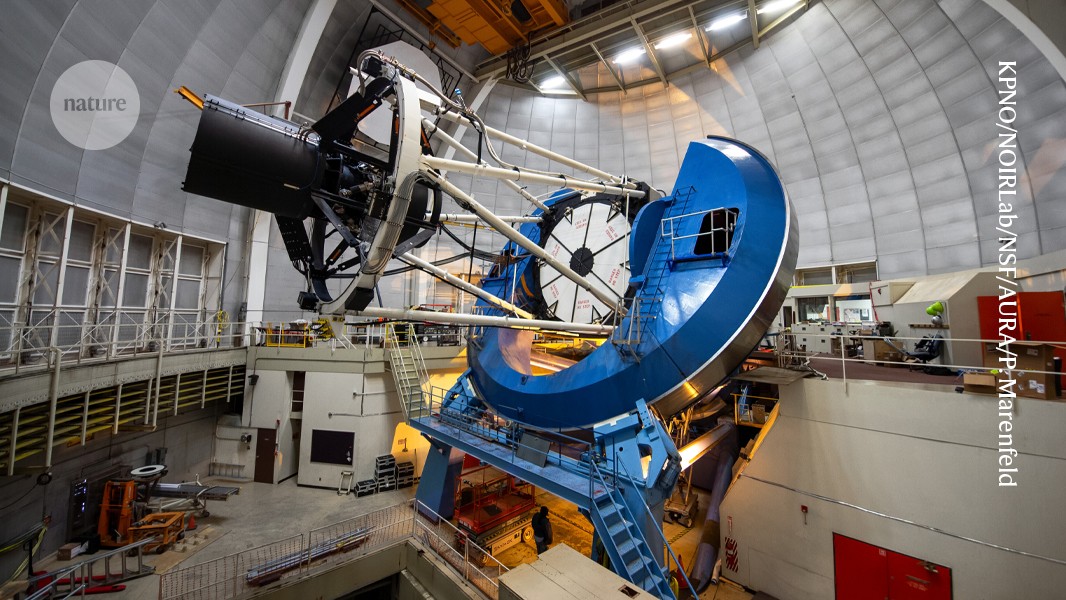

Part of the DESI telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona.Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/P. Marenfeld

Fresh data have bolstered the discovery that dark energy, the mysterious force that makes galaxies accelerate away from each other, has weakened over the past 4.5 billion years.

The effect was first tentatively reported in April last year, but the latest results — presented on 19 March by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) collaboration at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Anaheim, California — are based on three years’ worth of data-taking, versus one year for the results announced in 2024.

“Now I’m really sitting up and paying attention,” says Catherine Heymans, an astronomer at the University of Edinburgh, UK, and the Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

If the findings hold up, they could force cosmologists to revise their ‘standard model’ for the history of the Universe. The model has generally assumed that dark energy is an inherent property of empty space that does not change over time — a ‘cosmological constant’.

“The gauntlet has been thrown down to the physicists to explain this,” says Heymans.

Cosmic mapping

The DESI telescope is located at Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona. It uses 5,000 robotic arms to point optical fibres at selected points where galaxies or quasars are located within its field of view. The fibres then deliver light to sensitive spectrographs that measure how much each object is redshifted — meaning the degree to which its light waves were stretched by the expansion of space on their way to Earth. Researchers can estimate an object’s distance using its redshift, to produce a 3D map of the Universe’s expansion history.

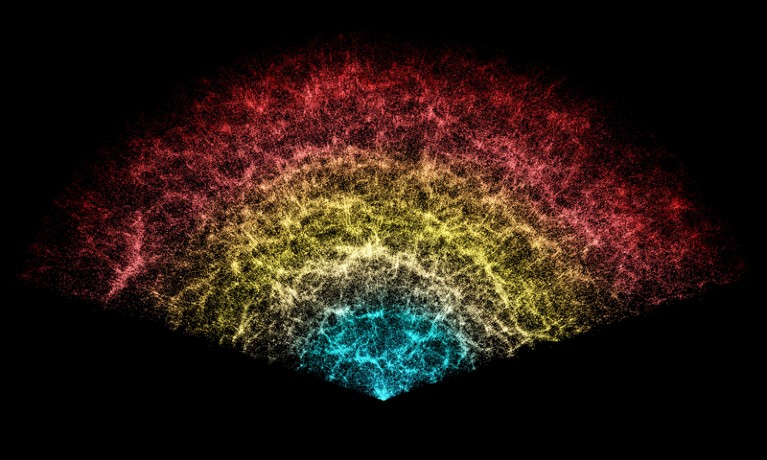

In that map, researchers then look at the density of galaxies to identify variations that are left over from sound waves called baryon acoustic oscillations (BAOs), which existed before stars began to form. Those variations have a characteristic scale that started out at 150 kiloparsecs (450,000 light years) in the primordial Universe and has been increasing with the cosmic expansion; they have now grown by a factor of 1,000 to 150 megaparsecs across — making them the largest known features in the current Universe.

A slice of the 3D map of galaxies based on data collected by DESI in the first year of its survey. Credit: DESI Collaboration/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Proctor

By tracking the evolving size of BAOs, researchers can reconstruct how the Universe’s rate of expansion has changed over the eons. Around 5 billion years ago, the expansion switched from decelerating to accelerating under the push of dark energy. Until last year, cosmology data were all consistent with dark energy being a cosmological constant — which meant that the Universe should continue to expand at an increasingly fast rate.

But the results of DESI’s latest analysis imply that the cosmic expansion is accelerating less now than it was in the past, which does not fit the assumption that dark energy is a cosmological constant. Instead, the data suggest that its energy density — the amount of dark energy per cubic metre of space — is now around 10% lower than it was 4.5 billion years ago.