Recombinant proteins

The vector pCPH6P-HIV1-IN used for bacterial expression of HIV-1 IN with a cleavable hexahistidine (His6) tag was previously described45. To obtain pCPH6P-SIVtal-IN, the DNA region encoding HIV-1 IN was replaced with a codon-optimized fragment encoding SIVtal IN (the corresponding amino acid sequence was derived from NCBI GenBank entry CAJ57812)46. HIV-1 and SIVtal INs were produced in endonuclease-A-deficient Escherichia coli PC2 cells (BL21(DE3), endA::TetR, T1R, pLysS)47 transformed with pCPH6P-HIV1-IN and pCPH6P-SIVtal-IN, respectively. The cells were grown in LB medium containing 120 μg ml−1 ampicillin to an absorbance at 600 nm (A600) of around 0.9 and supplemented with 50 μM ZnCl2, and protein expression was induced by addition of 0.01% (w/v) isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h at 30 °C. Bacterial cells were lysed by sonication in core buffer containing 1 M NaCl and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). To prevent aggregation of HIV-1 IN, all buffers used during purification of this protein were supplemented with 7.5 mM 3-((3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS); the detergent was not required and was avoided during purification of SIVtal IN. The supernatant was precleared by centrifugation and incubated with NiNTA agarose (Qiagen) for 1 h °C at 4 °C in the presence of 15 mM imidazole to capture His6-tagged proteins. The resin was washed extensively in core buffer supplemented with 15 mM imidazole, and the protein was eluted with 200 mM imidazole in core buffer. To remove the hexahistidine tag, the eluate was incubated with human rhinovirus 14 3C protease (1:50 (w/w) ratio) overnight at 4 °C in the presence of 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Cleaved proteins were diluted with ice-cold 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 to adjust NaCl concentration to around 150 mM and immediately injected into a precooled 5 ml HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare). A linear 0.15–1 M NaCl gradient in 7.5 mM CHAPS, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 (for HIV-1 IN) or 30 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5 (SIVtal IN) was used to elute the proteins; peak fractions were combined, supplemented with 1 mM DTT and the NaCl concentration was adjusted to 1 M. HIV-1 and SIVtal INs were concentrated using a 10-kDa cut-off Vivaspin device (Generon) to 8–10 and 1 mg ml−1, respectively, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

BLI analysis

All of the experiments were conducted using the Octet R8 instrument (Sartorius) at 25 °C in base buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 and 10 U ml−1 SUPERaseIn RNase inhibitor (LifeTechnologies, AM2696); sensorgrams were recorded using Octet BLI Discovery Software (Sartorius). Biotinylated RNA oligonucleotides (10 or 20 nM; Integrated DNA Technologies) were immobilized on Octet Streptavidin biosensors to reach 0.2 nm wavelength shift threshold in base buffer. The sensors were moved to wells containing 0.5, 0.25 or 0.125 μM HIV-1 or SIVtal IN in base buffer, and IN binding was recorded for 300 s. Dissociation was recorded for 300 s in the same buffer without IN. In control experiments, sensors without immobilized RNA were exposed to varying IN concentrations to test for non-specific binding.

HDX–MS

Individual proteins and protein–RNA complexes (3 µM, final) were incubated with 40 µl D2O buffer for 3, 30 and 180 s at room temperature in triplicate. The labelling reaction was quenched by adding chilled 2.4% (v/v) formic acid in 2 M guanidinium hydrochloride and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at −80 °C before analysis. The quenched protein samples were rapidly thawed and processed for proteolytic cleavage by pepsin followed by reversed-phase HPLC separation of the resulting peptides. In brief, the protein was passed through an Enzymate BEH immobilized pepsin column (2.1 × 30 mm, 5 µm, Waters) at 200 µl min−1 for 2 min and the peptic peptides were trapped and desalted on a 2.1 × 5 mm C18 trap column (Acquity BEH C18 Van-guard pre-column, 1.7 µm, Waters). Trapped peptides were subsequently eluted and separated over 11 min using a 5–43% gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid at 40 µl min−1. Peptides were separated on a reverse-phase column (Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column 1.7 µm, 100 mm × 1 mm; Waters). Peptides were detected on the Cyclic mass spectrometer (Waters) acquiring over an m/z of 300 to 2,000, with the standard electrospray ionization source and lock mass calibration using [Glu1]-fibrino peptide B (50 fmol µl−1). The mass spectrometer was operated at a source temperature of 80 °C with a spray voltage of 3.0 kV. Spectra were collected in positive-ion mode.

Peptide identification was performed by MSe software48 using an identical gradient of increasing acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid over 12 min. The resulting MSe data were analysed using Protein Lynx Global Server software (Waters) with an MS tolerance of 5 ppm. Mass analysis of the peptide centroids was performed using DynamX software (Waters). Only peptides with a score >6.4 were considered. The first round of analysis and identification was performed automatically by DynamX software; however, all peptides (deuterated and non-deuterated) were manually verified at every timepoint for the correct charge state, presence of overlapping peptides and correct retention time. Deuterium incorporation was not corrected for back-exchange and represents relative, rather than absolute changes in deuterium levels. Changes in hydrogen–deuterium amide exchange in any peptide may be due to a single amide or a number of amides within that peptide. All timepoints in this study were prepared at the same time and individual timepoints were acquired on the mass spectrometer on the same day. The MS data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium through the PRIDE49 partner repository under dataset identifier PXD070910.

