Erin Spear (centre) teaches interns how to identify plant diseases.Credit: Javier Ballesteros

Internships provide opportunities for early-career scientists to apply their academic knowledge, gain workplace experience and develop the soft skills necessary for successful careers. Although these programmes vary extensively in terms of their target audience, host organization, duration and structure, many science internships are geared towards undergraduate students who are eager to learn about life in research.

When internship programmes are run well, students learn how to conduct experiments, grow their professional networks and present their research. But if students don’t receive proper financial support or academic guidance, internships can be stressful experiences.

Nature spoke to five researchers about what they think it takes to run a successful science internship programme.

CAROLINE PALAVICINO-MAGGI: Keep the spark for science alive

Neurobiologist at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston Massachusetts.

Undergraduate education is a crucial period in a person’s life and internships can have a big influence on career direction. When I take on interns, my goal is to keep their curiosity for science alive. I want to help them to see the genuine fun and beauty in the work that we do.

I set the tone in my laboratory by emphasizing that there’s no pressure here. Mistakes are completely acceptable, you just need to tell someone when something goes wrong. Then we can talk about it and work out whether to try to salvage the experiment or redo it. I encourage my lab members to be kind, respectful and mindful of one another. I don’t tolerate any toxicity, from shouting to being passive aggressive — those are things that make people leave science.

Collection: Careers toolkit

All of my interns are paid or receive course credit for their work. I pair them with graduate students and postdocs on various research projects because both parties benefit from this arrangement. To find the right fit, I interview potential interns and ask about their research interests and goals for their internship. Then I pair them with patient, approachable mentors who have similar interests. My lab explores the neurological basis of aggression in fruit flies. One recent intern project was to use automated software to characterize behaviour in flies. I have a wonderful lab group, because I prioritize hiring people with good hearts and integrity, as well as those with impressive CVs.

Instead of measuring success by whether an intern has learnt technical skills or contributed to a research project, I focus on whether they felt comfortable in my lab. Diverse representation creates a more inclusive and impactful scientific community, benefiting both research and society. A lot of my past interns have told me that they can relate to my background and who I am. I speak Spanish with some of my interns and I give my lab members time off for cultural holidays such as Lunar New Year, Diwali and Eid. Cultivating a sense of belonging and being part of a healthy environment are essential for interns who are testing the waters to see if science is right for them.

RAJENDRA KARKI: Communication benefits everyone

Immunologist at Seoul National University in South Korea.

Rajendra Karki interviews interns to make sure they are a good fit for his lab.Credit: KAOS Science

Interns bring diverse perspectives, backgrounds and skill sets to the lab, enriching the research environment and leading to innovative ideas and solutions. For instance, one project in my lab involved analysing cell-death mechanisms in various liver diseases, but none of our team members had expertise in bioinformatics. Fortunately, one of our interns had the background we needed and was able to step in. Another intern came up with a plan to purchase lab supplies from local stores rather than scientific vendors, which resulted in significant cost savings.

Day-to-day, interns also provide essential support to our researchers, helping to efficiently advance projects. I currently have five interns in my lab. Most of them help graduate students with their projects, but others who spend six months or longer as an intern often have independent projects related to my research programme to study the molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets of infectious and inflammatory diseases, such as colitis and colon cancer.

Most of our undergraduate interns are paid by their institute’s internship programmes, which means they do not receive further payment from us. However, for those who have completed their undergraduate studies and are seeking hands-on experience before pursuing postgraduate studies, the lab offers some financial compensation through its grants. This allows the lab to support the professional development of interns while benefiting from their contributions to its research.

Before I take on an intern, I conduct in-person or virtual interviews to discuss their goals, interest in inflammation, time availability and what they expect from me. If they’re a good fit, I reach out to the graduate students to ask whether they need help with their projects and to discuss the pros and cons of mentoring an intern.

I also invite guest speakers to the lab and encourage the interns to meet with them individually. Many students are anxious about talking to more-senior researchers, but I tell them that they don’t need to discuss science. They can just ask the speaker about where they’re from and what they like to do outside the lab. Small talk can help interns improve their communication skills and grow their networks.

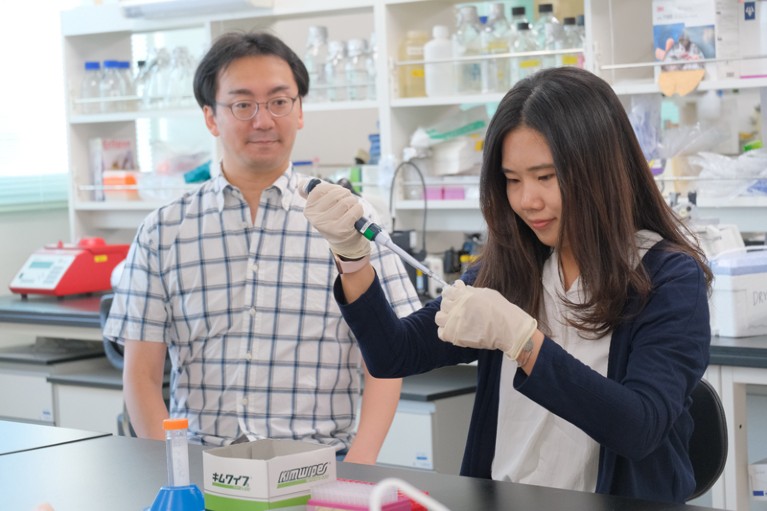

HITOSHI TAKIZAWA: Get institutional support to streamline the process

Stem-cell biologist and director of the International Research Center for Medical Sciences at Kumamoto University in Japan.

