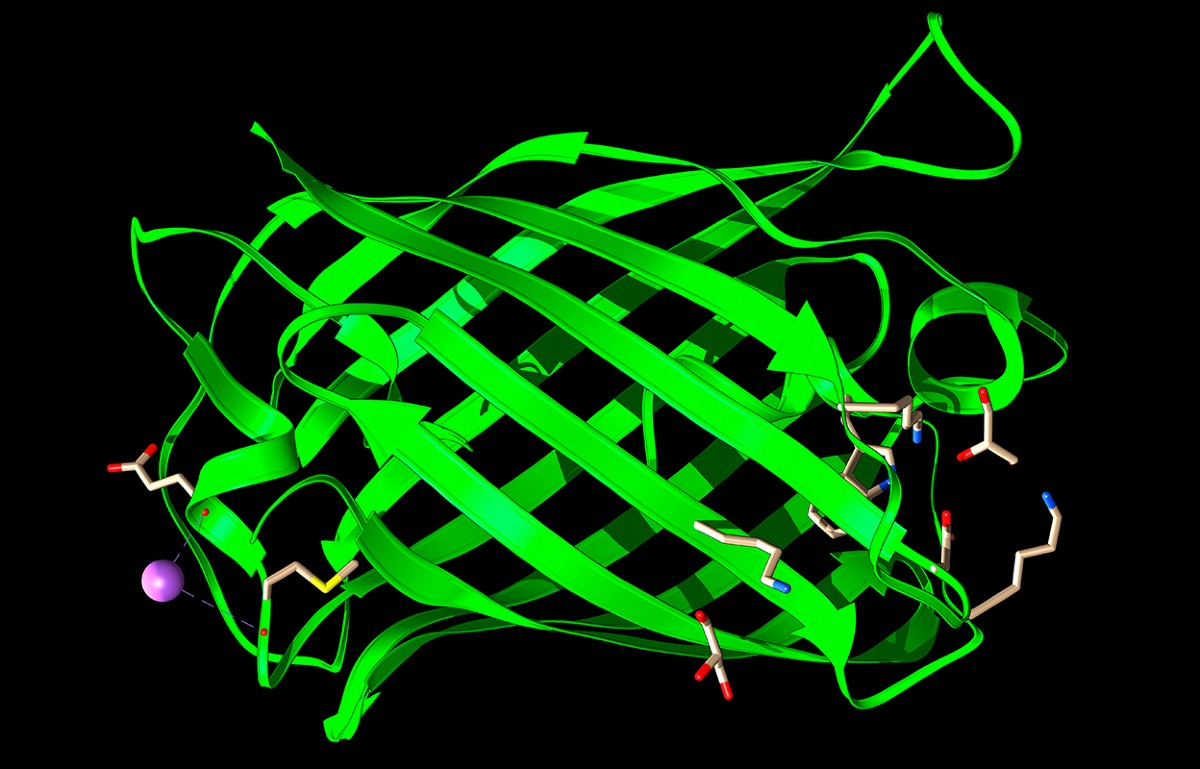

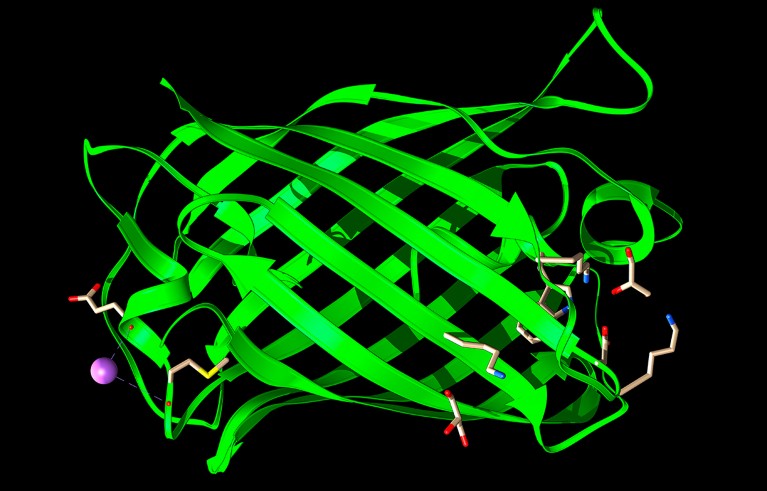

Researchers have used AI models to design working green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) with text instructions.Credit: Laguna Design/Science Photo Library