SEC–MALLS analysis

For size-exclusion chromatography coupled to multiangle laser light scattering (SEC–MALLS) analysis, SIVtal IN (100 μl) in 0.5 M NaCl, 3 mM NaN3, 0.5 mM Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was injected onto the Superdex-200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva) equilibrated in the same buffer. Chromatography was performed at 25 °C, at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 using the JASCO-4000 semimicro HPLC system. Scattered light intensities and protein concentrations in the eluate were measured using the DAWN-HELEOS II laser photometer and an OPTILAB-TrEX differential refractometer (Wyatt Technology), respectively. The data were analysed using ASTRA software v.7.3.2 (Wyatt Technology) using recordings from both detectors, assuming a specific refractive index increment (dn/dc) of 0.186 ml g−1. The weight-averaged molar mass of SIVtal IN in chromatography peaks was determined from the combined data of three independent experiments with IN diluted to 1, 0.5 and 0.25 mg ml−1.

Cryo-EM data collection on the SIVtal IN–RNATAR complex

Graphene oxide grids were prepared as previously described50. In brief, UltrAuFoil R1.2/1.3 grids (Quantifoil) were pretreated in a glow discharge unit (GloQube Plus, Quorum) for 5 min at 25 mA, and then incubated with 4 µl 0.22 mg ml−1 graphene oxide flake suspension (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 min. Synthetic RNA (Integrated DNA Technologies) diluted in RNase-free water to 1.175 µM, was incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and cooled on ice. SIVtal IN–RNA complexes were assembled by combining IN (prepared in 0.5 M NaCl, HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5) and RNA at final concentrations of 4 µM (0.13 mg ml−1) and 1 µM, respectively, in 0.15 M NaCl, 25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0. The mixture (4 µl) was immediately applied to a graphene-oxide-coated grid. The grids were blotted on both sides for 4 s in a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI, Thermo Fisher Scientific) instrument at 4 °C and 95% humidity and vitrified by plunging into liquid ethane-propane. Blotting paper was from Agar Scientific (47000-100), and the blot force was set to −1.

Data collection was performed on the Titan G2 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 300 kV and equipped with a Falcon 4i direct electron detector and a Selectris energy filter (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Extended Data Table 1). Micrographs were recorded using EPU software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the dose-fractionation mode, at a calibrated magnification corresponding to 0.95 Å per physical pixel and a total sample exposure dose of 40.3 e− Å−2. A total of 38,395 micrograph movies was collected (3 per foil hole) automatically using EPU software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an energy filter slit set to 10 eV and a defocus range −1 to −4 µm. In total, 1,674 EER frames, recorded per micrograph movie, were subsequently processed in 31 fractions, with an exposure dose of 1.3 e− Å−2 per fraction. The movie frames were aligned with dose weighting using Relion-4.0 (refs. 51,52), and contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters were estimated from frame sums using Gctf-v1.18 (ref. 53).

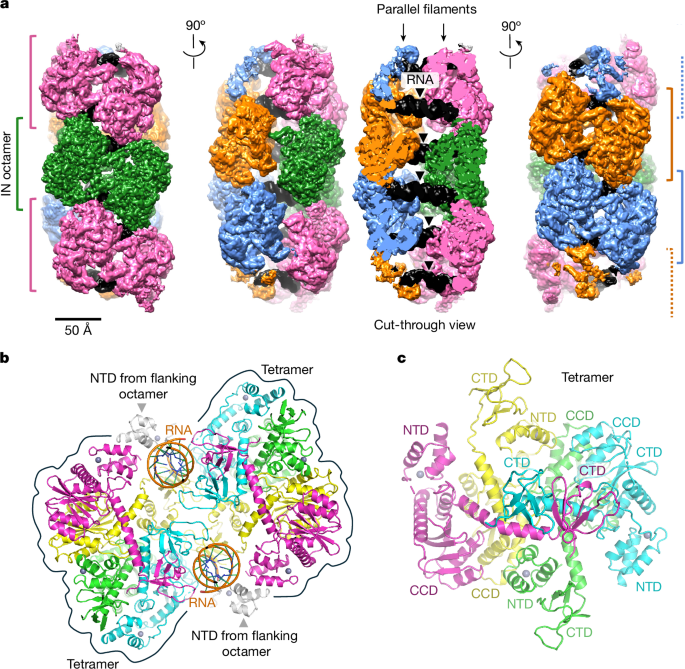

Single-particle image processing and structure refinement of the SIVtal IN–RNATAR complex

