India stands at a turning point in its agricultural journey. Its fertilizer subsidy programme, a cornerstone of its food-security strategy, now threatens the sustainability it aims to ensure1. The programme needs reform.

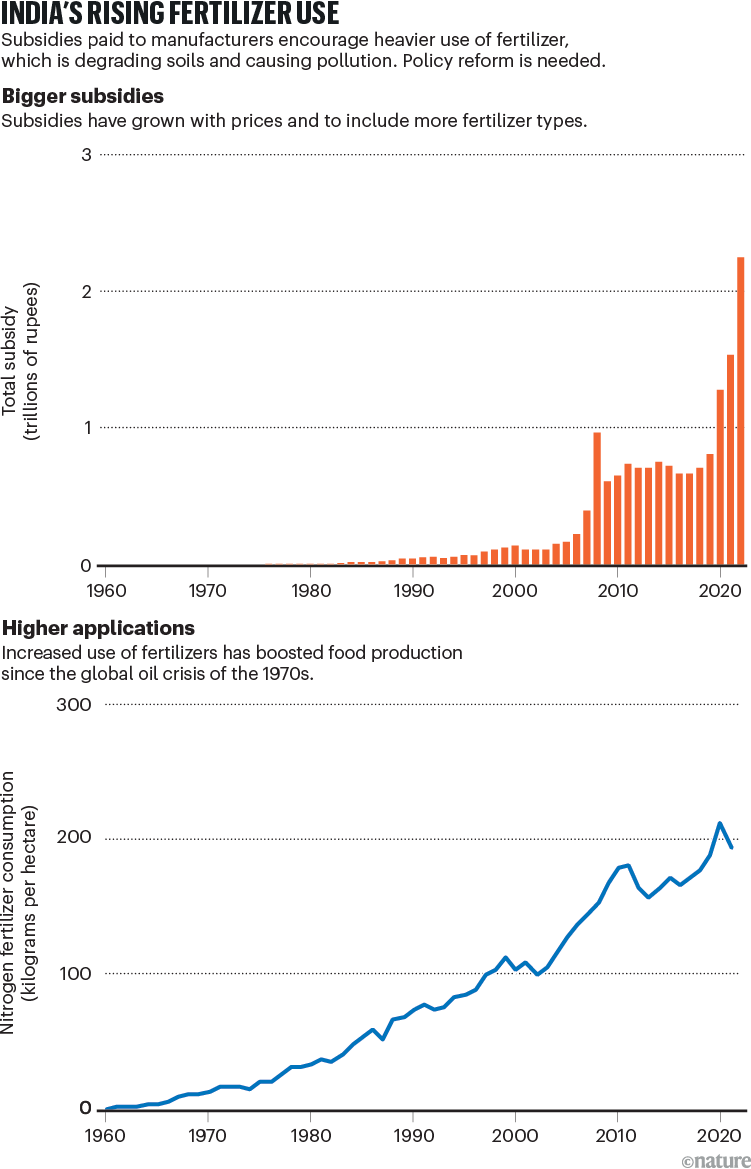

In the current system, the government pays subsidies to fertilizer manufacturers so they don’t need to charge as much for their products. This means that farmers are often unaware of the true cost of urea and other chemical fertilizers, so tend to overuse the products (see ‘India’s rising fertilizer use’). This is resulting in severe soil degradation, water pollution and increased greenhouse-gas emissions2,3. For example, in 2017, overuse of nitrogen-based fertilizers added 57% to the country’s agricultural greenhouse-gas emissions4.

The overuse is also straining the national purse5. For the 2024 fiscal year, India has allocated one-ninth of its total agricultural budget to fertilizer subsidies, almost US$20 billion (1.6 trillion rupees). Yet around $715 million of that spend will be lost: a lot of India’s subsidized urea is diverted to non-agricultural uses (plywood manufacturing and textile processing) or smuggled to neighbouring countries.

Sources: Subsidies: Govt of India/Ref. 5. Applications: FAOSTAT (https://go.nature.com/3NOVNGS)

Compounding these issues, some 70% of Indian farmers apply fertilizers without first testing the soil properly or adhering to nutrient-management recommendations. This is degrading the health of the soil, which could have long-term effects on soil fertility and agricultural productivity6. Excessive fertilizer use in the Indo-Gangetic plains, for instance, has led to soil acidification and reduced crop yields7.

Furthermore, the current system discourages innovation in the fertilizer industry. Manufacturers have little incentive to improve the efficiency of their production processes or develop more environmentally friendly products.

All these problems are widely acknowledged. In 2018, India took a step towards addressing leakages by recording sales of subsidized fertilizers to farmers through point-of-sale devices. Although this has reduced losses, it hasn’t addressed the underlying issues — lack of farmer awareness around soil health, injudicious fertilizer use and low environmental sustainability.

After consultations with several government representatives and researchers in India, here I propose a way to overhaul the existing model for fertilizer subsidies. Transferring subsidies directly to farmers’ bank accounts and linking them to soil-health programmes would empower farmers to make more-informed decisions. Knowing the true costs, they should use less fertilizer. This could reduce fertilizer run-off into water bodies by millions of tonnes and save the government billions of dollars.

