Many universities once admitted only male students — and traditions and values from that era still prevail, says Nicole Bedera.Credit: Bettmann/Getty

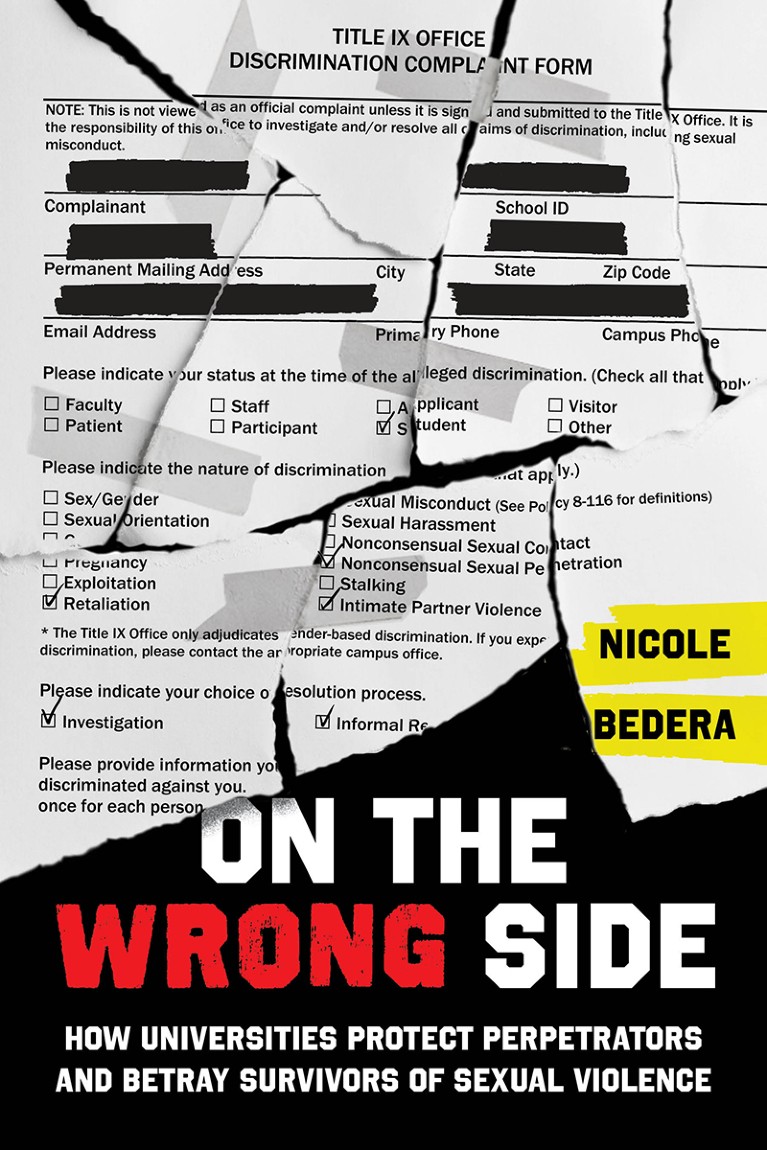

Nicole Bedera spent the 2018–19 academic year investigating how a US university handled allegations of sexual harassment and violence. Her resulting book, On the Wrong Side: How Universities Protect Perpetrators and Betray Survivors of Sexual Violence, was published last year.

Bedera’s investigation was based on interviews with 24 administrators and 45 perpetrators and survivors at the university, which she does not name. She also reviewed more than 700 documents, including media reports and Instagram posts.

Freedom and safety in science

Her research painted a picture of an institution that felt threatened by complaints about gender-based violence, says Bedera. Male perpetrators’ education was routinely prioritized over that of female victims, leaving the impression that sexual-violence complaints were not taken seriously, she adds.

Many higher-education institutions in the United States continue to rely on traditions and values that pre-date the admission of female students. Women continue to feel excluded.