An initial set of particles picked using crYOLO with the general model54 were processed for reference-free 2D classification in cryoSPARC-4.6.2 (ref. 55). Particles belonging to well-defined 2D classes were used to train a model for particle picking in Topaz56. The entire dataset was picked with Topaz using the trained model and with Gautomatch-v0.56 (https://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/kzhang/Gautomatch/), using 2D class averages (low-pass filtered to 18 Å) as templates. Particles, extracted with pixel size 3.8 Å, were processed for several rounds of 2D classification in cryoSPARC, and those contributing to well-defined 2D classes (Extended Data Fig. 3a) were re-extracted with a pixel size 1.9 Å for tandem ab initio reconstruction and heterogenous refinement in cryoSPARC into three classes. Particles from the Topaz- and Gautomatch-picked subsets belonging to a single well-defined 3D class were combined, pruned of duplicates using the relion_star_handler tool with a proximity cut-off of 35 Å and used for training an optimized Topaz model. The entire dataset was picked again using Topaz with the new model, and the particles underwent the same image processing, including 2D classification, ab initio reconstruction into three classes followed by heterogenous refinement in cryoSPARC. Particles from a single well-defined 3D reconstruction from each separately picked set were combined and filtered for duplicates with a proximity cut-off of 35 Å. The resulting 181,089 particles, re-extracted without binning, were processed for tandem ab initio reconstruction and heterogenous refinement in cryoSPARC into three classes, yielding a single well-defined class comprising 170,999 particles. Non-uniform refinement of these particles resulted in a 3D reconstruction at an overall resolution of 4.3 Å with C2 symmetry imposed. To take advantage of the translational symmetry, the particle set was expanded by extracting potentially new particles offset by one repeat length in both directions along the IN polymer axis (98 micrograph pixels in either direction along the y axis of the reconstruction). The expanded dataset, pruned for duplicates, was processed for two rounds of tandem cryoSPARC ab initio reconstruction and heterogenous refinement into three classes, yielding a subset of 182,209 particles. This translation symmetry expansion procedure was repeated one more time, resulting in 225,773 particles affording a 3D reconstruction at 4.1 Å resolution with C2 symmetry imposed. An additional round of purification by tandem ab initio reconstruction and heterogenous refinement into two classes yielded a subset of 219,353 particles. Non-uniform refinement of these particles resulted in a 3D reconstruction at 4.0 Å resolution with C2 symmetry imposed, which was used for per-particle CTF refinement in cryoSPARC and Bayesian polishing in Relion-4.0. At this stage, local refinement in cryoSPARC with a soft mask around a single IN octamer repeat unit and the associated RNA chains produced a 3D reconstruction at a resolution of 3.5 Å using C2 symmetry. The refined particles were sorted into six 3D classes without realignment in Relion while imposing a soft mask focusing on a single repeat unit plus associated RNA and the regularization parameter T = 4; 102,121 particles contributing to the high-resolution class allowed a local reconstruction at an overall resolution of 3.3 Å using C2 symmetry. To select particles with best-ordered RNA chains, locally refined particles were processed for the particle subtraction procedure to remove signal contributed by IN subunits followed by 3D classification without realignment and without imposing symmetry into five classes with a soft mask focusing on the RNA subunits and the regularization parameter T = 4, as implemented in Relion. CryoSPARC global non-uniform and local refinement of the selected best 53,737 particles produced the final reconstructions at 3.7 and 3.3 Å resolution, respectively, using C2 symmetry (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c and Extended Data Table 1).

The resolution metrics reported here are according to the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) 0.143 criterion57,58. Local resolution of the 3D reconstruction was estimated in cryoSPARC (Extended Data Fig. 3c). For illustration purposes and to aid in model building, the cryo-EM map was processed with EMReady-v2 (http://huanglab.phys.hust.edu.cn/EMReady2/)43; for real-space refinement of the atomistic model, the reconstruction was sharpened and filtered as implemented in cryoSPARC based on local resolution metrics.

The model of the SIVtal IN–RNA complex was initially assembled by rigid body docking of individual HIV-1 IN domains (from PDB 1K6Y (ref. 14), 8A1P (ref. 36) and 5TC2) in the cryo-EM map using UCSF Chimera59. Because the orientation (and possibly register) of the HIV-1 TAR stem loop is undetermined, the RNA was modelled as an oligo-A/U duplex. The model was adjusted in Coot60 to match the amino acid sequence of SIVtal IN and refined using phenix.real_space_refine (v.1.21.2-5419)61. The quality of the final model was assessed using MolProbity62 (Extended Data Table 1). Structural images were generated using UCSF Chimera59 and PyMOL (https://www.pymol.org/).

Cryo-EM of SIVtal IN in the absence of RNA and in the presence of (GA)18 ribooligonucleotide

SIVtal IN in the absence of RNA was prepared and vitrified on graphene-oxide-coated holey carbon grids exactly as described for the IN–RNA complex. In total, 3,220 micrograph movies were recorded on a 200 kV Glacios microscope using a Falcon 3 direct electron detector operated in linear mode at a calibrated magnification corresponding to a pixel size of 1.24 Å with accumulated total specimen exposure of 53 e− Å−2, spread over 10 fractions and a defocus range of −1.5 to −3.5 μm. Micrograph movie frames were aligned and combined using MotionCor2 (v.1.4.0)63 with dose weighting, and CTF parameters were estimated from frame sums using Gctf (v.1.18)53. The micrographs revealed sparse patches of aggregated material without obvious regular supramolecular assemblies. Accordingly, no well-defined 2D class averages were obtained with particles picked using crYOLO v.1.9.6 with general model (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

To image SIVtal IN-(GA)18 complexes, a sample containing 4 μM SIVtal IN and 1 μM ribooligonucleotide in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 8.0) was vitrified on an UltrAufoil 1.2/1.3 300-mesh grid, using the Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI, Thermo Fisher Scientific) instrument at 4 °C and 95% humidity. The grid was pretreated in the GloQube Plus glow discharger (Quorum) at 25 mA for 1 min. The sample was spotted onto the grid twice (10 μl each time) with blotting between the applications (3.5 s blot time, force −10, 10 s wait time, 4 °C). In total, 40,377 micrograph movies were recorded on the Titan Krios microscope equipped with a Falcon 4 camera and processed as described above for the SIVtal-RNATAR complex. The images revealed the presence of well-defined linear IN polymers (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Iterative rounds of particle picking and 2D classification resulted in well-defined 2D averages consistent with formation of single IN filaments (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Owing to strong preferential orientation with only top and side views present, further image processing did not yield a high-quality 3D reconstruction.

