Illustration: David Parkins

The advice

Nature’s Careers team reached out to two researchers and an employment lawyer for advice.

“This story has all the hallmarks of uncompensated labour done by faculty” members, says Hava Rachel Gordon, a sociologist at the University of Denver in Colorado. “It happens all the time, whether they belong to an institution or are doing work for another institution.”

Gordon notes that academics often view themselves as passionate scholars, scientists and teachers. “We don’t often think of ourselves as workers,” she says. “And the problem is, then we are easily taken advantage of.”

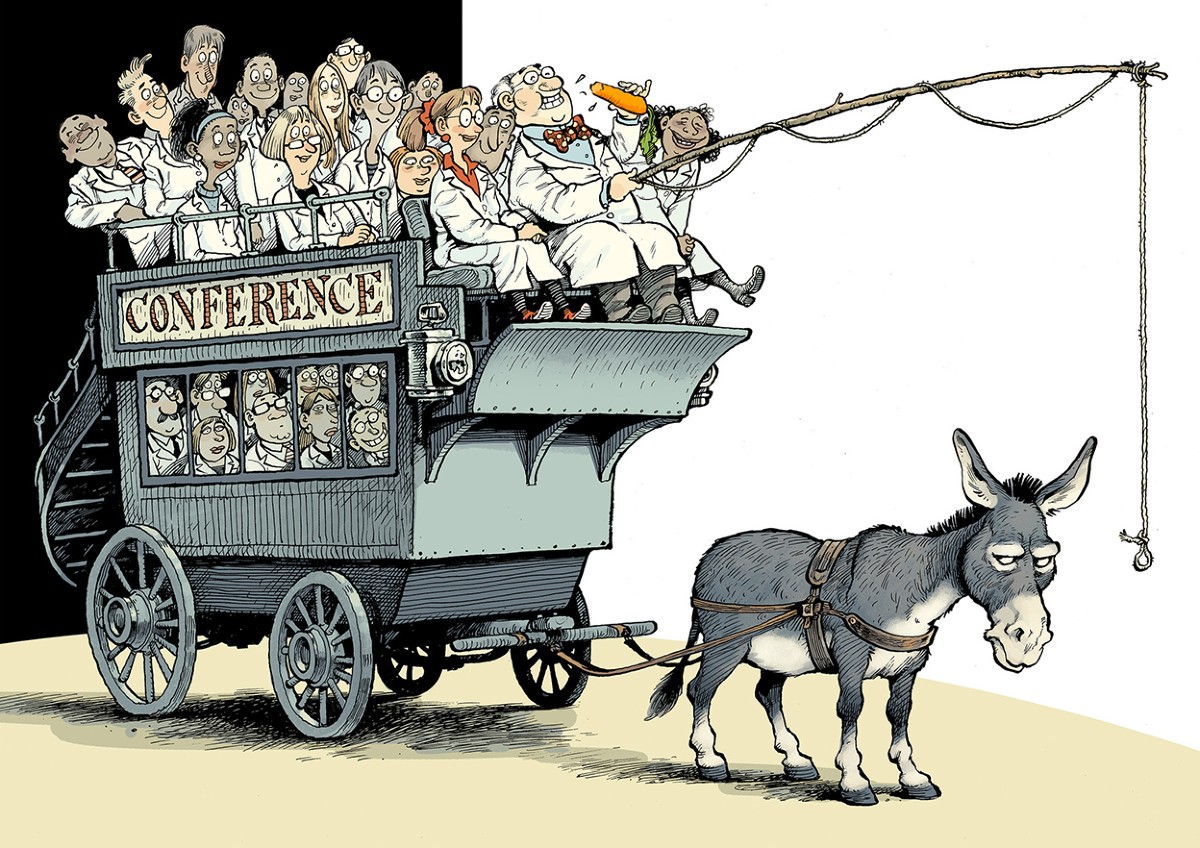

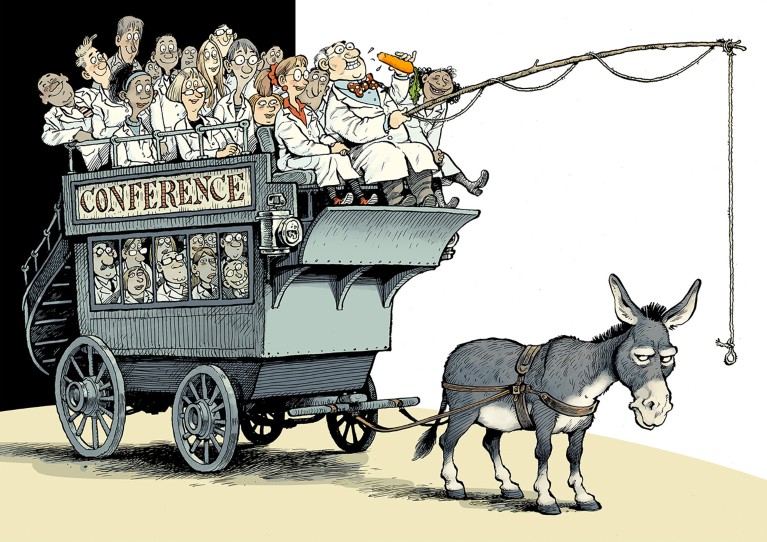

All the sources noted that one of the challenges of working in academia is defining what the job itself entails. Along with research, teaching and service, many faculty members engage in mentorship, public outreach, administrative work and other tasks. Some of this work is paid, but compensation for other labour, such as reviewing grant proposals or giving conference presentations, might take the form of increased stature in the field or enhanced job prospects.

However, there is also uncompensated or invisible labour, which is neither rewarded nor recognized in merit reviews1.

Studies have found that women and faculty members of colour spend more time on campus service, diversity-related service, student advising and teaching than do their male and white peers, and this can delay career progression by taking time away from research2,3.

The time tax put on scientists of colour

“A lot of these requests are done informally without contracts, sometimes without even a paper trail. We call it a hallway ask,” says Gordon, referring to a 2018 article by KerryAnn O’Meara, a higher-education researcher at Columbia University in New York City, describing how the most agreeable and productive faculty members are often stopped in corridors and asked to take on various service tasks.

Gordon emphasizes that she understands why the distressed scientist agreed to organize this conference, but notes that it’s difficult to demand payment without a contract in place.

“I think the real problem here is that the parties didn’t make an arrangement ahead of time,” says David Belfort, founding partner of the employment-law firm Bennett & Belfort in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “The scientist needs to put their foot down and tell the institution that they’re willing to do the work, but that it needs to be compensated, because they can’t work for free for two years with the expectation that they’re going to get a job offer out of it.”

Belfort acknowledges that the situation is tricky, given that conference organizing is often voluntary, ancillary work conducted by individuals who are paid, full-time employees at universities. “The odd thing here is that if they had received an offer of a position at this institution, they likely would be content. However, there is no quid pro quo — the institution is not required to offer any role going forward — but they may be entitled to back pay for their work.” For instance, if the distressed scientist had carried out this work in certain US jurisdictions, Belfort says, they could claim a violation of state-minimum-wage laws.