A sociologist and sexual-violence researcher based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Bedera co-founded Beyond Compliance Consulting in 2023. The company’s work includes helping organizations to develop anti-violence strategic plans.

Nicole Bedera is a sociologist who studies sexual violence and responses to it.

How did you become interested in researching sexual violence on campus?

It dates back to 2010, when I started my bachelor’s degree in sociology at a US liberal-arts college. I thought feminism had been won. That was what I’d been taught growing up in Nevada at the height of the 1990s ‘girl power’ era.

On our very first day, we were told that there had not been a rape on my campus in ten years.

But some of my friends were later sexually assaulted, and were left with the impression that their continued presence in campus accommodation would somehow disturb their roommates. I felt that was a horrible message.

I began volunteering for a rape crisis centre, and this led to me working as a victim advocate in hospitals. In that role, I got a lot of questions from survivors that there just weren’t really very clear answers to. One of these was why everything got worse, instead of better, after they reported their assault.

For example, in the United States, if you’re sexually assaulted, the place where you start the criminal-justice process is a hospital, for an examination. That is the exact opposite of what a sexual-assault survivor would want — being stripped naked and examined from head to toe.

We had things that we said as advocates, but I wanted to give a scientific answer to their questions.

The conventional approach and that of a lot of the academic literature at the time was to say that they’d done something risky, that they’d done something wrong, that they’d put themselves in that situation. But that was hard for me to believe, and it wasn’t something I wanted to repeat.

And so that’s how I came into my research interest and my PhD at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, which focused on how organizations shape the experience of college sexual assault.

How did your advocacy experience inform your work as a social scientist?

What I learnt as an advocate that was most useful as a scientist was to make space for the full expression of emotion. A lot of the time, whether it’s in the hospitals or in a research interview, victims will act differently than you’ve been taught to expect.

In the cultural stereotypes, people think interviews will be very sad, and people will cry through all of them. That’s not true. A lot of them are very funny — some people cope through humour. People also cope through anger, as well as sadness.

When you make room for that full expression in each interview, you often see all those emotions, and you get a much more nuanced account of what the person has experienced and a more honest story. It means people don’t feel like they have to be ‘the perfect victim’.

How did you maintain scientific rigour when you were interviewing survivors?

Your role as an advocate is to be there, be compassionate, be empathetic, hear what they’re saying, really listen, but also keep some distance because they might handle things differently than you.

Those skills are really useful when working as a scientist, too. When you are interviewing people, you don’t want to have a big emotional reaction. You don’t want them to know your opinion about what they’ve experienced, or how they decided to handle it. Those things are really not relevant to the research.

What struck you most during the research for your book?

Victims of sexual assault shouldn’t be made to feel it’s their fault, and that’s motivated my work.

One of the most upsetting parts of my research was the way administrators talked about handling sexual-violence complaints. There were a lot of cases of sexual harassment, for instance, where the perpetrator would confess to what they had done. And even in those cases, administrators would say, “We don’t want to have to deal with this, we don’t think it’s that big a deal.”

Bedera’s book On the Wrong Side explores responses to complaints of sexual violence at a US university.

One of them said something that immediately stuck in my head: “I just feel like we are regulating student dating, and we’re not interested in doing that.”

They were saying they didn’t enjoy making people accountable for violating the university’s own code of conduct, and that as much as they could, they tried to look for loopholes and ways to avoid investigating or making a meaningful sanction.

One of the consistent themes was that schools prioritized “neutrality”, which meant treating victims and perpetrators exactly the same. For example, the university was sending no-contact directives to perpetrators, but also to the victims, treating them equally, literally as Party 1 and Party 2. Neither were allowed to contact each other or ask others to contact the other person on their behalf. They weren’t permitted to talk about each other to anyone else or share space with each other. But enforcement was fuzzy — for example, they were allowed to take classes together or be in the library at the same time.