Preparation of HIV-1 cores for cryo-EM, data collection and preprocessing

Lenti-X HEK293T cells (Takara Bio, 632180) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified minimal medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Life Technologies) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were negative for mycoplasma, as evidenced via regular monthly testing with the MycoAlert mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza, LT07-218). The IN-coding region in pVpr-mNeonGreen-IN64 was modified with D64N and D116N mutations to abrogate the active site in the protein product. To produce HIV-1 virions, Lenti-X HEK293T cells grown in two T175 flasks to around 70% confluence, were transfected with pNLC4-3 IN D64N/D116N tatΔ33-64bp25 and pVpr-mNeonGreen-IN(D64N,D116N) (29 µg and 9.7 µg per flask, respectively) or with NLC4-3 IN D64N/D116N tatΔ33-64bp alone (39 µg per flask) using polyethyleneimine (64 µg per flask) in OptiMEM medium (Life Technologies). The next day, the medium was changed to DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Virus-containing supernatant collected 48 h after transfection was precleared by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min and passed through a 0.45-µm filter. Viral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a cushion of 20% sucrose in ST buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl) supplemented with 1 mM inositol hexaphosphate (ST/IP6) in a SW32Ti rotor at 30,000 rpm for 3 h. The glassy green pellet containing viral particles was resuspended in ST/IP6. To isolate cores, concentrated viral particles were processed for ultracentrifugation through a layer of 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 into a linear 30–85% (w/v) sucrose gradient (made in ST/IP6) as previously described65. Fractions containing cores, identified by NG fluorescence or by the presence of reverse transcriptase activity (measured using a quantitative PCR assay66 adapted for TaqMan technology67), were dialysed against ST/IP6 to remove sucrose. The fractions were analysed by western blotting (Extended Data Fig. 4c) with mouse monoclonal anti-HIV-1 CA antibody ARP-6458 (obtained through the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, contributed by M. H. Malim) and rabbit polyclonal anti-HIV-1 IN antibody68, diluted at 1:5,000 and 1:10,000, respectively. Signals were developed using horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Dako, P0447, 1:10,000) and swine anti-rabbit antibodies (Dako, P0399, 1:10,000) in conjunction with ECL Select detection reagent (Cytiva, RPN2235).

R2/2 300-mesh holey carbon grids (Quantifoil) were glow discharged using a PDC-002-CE plasma cleaner (Harrick Plasma) instrument at 100 mA for 45 s in air. Dialysed cores (3.5 μl) were applied to a pretreated grid under 95% humidity at 20 °C, before blotting and plunge-freezing in liquid ethane-propane using a GP2 Automatic plunge freezer (Leica Microsystems). Vitrified HIV-1 cores were imaged on a 300 kV Titan Krios G2 cryo-electron microscope equipped with a Falcon 4i direct electron detector and a Selectris energy filter (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Extended Data Table 1).

For structural analysis of the cores with supplemental IN, we used single-particle cryo-EM approaches that were previously used for 3D reconstruction of the CA lattice within in vitro assembled capsid-like particles69,70,71. Data were recorded using EPU software in dose-fractionation mode, at a calibrated magnification corresponding to 0.95 Å per physical pixel. 1,674 EER frames collected per micrograph movie were subsequently processed in 31 fractions, with an exposure dose of 1.6 e− Å−2 per fraction. A total of 47,025 micrograph movies was recorded (9 per foil hole) using EPU software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an energy filter slit width of 10 eV and a defocus range set at −1.5 to −3.5 µm. The micrograph movie frames were aligned with dose weighting as implemented in Relion (v.4.0)51,52, and CTF parameters were estimated from motion corrected images using Gctf (v.1.18)53.

Native cores isolated from HIV-1 particles without supplemental Vpr-NG-IN were studied by cryo-ET. The tilt series, each from −60° to +60° with 3° increments, were acquired using Tomography software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the dose-symmetric scheme72, a total exposure of 104 e− Å−2 (2.5 e− Å−2 per tilt image), a calibrated magnification resulting in a pixel size of 1.56 Å and a defocus range of −2.5 to −5.5 µm. Each tilt micrograph movie stack containing six frames in TIFF format was motion-corrected and summed in WarpTools73. Tilt images were aligned using patch tracking in IMOD74, and CTF-corrected tomograms were reconstructed with WarpTools. To create illustrations, the tomograms were denoised using DeepDeWedge75. Reconstructed tomograms were visualized using ChimeraX76,77 with ArtiaX plug-in78.

