Jingming Cai says he deliberately shaped his PhD’s focus to prepare for future applicationsCredit: Cavan Images/Getty

After completing my PhD in engineering in September 2018, I set out to navigate the world of early-career fellowships — a path that taught me as much about resilience and strategy as it did about research.

After experiencing two rejections, rewriting my proposals and learning from every round of feedback, I have secured three major awards over the past five years: a Humboldt Research Fellowship in Germany, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship (MSCA-PF) from the European Union and a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) from the Australian Research Council. These totalled around US$600,000 in funding, which supported my early-stage research across multiple countries. Now, I’m an associate professor at the School of Civil Engineering at Southeast University in Nanjing, China, where I conduct research on energy technologies for buildings.

All three fellowships are highly competitive — for instance, the success rates for the MSCA-PF and DECRA were both around 15% when I applied. Each application process pushed me to reflect not only on how to write a convincing proposal, but also on who I am as a researcher, what kind of work I want to do and how to communicate that to others. Here are some lessons that I learnt the hard way — and that might help others going through the same process.

Start preparing before you finish your PhD

The best applications don’t start with a call for proposals — they start months, and sometimes years, earlier. In the final year of my PhD, I became aware of several major international fellowships for early-career researchers. With these opportunities in mind, I deliberately shaped my work to strengthen my CV and prepare for future applications. I focused on building a clear research identity: publishing in the niche but promising field of thermoelectric materials for buildings, and collaborating internationally. This helped to demonstrate that I could work across borders. These shifts weren’t always straightforward — I had to take care that my activities remained aligned with my doctoral objectives without compromising the integrity of my research.

For example, I actively took part in international academic conferences on emerging energy technologies, even though they were not entirely relevant to my core research area. These experiences later helped me to identify institutions that would be suitable hosts if I attracted funding, and to collect strong letters of recommendation.

I also learnt the importance of being flexible with my research direction. Early on I focused entirely on structural design in buildings, but I later realized that combining structural design with energy research was better suited to my strengths. It also aligned more closely with emerging needs in the field, and so would be relevant to more calls for grant funding. I think similar opportunities exist in the natural sciences, particularly because many areas are now integrating with digital tools such as artificial intelligence and the use of big data, so expertise in those areas is transferable.

Choosing a research direction that plays to your strengths and can respond to developments and demands in the field can make a real difference. I attended a number of interdisciplinary talks, which gave me a broad view of where the field was heading. I decided to shape my direction accordingly, while keeping my own interests in mind. I tried to be as independent as I could in choosing a research direction: after all, the grants I was applying for were specifically to build my own research direction.

Use early applications to practise and build confidence

I submitted my first MSCA-PF application shortly after finishing my PhD — and was rejected. The core proposal was around 15 pages long and required detailed planning of research content, collaborations and implementation. I had only three months to prepare it, and I underestimated the importance of a well-structured narrative. As a result, the submission lacked coherence and clarity, and didn’t address the scientific questions in enough depth. For example, my methodology did not include enough detail.

I asked for feedback and started again. I rewrote the proposal from scratch: clarified my role in the project, restructured the scientific goals so that they were more focused, with concrete and feasible methods, and worked closely with my collaborators and host institution. The second time around, the proposal scored 98.8 out of 100 and was awarded €189,000 (US$220,000). I used this to start my work on building energy technologies, where I made advances in the field of thermoelectric devices. My colleagues and I developed the most energy-efficient building thermoelectric module known so far, with the potential to convert urban waste heat into electricity and help to mitigate the growing challenges of the urban heat-island effect and energy crisis.

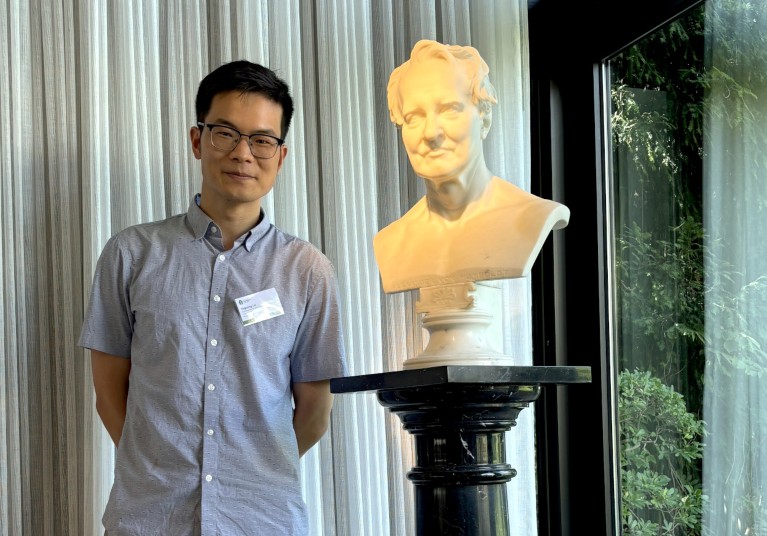

Jingming Cai learned from repeated rejection to win some big time fellowships.Credit: Jingming Cai

For those starting out, I recommend applying to fellowships with simpler formats and flexible timelines — such as those offered by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science or the Humboldt Foundation in Germany. These programmes have a more streamlined application process, focusing on the applicant’s potential and research idea, rather than requiring very detailed project planning and implementation, as the MSCA-PF does. The fellowships are highly respected and are excellent practice for applying to more complex programmes, such as European Research Council funding competitions.

Tell a story — don’t just give a technical plan

The biggest mistake I made early on was treating a fellowship application like a journal submission. My first MSCA-PF draft was packed with bullet points, dense data tables and technical language. But I learnt that reviewers aren’t just evaluating scientific merit — they’re also looking for alignment with their goals, potential to become an independent researcher and a clear narrative. And, of course, how the proposed work would contribute to solving any specific scientific or societal challenges that the fellowship aims to support.

What made the difference in my revised application was learning how to tell a compelling story: who I was, what I had done, what gap I saw in the field and how this project, in this environment, would help me to grow. I included a tailored training plan, showed how the fellowship would support my long-term goals and outlined the societal relevance of the work.

I followed a simple structure:

Background. Introduce the project using a narrative that leads from ‘everybody knows’ to ‘nobody knows’ — start with widely understood context, then narrow down to the specific research gap.

Challenge. Describe the technical bottleneck and explain why this project is needed to overcome it.

Innovation. Explain what makes the idea original and how it differs from existing approaches.

Implementation. Lay out a detailed and feasible plan to ensure timely and effective delivery of the project.

Impact. Clarify the scientific and socio-economic benefits of the project.

This breakdown made it easier for reviewers to follow the logic and understand the value of each component. I avoided jargon and assumed the reviewers were smart scientists, but not necessarily experts in my subfield.