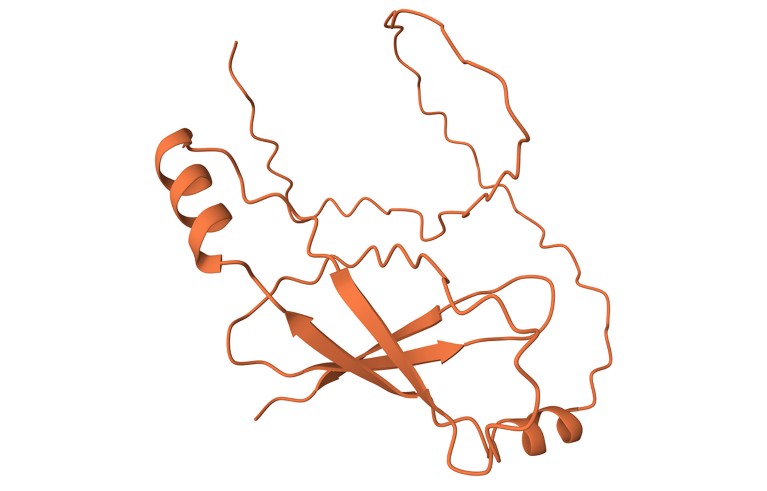

I recently used AI to design an awful protein. Following step-by-step instructions, I made a rudimentary protein language model (PLM) — an artificial intelligence (AI) tool that churns out protein sequences instead of words. With a couple of lines of copied-and-pasted code, I asked the model to dream up a short sequence of amino acids.

What’s next for AlphaFold and the AI protein-folding revolution

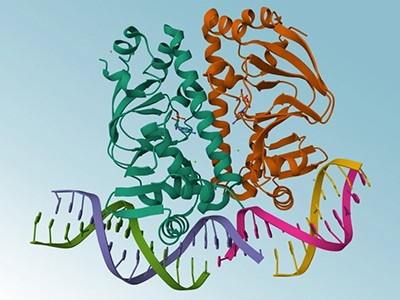

I didn’t know how bad my protein was until I asked AlphaFold, Google DeepMind’s protein-structure predictor, what it looked like. The predicted structure had helices, loops and other realistic elements. But AlphaFold had very low confidence in its prediction — a sign that my molecule probably couldn’t be made in cells in the laboratory, let alone do anything useful.

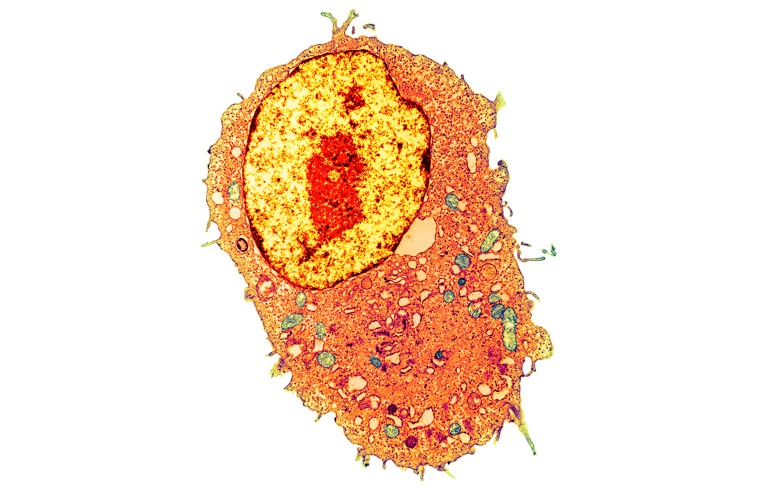

Now, dabblers in computational biology, such as myself, have fresh hope. Scientists are developing a new generation of biological AI tools that take instructions in plain language and turn them into proteins and other molecules, including potential drugs. The models also allow researchers to ‘talk’ to cells in ordinary English to decipher their inner workings and glean other biological insights.