Single-particle cryo-EM image processing of HIV-1 cores with excess IN

YOLOv11, a deep-learning tool developed for general computer vision tasks (https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/), was used to identify HIV-1 cores on micrographs. The small YOLOv11 model (yolo11s.pt, with 9.44 million parameters) was trained on a carefully curated subset of 595 micrographs containing 2,578 manually boxed cores. The training set additionally included 137 null examples, that is, micrographs lacking recognizable cores but containing full range of contaminating signal (crystalline ice, carbon edges and cellular debris) present. Manual annotation was done using Roboflow (https://app.roboflow.com), while model training and core detection used resources provided by GoogleColab (https://colab.research.google.com). JPEG copies of the micrographs (512 × 512 pixels), produced by the EPU software, were suitable for model training and core detection. The following parameters were used during training: model=yolo11s.pt, epochs=600, imgsz=640, patience=200, and the model reached mean average precision values mAP50 and mAP50–95 of 0.856 and 0.528, respectively. The model, applied to the entire dataset with confidence parameter set to 0.25, predicted a total of 120,747 cores, each defined by a rectangular bounding box (Extended Data Fig. 5a). All downstream image processing was done on 20,214 micrographs comprising 43% of the dataset, containing at least one core identified by YOLOv11.

The micrographs were picked exhaustively using a hierarchical four-step approach. Initially, particles were picked within each core bounding box with regular grid spacing of 120, 150 and 180 micrograph pixels. As some cores overlapped on the micrographs, each resulting particle set was filtered to remove duplications, allowing not less than 100 micrograph pixels (95 Å) between picked centres. The resulting 4,218,210 (spaced by 120 pixels), 2,837,521 (150 pixels) and 2,094,749 (180 pixels) particles extracted with a box size of 90 px (binned fourfold to 3.8 Å per pixel) were processed for 4–6 rounds of 2D classification in cryoSPARC, using 200 classes, a batch size of 400 particles per class and 50 on-line EM iterations. Particles belonging to well-defined 2D classes (Extended Data Fig. 5b) were used for ab initio reconstruction followed by heterogenous refinement in cryoSPARC using five classes (Extended Data Fig. 5c). 3D classes refining as a hexameric CA lattice from each subset were combined and pruned of duplicates enforcing a minimal distance cut-off of 60 Å, resulting in a subset of 495,638 particles. These were re-extracted with a box size of 120 pixels (binned fourfold to a pixel size of 3.8 Å) and processed for purification by heterogenous refinement in cryoSPARC (v.4.6.2) using two initial volumes: a refined reconstruction of the hexameric CA lattice obtained at the previous stage and a junk trap prepared by phase randomization of Fourier components with spatial frequences exceeding 1/40 Å−1. The initial resolution was set to 15 Å and refinement box size to 120 pixels, with the rest of the parameters left at default values. The 235,835 particles remaining after three consecutive rounds of heterogenous refinement, re-extracted with pixel size of 1.9 Å, were processed for the heterogenous refinement procedure with a phase randomized junk trap. This time, the initial resolution was set to 12 Å and the refinement box size was set to 160 pixels. After three rounds of heterogenous refinement, the purified subset comprised 179,033 particles (crude set 1); non-uniform refinement of these particles without and with C2 symmetry imposed resulted in 3D reconstruction of the CA lattice at 5.8 and 4.7 Å, respectively.

The particles were used to train a custom Topaz56 model. The micrographs were repicked with Topaz using the trained model and with Gautomatch v.0.56 (https://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/kzhang/Gautomatch/) using 2D class averages showing a well-defined CA lattice, low-pass-filtered to 18 Å resolution, as templates to repick the entire dataset. In total, 10,542,672 Topaz-picked and 3,689,441 Gautomatch-picked particles (found within YOLOv11 identified core bounding boxes) were extracted, binned fourfold and processed using the procedure detailed above, including consecutive rounds of 2D classification, heterogenous and non-uniform refinement (imposing C2 symmetry at the final stage), yielding subsets of 477,807 and 443,013 aligned particles (crude sets 2 and 3, respectively). At this point, particles picked by the three methods (crude sets 1–3) were combined and filtered for duplications, imposing a minimal distance of 30 Å, resulting in a subset of 808,938 particles.

Global refinement of the combined particle set generated a reconstruction at a resolution of around 4.5 Å, and the alignment parameters were used to erase signal contributed by the CA lattice using particle subtraction procedure in Relion (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Modified particles were processed for 45 iterations of 3D classification into 7 classes without realignment in Relion with a soft semi-cylindrical mask focusing on the volume underlying the CA lattice and T value set to 2 (Extended Data Fig. 5d); the starting model was the original 3D reconstruction low-pass filtered to 40 Å. The procedure isolated a class comprising 50,827 particles revealing a well-defined linear polymer of IN octamers (Extended Data Fig. 5d). These particles were used to train Topaz to repick the micrographs one more time. The resulting 5,795,765 particles were processed for 2D classification and heterogenous refinement yielding 219,985 aligned particles (crude set 4).