A path to sustainability

A series of adjustments would make India’s agricultural system more sustainable (see Figure S1 in Supplementary information). These build on India’s existing digital infrastructure, including the ‘Aadhaar’ identification system and the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana financial inclusion programme. Aadhaar is a 12-digit unique identity number issued to all Indian residents and based on their biometric and demographic data. The Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana aims to ensure that every household in India has access to bank accounts and other financial services.

Direct transfer of subsidies to farmers’ bank accounts. If farmers have control over the subsidy funds, they would be incentivized to optimize their fertilizer use because they would experience the financial impact of their decisions directly. If they use less fertilizer than expected, they can keep any remaining subsidy for other agricultural inputs or personal use.

India budget: Modi bets big on nuclear energy and space

Payments would be scaled on the basis of landholding size, crop type and local soil conditions, ensuring that farmers receive subsidies only for the amount of fertilizer they would need if they farmed sustainably. For example, a farmer with a two-hectare plot growing rice in a region with nitrogen-deficient soil might receive a higher subsidy than would a farmer with the same size plot growing lentils in an area with naturally nitrogen-rich soil.

One study8 suggests that optimizing nitrogen use in Indian agriculture could reduce nitrous oxide emissions by at least 30%. This reduction, combined with the potential for increased carbon sequestration in healthier soils, could make a substantial contribution to India’s commitments under the Paris climate agreement.

Direct transfers would also reduce leakages in the subsidy system by up to 40%, according to pilot studies9. This could potentially save the government billions of dollars annually, which could then be reinvested in farmers or in the betterment of farmers through agricultural research and rural development. And by making sure that all farmers have bank accounts, the system could accelerate financial inclusion in rural areas, opening up opportunities for credit access and digital financial services.

Market-driven pricing of fertilizers. A dynamic pricing mechanism, with a subsidy that is adjusted according to market prices, environmental conditions and crop-specific needs, would ensure that the subsidy remains effective while promoting sustainable practices. For instance, during periods of high market prices, the subsidy could be increased to maintain affordability for farmers. Conversely, in regions experiencing good rainfall and soil conditions, the rate might be lowered, because less fertilizer would be needed.

Improved soil-management practices would help to ensure sustainable production of coffee berries in India.Credit: Abhishek Chinnappa/Getty

To illustrate: if the market price of urea rises from 5,000 to 6,000 rupees per tonne, the government could increase the subsidy from 90% to 95% of the price to keep the farmer’s costs relatively stable. Similarly, in a drought-prone area during a good monsoon year, the subsidy might be reduced from 50% to 40%, encouraging farmers to rely more on natural soil fertility.

This mechanism would also encourage fertilizer companies to develop more efficient and environmentally friendly products, potentially positioning India as a global leader in sustainable agricultural inputs. Although there might be initial cost increases as companies invest in research and development, the long-term benefits of more-efficient fertilizer use could lead to overall cost reductions for farmers.

Integration of subsidies with soil health data. Subsidy payments could be linked to a scheme known as the Soil Health Card. Run by the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, this scheme provides farmers with detailed information about their soil’s nutrient status and recommends appropriate doses of fertilizers. It currently covers all 150 million farm holdings in India.

Genetic modification can improve crop yields — but stop overselling it

When a farmer applies for a subsidy, the system would automatically check their Soil Health Card data. By combining these data with information about the farmer’s crop plans and local climate conditions, the system would calculate the optimal fertilizer requirement. The subsidy amount would then be tailored to this requirement, effectively discouraging overuse.

Data on fertilizer-use patterns could also be used to inform policies because they would be obtained through the point-of-sale devices used for fertilizer purchases and linked to the farmer’s Aadhaar identification number. The digital infrastructure required would enable more targeted agricultural policies and research initiatives, catalysing a broader shift towards precision agriculture in India.

A digital platform for managing subsidies and advising farmers. This platform would serve as a one-stop solution for farmers, integrating subsidy management, soil health information and agricultural advisory services. It would be accessed through smartphones or through local community service centres. It would include a subsidy calculator that could show farmers the money they would receive on the basis of their land, crops and soil health data, as well as real-time market prices for fertilizers and other agricultural inputs. It could also provide personalized crop and fertilizer recommendations according to the current soil health and local weather conditions. Educational resources on sustainable farming practices could be shared. A help desk for technical support and grievance redressal should be included.

I propose integrating this platform with government initiatives such as crop insurance (Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana) and minimum support price schemes that guarantee payments to farmers for certain crops (called PM-KISAN), creating a holistic support system for farmers.

Incentives for adopting sustainable farming practices. The digital platform could incorporate principles of behavioural economics, using ‘nudges’ to help farmers to make sustainable choices. For example, farmers who opt for organic fertilizers or practise crop rotation might receive extra subsidy points or priority in other government schemes. Recognition and awards might be given for ‘model farmers’ who demonstrate best practices.

