Neutrophils (artificially coloured) can extrude a sludgy substance in a ring around a puncture wound. Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Immune cells in the skin ‘cauterize’ open wounds and create ‘band-aids’ to prevent the spread of harmful bacteria and foreign molecules from injury sites, finds a study1 in mice.

The works shows that white blood cells called neutrophils form gooey, protein-rich rings around sites where the skin has been breached. These rings trap pathogens, ensuring that they don’t penetrate into deeper tissues.

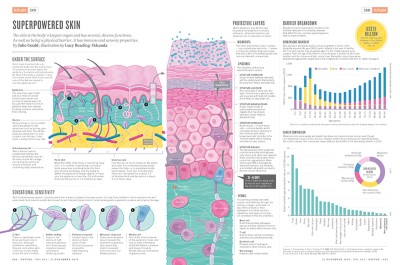

Superpowered skin

Scientists have long known that neutrophils wage chemical warfare by releasing toxins to kill invading microorganisms. But the new work, published today in Nature, reveals “an additional role for neutrophils here that we had not appreciated”, says Niki Moutsopoulos, a clinical immunologist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, who was not involved with the study. The findings show that neutrophils aid in wound healing — and are not just immune warriors, she adds.

The study also highlights a new defence tactic that the immune system deploys to protect the body beyond destroying germs. To the authors’ surprise, neutrophils “prevent conflict before they go into this biochemical war. They build the structures to separate self from non-self, to keep pathogens [away],” says study co-author Andrés Hidalgo, an immunologist at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Multi-talented immune cells

Neutrophils are known to poison invading microbes and to swallow them. But these strategies cause “collateral damage” to the body by killing healthy bystander cells, Hidalgo says.

The skin’s ‘surprise’ power: it has its very own immune system

To investigate whether neutrophils have another trick up their sleeves, the researchers examined samples of mouse skin, lungs and gut ― organs that have contact with the external environment and are lined with protective layers to help ward off pathogens and foreign substances. Hidalgo and his colleagues found that a high percentage of neutrophils in these tissues produce collagen and other proteins that are important for forming ‘extracellular matrix’, a scaffolding that surrounds cells and gives tissues structure. By contrast, neutrophils in blood did not release collagen.