Crude sets 1–4 were combined and pruned for duplicates allowing a minimum of 30 Å between particle centres on micrographs, resulting in a collection of 975,484 particles. The particles, extracted with twofold binning, were processed for 3D autorefinement in Relion (imposing C2 symmetry), followed by subtraction of CA signal and 3D classification without realignment (with a semi-cylindrical mask focusing on the volume underlying CA lattice and using eight classes) as described above. The procedure yielded a single 3D class corresponding to a chain of IN octamers and comprising 59,749 particles. To take advantage of the translational symmetry of the IN filament, the particle set was expanded by adding potentially new particles off-set by one and two repeat lengths in either direction along the IN polymer. The translational symmetry-expanded particle set was pruned for duplicates allowing a minimal distance between particle centres of 10 Å. The resulting 280,358 particles were used in non-uniform refinement followed by 3D classification (without realignment) into eight classes in cryoSPARC with a soft semi-cylindrical mask encompassing the space underlying the CA lattice. The best-defined 3D class, comprising 43,320 particles, was processed for non-uniform refinement and one more round of translational symmetry expansion resulting in 138,637 non-overlapping particles. Following 3D classification in cryoSPARC, several rounds of non-unform refinement, duplicate pruning and CTF refinement in cryoSPARC, the final reconstructions were obtained through non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC (with C2 symmetry applied) using subsets comprising 58,103 and 46,116 particles to an overall resolution of 4.63 Å (with a box size of 240 × 1.44 Å, encompassing 1 IN octamer repeat unit and 4 complete CA hexamers) and 4.83 Å (332 × 1.44 Å, containing 3 complete IN octamers and 14 CA hexamers), respectively (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Extended Data Table 1). For illustration purposes and to aid in model building, the cryo-EM map was processed with EMReady v.2 (http://huanglab.phys.hust.edu.cn/EMReady2/)43. For real-space refinement of the atomistic model, the reconstruction was sharpened and filtered as implemented in cryoSPARC based on local resolution metrics.

The atomistic model was assembled by rigid-body docking CA hexamers (derived from PDB 6SKK)79 and individual IN domains (from PDB 1K6Y (ref. 14), 9C9M (ref. 44) and 8A1P (ref. 36)) into the cryo-EM map using UCSF Chimera59. The model was extended and locally refined in Coot60 followed by global refinement in Namdinator80. Two IP6 ligands were added per CA hexamer, based on the features of the cryo-EM map. The final model, derived by iterative cycles of improvement using Coot and phenix.real_space_refine (v.1.21.2-5419)61, had a good fit to the cryo-EM map and reasonable geometry, as assessed by MolProbity62 (Extended Data Table 1).

Subtomogram averaging of IN filaments inside native cores produced in the absence of Vpr-NG-IN

Fourteen tilt series that were sufficiently well aligned to produce tomograms with clearly discernible hexagonal CA lattice features (Extended Data Fig. 9a) were selected for further processing. An initial subset of particles was picked by template matching in CTF-corrected tomograms (reconstructed at 10 Å per pixel) using pytom-match-pick81. The template represented the CA lattice isolated from the single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction of cores produced in the presence of Vpr-NG-IN (47 × 47 × 47 nm3 box; see above). To minimize bias, features corresponding to IN were removed by segmentation in UCSF Chimera, and the resulting template was low-pass filtered to a resolution of 20 Å. A total of 2,375 subtomograms was extracted using Warp (3.02 Å per pixel; 192 pixel box size) and processed for 3D classification into six classes in Relion v.4.0. The initial reference, generated using relion_reconstruct from the extracted subtomograms (using the –ctf –3d_rot settings), was low-pass filtered to 60 Å. Classification was run for 45 iterations with a T value of 0.2, without symmetry imposed. This procedure yielded a single class comprising 164 particles showing a well-defined IN filament (Extended Data Fig. 9b). These filaments could also be visualized in denoised tomograms when oriented approximately parallel to the xy plane (Extended Data Fig. 9c). We found that the shape of CA lattice used for template matching was critical for identification of the subtomograms containing IN. This may be because the filaments prefer and/or induce specific local curvature of the core wall, which may explain orientation of the filaments along the sides of the cores (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Refinement of the subtomogram subset in Relion with a soft mask and C2 symmetry resulted in a reconstruction at an overall resolution of 19 Å. To exploit the translational symmetry of the IN filaments, additional subtomograms were extracted by shifting the original particles by ±1 and ±2 IN octamer repeat units along the filament axis. Duplicate subtomograms were removed using relion_star_handler with a distance cut-off of 60 Å, resulting in a total of 773 unique particles. These were re-extracted in Warp and processed for 3D classification in Relion into six classes (T = 1, no symmetry imposed), yielding a subset of 494 particles contributing to three well-defined classes. This dataset was expanded again using the same translational symmetry strategy, resulting in 1,065 subtomograms after duplicate removal. These were classified into seven classes (T = 1, no symmetry imposed), yielding a subset of 617 particles, which was further refined to 594 particles through an additional round of 3D classification into six classes (T = 1, no symmetry imposed). This final set of subtomograms was used for 3D refinement in Relion, with C2 symmetry and a soft mask, resulting in a reconstruction at an overall resolution of 12.6 Å, and local resolution of around 10 Å throughout most of the CA and IN regions (Extended Data Fig. 9d,e). A locally filtered map used to create illustrations was generated in cryoSPARC (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 9f).