These incentives would be customized for different agro-climatic zones. For instance, in water-stressed regions, there might be extra incentives for adopting water-efficient farming methods along with optimal fertilizer use.

Addressing challenges

The proposed model offers a path towards sustainable intensification of agriculture, aligning with India’s commitments under the Paris agreement and to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. However, there are challenges to its implementation, requiring a comprehensive approach.

One hurdle is the lack of complete and robust land-ownership records, which has impeded other targeted subsidy schemes in India. To tackle this, I advocate for a phased implementation, starting with regions that have more reliable records (such as Punjab state) and accelerating land-record digitization.

A parched paddy field near Ahmedabad, India.Credit: Amit Dave/Reuters

In the long run, satellite imagery could be used to verify land use and crop patterns, while blockchain technology could ensure secure and transparent record-keeping of land ownership and subsidy disbursements. Monitoring other crop input purchases or sales of products would confirm eligibility, too.

Farmer adaptation is crucial, and I propose extensive awareness campaigns, hands-on training and a user-friendly mobile app with voice-based instructions in local languages. To include tenant farmers, I propose a registration system with provisions for tenancy agreements, verified by local government bodies.

Another challenge is the readiness of the nation’s infrastructure, particularly in rural areas, which have limited Internet connectivity and banking services. To mitigate this, I suggest collaborating with telecommunications companies through public–private partnerships, establishing mobile banking units and digital service centres in remote areas, and developing offline modes of subsidy disbursement with periodic synchronization. Recognizing the digital literacy gap, I propose a network of local support centres to assist farmers with registration, subsidy claims and troubleshooting.

M. S. Swaminathan (1925–2023), leader of India’s ‘green revolution’

Data privacy and security concerns can be addressed through robust protection measures, including end-to-end encryption and strict access controls, along with clear, transparent data-use policies. To prevent misuse, biometric verification, periodic audits and machine-learning algorithms can detect fraudulent activity.

Financial literacy and inclusion challenges can be tackled through education programmes, partnerships with local financial institutions and accelerated efforts to open bank accounts for farmers who do not already have them.

To ensure timely disbursement, I propose streamlining the subsidy calculation and disbursement process. This would involve automating the calculation of subsidy amounts according to real-time data inputs, including soil health, crop type and market prices. The disbursement process could be expedited by using blockchain technology to ensure transparent and nearly instantaneous transfers. For example, smart contracts on a blockchain network could automatically trigger subsidy payments when specific conditions (such as verified fertilizer purchases) are met.

Advance subsidy credits could also be offered. As with a pre-approved credit line, farmers could be allocated a certain amount of subsidy in advance according to their historical use patterns and current cropping plans. They could draw on this credit as needed, with the final subsidy amount being reconciled at the end of the season on the basis of actual use.

Biases in ‘sustainable finance’ metrics could hinder lending to those that need it most

To address market volatility concerns in a deregulated fertilizer market, I recommend implementing price monitoring mechanisms, considering using price ceilings during the transition and encouraging long-term contracts between farmer cooperatives and manufacturers.

To tackle potential industry resistance, I suggest a gradual transition period and efforts to highlight the incentives for companies to innovate, including benefits such as real-time transactions and improved supply chains that could overcome current long wait times for payments.

To allay food-security concerns and ensure long-term success, I propose careful monitoring of agricultural output during the transition, with provisions to adjust the model if necessary. That should be supported by a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework that uses remote-sensing technologies, soil health cards and crop-yield data.

This multi-faceted approach aims to address the complex challenges associated with transforming India’s fertilizer subsidy programme, paving the way for a more sustainable and efficient agricultural sector.

The path forwards

To implement this transformative model, a series of coordinated actions across government bodies and institutions are needed. The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare can spearhead a pilot programme in selected districts, chosen to represent diverse agro-climatic zones and land ownership patterns. This pilot should span at least two agricultural seasons, to capture seasonal variations and enable iterative improvements.

In Asia, alternative proteins are the new clean energy

Concurrently, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology must fast-track the development of a robust digital platform for subsidy disbursement, seamlessly integrating it into PM-KISAN and other existing schemes (as happened with PM-KISAN, which provides income support to small and marginal farmers, and the Soil Health Card). The Department of Fertilizers should engage in collaborative dialogue with industry stakeholders to chart a roadmap for transitioning to a market-driven pricing model, incorporating incentives for the development of innovative, sustainable fertilizer products.

State governments, with support from the central government, need to accelerate efforts to digitize land records. Agricultural universities and research institutions should be tasked with conducting extensive studies on this system’s impact on soil health, crop yields and farmer incomes, providing crucial data-driven insights to help refine the policies.

The Ministry of Finance must allocate funds to farmer-education programmes. And, for oversight, a task force should be established to manage implementation efforts across government departments.

This coherent multi-pronged approach, involving key stakeholders at various levels, is essential for the successful transformation of India’s fertilizer subsidy programme. The path to implementing such a model will undoubtedly be complex, requiring careful planning and wide engagement. However, the potential rewards — in terms of improved environmental sustainability, economic efficiency and farmer welfare — make it not just desirable, but necessary.