Medical-research internships at Kumamoto University are run by an institute rather than a lab.Credit: IRCMS, Kumamoto University

I established our internship programme in 2015 to recruit international students to our institution. We provide opportunities for undergraduate, master’s and PhD students to spend one to two months doing research in one of our labs, and we cover their travel and accommodation expenses up to US$1,500. So far, we’ve had 60 interns from 26 countries, and 16 of them have chosen to come back for graduate degrees or postdoctoral positions.

When I started the programme at my research centre, I was vice-director and able to set aside a small portion of the centre’s budget for interns. It was challenging to advertise it at first because we didn’t have a webpage or any media to promote the internship programme, but since we developed those resources over a decade ago, it’s grown a lot. We get about 60 applicants each year for just 10 intern positions.

Having an internship programme run by an institution instead of an individual lab is helpful for multiple reasons. It streamlines the application process, provides funding and can hold lab leaders accountable for providing good experiences. We currently have 15 labs involved in the programme and I typically host one or two interns each year. At the moment, I’m preparing for an intern to come from the United States. In the past, I’ve hosted interns from Indonesia, Bangladesh, Kazakhstan, India and the United Kingdom.

Beyond the lab, I hope interns immerse themselves in Japanese culture and language during their time here. I always encourage them to explore the city and interact with local people if they can. The ultimate goal is for them to enjoy the scientific process and everything that comes with it.

VIOLET MAKUKU: Partner with industry to help prepare students

Quality-assurance specialist and director at the Global Quality Assurance Association in Accra, Ghana.

As a quality-assurance specialist, I conduct assessments to help universities and educational organizations improve. Over the past decade, I’ve evaluated library systems, teaching environments, catering services and internship programmes. In 2022, my colleague and I wrote a paper discussing how to improve internship programmes at African universities1.

Running a successful internship programme requires accountability, transparency and effective communication. Sometimes, interns don’t feel a sense of responsibility because their positions are temporary. This can lead them to not come to work or to rush through their tasks. One way lab leaders can address this is by developing assessment tools that outline expectations and goals so that both interns and their mentors are accountable.

Nature Masterclass: Interpreting scientific results

Providing compensation makes accessing internships more equitable. Interns need to cover their housing, food and transportation expenses. Some interns are highly productive and are a benefit to the lab or organization that they are part of, so I don’t see why they should not receive a stipend or salary for their work.

A good internship prepares students for their next steps after graduation. One way to do this is by partnering with local industries that are relevant to the interns’ career interests. For instance, the Durban University of Technology in South Africa developed a partnership with the sugar-cane production company Tongaat Hulett, which has laboratories near Durban. The company welcomed interns into their labs, covered their accommodation costs and assigned them to research projects related to the production challenges that Tongaat Hulett faced.

I have heard of some companies offering jobs to interns before or after graduation, showing how much of an impact a good internship programme can have.

ERIN SPEAR: Be generous with praise to motivate people

Disease ecologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and is based in Gamboa, Panama.

Because my work focuses on the role that disease and death has in the maintenance and resiliency of tropical rainforests, I need a large team to achieve intensive field, greenhouse and lab work. All of the interns that come to my lab join existing research projects. This approach is the best way for them to earn authorship on a publication.

Friends or foes? An academic job search risked damaging our friendship

Usually interns work with me for six months, which feels like the right amount of time for them to learn how to measure tree health and decay using various techniques and software programs, build a strong network of peers and professional contacts, and gain the confidence and clarity needed to progress to the next stage in their career, often graduate school. All interns receive a monthly stipend of $1,250, and some also receive a travel allowance to offset some expenses.

It can be challenging to keep everyone safe, especially if they’re working in an unfamiliar country while conducting fieldwork in a tropical rainforest. For instance, I once dealt with a medical emergency that resulted in a hospital trip in the middle of the night. Because we were working on an island, we had to take a 25-minute boat ride followed by a 40-minute ride in an ambulance to get to the hospital. When you’re hosting interns far from their home country, you’re never off duty and you need to be their support system.

Good mentors consistently demonstrate that they value their interns by regularly telling them how much they value them, both in private and in public. Saying ‘thank you’ and ‘I appreciate what you’re doing’ is one of the easiest things that you can do and it goes so far. Praise is 100% the best motivator. I haven’t encountered a single exception to that in my lab.

It’s also important to be transparent, honest and willing to have hard conversations about how interns can improve their experience and behaviour in the lab. For example, I’ve had some interns who do not participate in literature-review meetings because they don’t fully understand the papers. I arrange one-to-one meetings with each intern to explain how their participation might be improved. I lead those conservations by saying that I care about them and want to see them succeed. It’s important that they understand it’s good to have difficult conservations with people who care about you and who are willing to provide feedback so problems don’t persist.

I try to choose interns who create a diverse team in terms of skill set, gender, educational background, country of origin and language spoken. Peer-to-peer learning and bonding is so important, and having a close cohort helps interns to build their professional and social networks as they move forward in their careers. I’m always amazed by how much interns grow during their time in my lab. The hardest part is watching them leave.