IN–CA complex atomic model building for MD simulations

Before performing MD simulations, we prepared a model of the IN octamer–CA hexameric lattice complex based on the cryo-EM map and refined atomistic model using the following procedure. First, missing residues not resolved in the cryo-EM density, corresponding to the IN NTD-CCD linker (residues 42–54) and short segments in the CCD (residues 139–143) and CTD (residues 267–272), were modelled using the comparative modelling tool MODELLER (v.10.6)82,83 in ChimeraX76,77. For each IN chain in the octamer, five independent full-length models were generated using the cryo-EM derived structure and the IN sequence as templates. The model with the lowest DOPE score was selected for each chain, and the resulting models were combined into a complete IN octamer structure. Zn2+ cations coordinated by residues His12, His16, Cys40 and Cys43 in the IN NTDs were retained from the cryo-EM-derived structure. IN chain structures were consistent with the IN sequence used in the HIV-1 core samples. Thus, the IN model has the D64N and D116N amino acid substitutions, which precluded divalent metal ion coordination at the catalytic sites. The complete IN octamer structure was then combined with the CA hexameric lattice to generate a IN–CA complex model.

Hydrogen atoms were added on the basis of the predicted protonation state of the amino acids at pH 7.0, as determined using propKa3 (refs. 84,85). The protein complex was then solvated in a periodic box of TIP3P water molecules86,87 using the solvate plug-in in Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) v.1.9.4a57, compiled using Python (v.3.9)88. Na+ and Cl− ions were added to a concentration of 150 mM using the cionize and autoionize plug-ins in VMD88, while ensuring the charge neutrality of the solvated system. To minimize the simulation box volume, the orientation of the IN–CA complex was optimized using rigid-body rotations. A minimum distance of 10 Å was maintained between the protein and the edge of the solvent box, resulting in a system size of 284 Å × 245 Å × 162 Å. The total atom count of the solvated IN–CA system was 1,054,000 atoms.

MD simulation setup

As a further refinement step, we performed MD flexible fitting (MDFF)89 to refine the position of the protein backbone in accordance with the cryo-EM density. In MDFF, the cryo-EM density map is used as a grid-based potential applied to selected coupled atoms, biasing their motion to fit into the density. For MDFF, we first performed energy minimization, coupling the protein backbone and heavy atoms of IP6 to the cryo-EM density using the gridForces module in NAMD (v.3.0.1)90 with a gridScaling factor of 0.3 kcal mol−1 amu−1. The system was minimized for 35,000 steps using a conjugate gradient descent algorithm, ensuring that the gradient converged below 10 kcal mol−1 Å−2.

After minimization, we conducted a 10 ns equilibration of the system in an NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure and temperature), maintaining the coupling to the density with gridScaling factor (0.3 kcal mol−1 amu−1) to allow the protein backbone to dynamically adjust its fitting to the density. Temperature and pressure were maintained constant during equilibration at 310 K and 1 atm, respectively. Finally, to alleviate any internal strain introduced by the biasing potential, we performed a scheme of five sequential 35,000 step minimization runs, using progressively reduced gridScaling factors (5.0, 1.0, 0.5, 0.1, 0 kcal mol−1 amu−1). The resulting structure from the procedure previously described, was then used as the starting structure for subsequent simulations of the IN–CA complex.

MD production simulations

The resulting structure from the MDFF procedure was used as the starting model for four independent production simulations. Each replica simulated the IN–CA complex for 1 μs in an NPT ensemble, with grid force coupling applied to the protein backbone (for residues well resolved in the cryo-EM density) using a grid scaling factor of 0.3 kcal mol−1 amu−1. This coupling preserved the agreement of the IN–CA protein backbone with the observed density while allowing for side chains to interact freely throughout the simulation. Pressure was maintained at 1 atm using the Nose–Hoover Langevin piston, with a period of 200 fs and a decay time of 100 fs. Pressure control was configured to maintain the xy plane area of the system constant while allowing fluctuations in the z axis. The temperature was kept at 310 K using a Langevin thermostat with a damping constant of 1 ps−1.

All simulations used the CHARMM36m forcefield for proteins91 and the TIP3P-charmm model for water molecules86. Bonds between hydrogen and heavy atoms were constrained using the SHAKE92,93 and SETTLE94 algorithms. The simulation time step was set at 4.0 fs, enabled by the application of the hydrogen mass repartition scheme95,96, which redistributed mass from heavy atoms in the solute to their bonded hydrogen atoms. Non-bonded interactions were calculated with a 12 Å cut-off for short-range electrostatic interactions, while long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated every 8.0 fs using the particle mesh Ewald97 algorithm with a 1 Å grid spacing. All energy minimization runs were conducted using a CPU-only version of NAMD v.3.0.1, while NPT production simulations were performed using the GPU-resident NAMD v.3.1 alpha 2 (ref. 90).

IN–CA interaction contact analysis

Residue-level contacts between IN and CA were analysed across all simulation trajectories using custom Tool Command Language scripts in VMD88. For each frame of a simulation trajectory, the coordinates were evaluated to assign contacts between IN and CA residues. Contacts were evaluated using a 3.5 Å distance threshold. Contact occupancies were calculated as the fraction of frames in which a given pair of residues remained within this distance threshold, relative to the total number of frames in the trajectory. A contact with 100% occupancy indicates that two residues remained within 3.5 Å of each other throughout the entire trajectory, while an occupancy of 0% indicates that no contacts were identified at any point. Due to the symmetry of the IN octamer, the four IN–CA contact regions were present in duplicate (one in each IN tetramer). Thus, contact occupancies reported in Extended Data Fig. 8 represent the average across symmetry-equivalent IN–CA contact regions in the IN octamer and across all simulation replicas. In total, over 200,000 frames were analysed to calculate contact occupancies, with each frame representing 20 ps intervals in the simulation.