It is the latest turn of events in the bio-AI revolution that is transforming fields such as protein design and structural biology. PLMs and other AI tools enable scientists to design molecules such as enzymes and antibodies with relative ease. But getting the most out of these tools typically requires considerable expertise.

AI-generated images threaten science — here’s how researchers hope to spot them

Models that allow users to interrogate biology using plain text could lower the barrier to joining the bio-AI revolution, say scientists. These AIs also have the potential to enable greater control over the resulting designs and other outputs.

“It would be useful to be able to specify precisely what we want, and have a protein be designed with those features,” says Mohammed AlQuraishi, a computational biologist at Columbia University in New York City.

Text-to-protein

Last month, a team led by Fajie Yuan, a machine-learning scientist at Westlake University in Hangzhou, China, showed that a text-to-protein model his team developed can design functional proteins, including lab-tested enzymes and fluorescent proteins, that are original in their designs and not similar to existing molecules. “We are the first to design a functional enzyme using only text,” Yuan says. “It’s just like science fiction.”

‘An awful protein’: reporter Ewen Callaway created a protein language model (PLM) and used basic code instructions to generate this protein.Credit: Google DeepMind/EMBL-EBI (CC-BY-4.0)

The model, called Pinal, is one of several protein-design AIs that can be directed with ordinary language — as opposed to a protein sequence or the structure-guided specifications typical of most such AIs.

But it’s early days for these bio-AI models, says Anthony Gitter, a computational biologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “I see it as a high-risk, high-reward area,” he says.

How to speak molecule

Teaching biological AI models to communicate in English (or any language) typically involves exposing them to text descriptions of biological data. Yuan’s team trained Pinal using short descriptions of the structures, functions and other characteristics of 1.7 billion proteins. After some extra training, the model could take a prompt and churn out hundreds of sequence designs1. The model has a web interface, but is not openly accessible.

AI protein-prediction tool AlphaFold3 is now more open

One prompt that the researchers used was ‘Please design a protein that is an alcohol dehydrogenase’, referring to an alcohol-metabolizing enzyme. Yuan and his colleagues then used other computational tools to identify the most promising designs and, working with a biologist collaborator, tested their enzymatic activity.

Two of the eight alcohol dehydrogenase designs successfully catalysed the breakdown of alcohol, albeit far less efficiently than natural enzymes. Yuan says his team has also designed working green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) and plastic-degrading enzymes, all dissimilar in sequence to natural examples.

Several other teams have developed similar AI models, including one called ESM-3 that can be prompted with keywords, as well as with protein sequences and structures. A start-up firm called 310.ai has developed a proprietary tool called MP4 that designed a slew of proteins from text inputs2, including several that, in the lab, can bind to the cellular energy source ATP. The company is using the model to design proteins that act like GLP-1 drugs, the blockbuster obesity treatments, says its vice-president of discovery Timothy Riley.

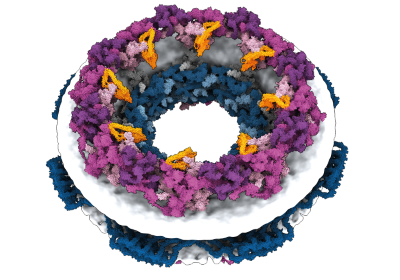

Talk to your cells: AI models are enabling scientists to ‘speak’ to cells using ordinary language.Credit: Dr Gopal Murti/Science Photo Library

One challenge for models such as 310.ai’s is coming up with the right text instructions for an AI to follow, says company co-founder Kathy Wei, although LLMs can help to craft successful prompts. She likens it to the early days of image-generating AIs such as Dall-E: some prompts were more fruitful than others, and the models’ struggles to depict human hands, for example, were often a giveaway. Instead of odd-looking hands, MP4 can sometimes spew out proteins with repetitive sequences, says Wei.