Virology

Synthetic fragments (IDT) carrying CA and SP1 changes were incorporated into SpeI/ApaI-digested pNLX.Luc.R(-)ΔAvrII DNA98 using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly kit. IN changes were similarly made using AgeI/PflMI-digested plasmid. Plasmid pLR2P-vprIN99 was digested with BamHI and XhoI to incorporate synthetic IBD fragments (LEDGF/p75 residues 347–471) downstream of Vpr. All newly made plasmids were verified by restriction enzyme digestion and whole-plasmid sequencing (Plasmidsaurus). Plasmid DNAs expressing single-round IN mutant luciferase viruses H12N, V165A and D64N/D116N were as previously described20.

HEK293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216), which were used to produce viruses by transfection and also for infection assays, were cultured as described above for Lenti-X HEK293T cells. Cells were confirmed negative for mycoplasma contamination by PCR using PHOENIXDX MYCOPLASMA MIX (Procomcure Biotech, PCCSKU15209). For reverse transcription and infectivity assays, around 106 cells plated the previous day into six-well plates were co-transfected with around 2 µg total DNA consisting of pNLX.Luc(R-)ΔAvrII and vesicular stomatitis virus G envelope expressor (VSV-G) at a 6:1 mass ratio using PolyJet DNA transfection reagent. For Vpr-IBD and Vpr-NG-IN complementation experiments, the mass ratios were 5.1:0.9:1 (pNLX.Luc(R-)ΔAvrII:Vpr-IBD:VSV-G) and 3:1:1 (pNLX.Luc(R-)ΔAvrII:Vpr-mNeonGreen-IN:VSV-G). After 2 days, the supernatants, precleared at 500g for 5 min, were filtered through 0.45-µm filters and treated with 2 U µg−1 Turbo DNase for 1 h at 37 °C to degrade residual plasmid DNA. The concentration of p24 was assessed using an ELISA kit from Advanced Bioscience Laboratories. For immunoblotting and TEM, transfections were scaled up (around 107 cells plated the previous day in 15 cm dishes) to 30 µg total plasmid DNA. The resulting 0.45 µm filtered supernatants were pelleted by ultracentrifugation using a Beckman SW32-Ti rotor at 26,000 rpm for 2 h at 4 °C.

Infections, normalized by p24 to 0.25 pg per cell, were performed with around 105 HEK293T cells per 24-well plate well. At 6 h after infection, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM. At 48 h after infection, cells were collected, washed twice with PBS and lysed using passive lysis buffer as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega). The luciferase activity, assessed as relative light units per µg of total protein in the cell extracts (RLU per μg), was determined as previously described100. Infections for reverse transcription measurements were washed after 1.5 h to remove virus and included dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 20 µM efavirenz to control for potential plasmid carryover from transfection. Genomic DNA was isolated at 8 h after infection and quantitative PCR was performed as previously described101. DNA quantities were normalized by spectrophotometry and reverse transcript levels were normalized to the WT after subtracting Ct values for efavirenz-treated cultures from matched DMSO-treated samples.

For immunoblotting, volume-normalized virus pellets resuspended in protein sample buffer were separated by electrophoresis on Bolt 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes blocked for 1 h at room temperature were probed overnight at 4 °C in 12.5% non-fat dry milk containing a 1:1,000 dilution of mouse anti-CA monoclonal AG3.0 (obtained from the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH and contributed by M.-C. Gauduin) or 1:2,000 dilution of inhouse rabbit anti-IN polyclonal antibodies102. The next day, the membranes were probed with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (goat anti-rabbit, Agilent, P0448, 1:2,000; rabbit anti-mouse, Dako, P0161, 1:4,000), treated with enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents and imaged on the ChemiDoc MP imaging system. The relative intensity of IN signals was normalized to CA signals using ImageJ103.

For TEM, virus pellets were resuspended in 1 ml fixative solution (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.25% paraformaldehyde, 0.03% picric acid, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The preparation and sectioning of fixed virus pellets were performed at the Harvard Medical School Electron Microscopy core facility as previously described104. Sections (50 nm) were imaged at ×20,000 to ×30,000 magnification using the JEOL 1200EX or Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTWIN transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV. Approximately 40 micrographs were recorded per sample, and viruses were manually counted and assigned on the basis of one of seven different phenotypes (Fig. 4d).

Statistics

Individual virus-based experiments (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 4b) had technical duplicate samples and the results are presented as the mean ± s.d. of at least n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analyses, conducted in GraphPad Prism v.10.6.0, compared mutant viral responses with the WT (Fig. 4) or matched sets of Vpr-complemented viruses (Extended Data Fig. 4b) using one-way or two-way ANOVA with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were omitted for samples that lacked n = 3 independent experiments (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Owing to practical constraints, investigators were not blinded to sample identity and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.