In December, the UK national fertility regulator — the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) — recommended that the government extend the length of time for which human embryos can be grown in culture from 14 days to 28.

Even though the UK government has not announced any plan to revise its laws in light of this recommendation, the HFEA’s announcement could have global ramifications (see go.nature.com/42j3pzp). As the first statutory body to regulate in vitro fertilization (IVF) and human-embryo research, the UK regulator has long shaped how other countries approach governance in this field.

Since the ‘14-day rule’ was established in 1990, it set a limit that has been widely accepted by scientists, ethicists and policymakers in many countries. It has helped to maintain public trust in embryo research while enabling scientists to investigate the first days of human development — work that is crucial to understanding the origin of some congenital diseases and to design and improve IVF techniques.

Guidelines on lab-grown embryo models are strong enough to meet ethical standards — and will build trust in science

A structure called the primitive streak — a visible indicator that the embryo’s body axes are forming — appears around 14 days after fertilization. Before the primitive streak forms, an embryo can still split to form twins, making it less clearly an individual. For this reason, 14 days or primitive-streak formation — whichever occurs first — was chosen as a pragmatic cut-off point.

However, scientific advances mean that it is almost certainly possible to culture embryos beyond 14 days1. By culturing them for up to 28 days, researchers could learn more about crucial subsequent developmental stages and the processes that occur before neurons and sensations arise, such as the start of organ development and the formation of the placenta. A visible indicator — closure of a structure along the embryos back called the neural tube, which goes on to form the central nervous system — marks a clear cut-off point at around 28 days, similar to the primitive streak at day 14.

Although some researchers and others have raised concerns that extending the deadline might lead to a slippery slope of further shifts that go beyond ethically defensible boundaries2, this need not happen.

Many scientists and other authorities are reconsidering the 14-day limit3–6. The HFEA’s announcement means that there’s a pressing need to consider how long-standing embryo-research frameworks might be revised in a responsible way.

As an international group of scientists working in human-embryo research, stem-cell biology and translational research, we have observed the scientific potential and ethical dilemmas of embryo research at first hand. We’re also involved in ongoing dialogue with regulatory bodies. On the basis of these experiences, we propose that the research limit be extended to 28 days or complete neural-tube closure, whichever occurs first — in a similar way to current 14-day policies. We call for a collective effort by scientists, policymakers, ethicists and the wider public to navigate this transition.

Why 28 days?

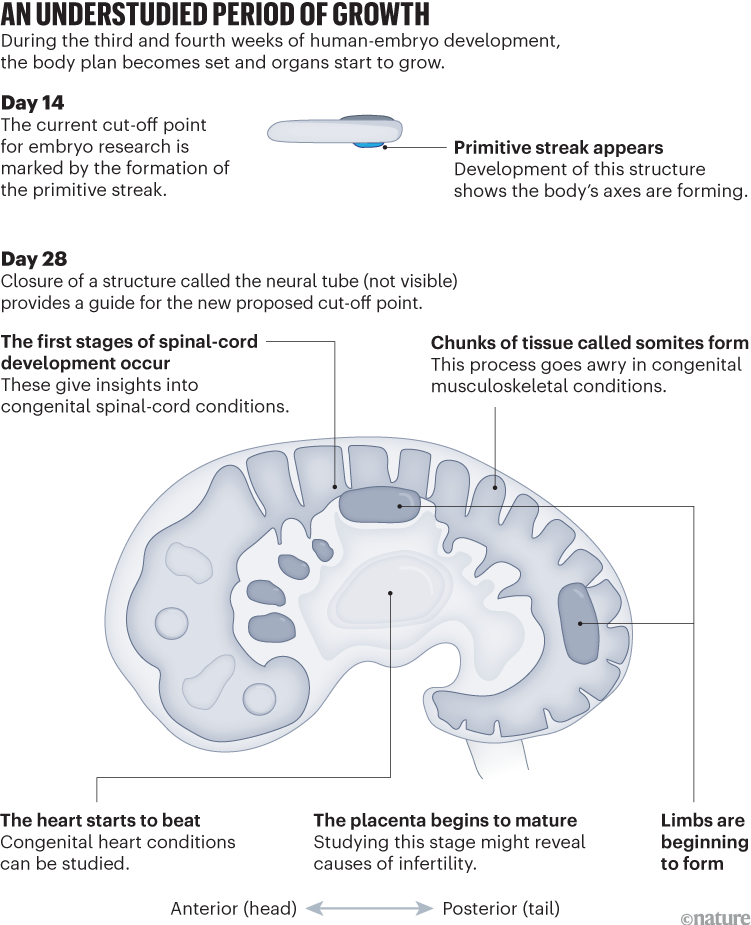

The third and fourth weeks of human development have remained understudied because researchers are not permitted to culture human embryos past day 14, and samples of embryos and materials that have been aborted earlier than day 28 are scarce. Yet, we know from studies in other animals and from rare samples that embryos go through crucial changes in this second two-week period (see ‘An understudied period of growth’).

Source: G. J. Tortora & B. Derrickson Principles Of Anatomy And Physiology 15th edn (Wiley, 2017).

Shortly after 14 days, the first tissue layers emerge, laying the groundwork for the embryo’s body plan. By the point of neural-tube closure, the growing human embryo has clear head and tail ends — but has not yet developed neurons, without which there can be no consciousness, pain or other sensory perception.

By day 28 the heart has started to beat. Buds that will become limbs have formed, but hands and feet will not develop for several more weeks. Other structures have also started to form: the beginnings of the gut; blocks of tissue that will go on to form the skeleton and muscle; and the beginnings of other internal organs.

Studying how and why these first steps of organ formation sometimes go awry could help researchers to understand conditions such as congenital scoliosis (a curved spine), anencephaly (in which parts of the brain and skull are missing) and congenital heart disorders.

Why researchers should use human embryo models with caution

The cells that will become sperm or eggs also arise around day 14 and migrate to the nascent gonads during the following weeks. Meanwhile, tissues that support the growing embryo — including the placenta — begin to mature. Analyses of how sperm, eggs and supportive tissues begin to develop could help researchers to pinpoint causes of infertility, pregnancy complications and inherited conditions, paving the way for earlier interventions and better reproductive outcomes.

What’s more, extending the 14-day rule could help to maximize the potential of stem-cell-derived embryo models3. These structures, which are designed to mimic all or some stages of embryonic development7, are subject to the 14-day rule in some countries8. The hope is that these models can be used for studies that require many samples — to test how drugs and other chemicals affect development, to conduct genetic screening, to analyse developmental anomalies and to improve engineering methods to grow cells and organs for regenerative medicine. But it’s crucial to know how closely these models mimic actual embryos — an extension of the 14-day rule would allow for better comparison.

In our view, a limit of 28 days or neural-tube closure would maintain clear boundaries on experimentation.

There are good reasons to draw the line at 28 days. The closure of the neural tube provides a clear stopping point that makes governance and oversight easier. The availability of aborted material that is donated to research is much higher after 28 days. And, after four weeks, the body plan is largely set. Many individual tissues and organs develop relatively independently after 28 days, and so can be studied using aborted tissue without needing whole embryos.

Ethical considerations

No global consensus exists on when personhood begins. Some people hold that life’s moral worth begins at conception. The 14-day rule never resolved this debate; it was a pragmatic, political compromise.

Others point to the emergence of human-like features. Milestones that can convey emotional weight, such as the development of a heartbeat, are likely to cause concern. An erosion of a previously sacrosanct boundary might raise slippery-slope concerns about research eventually leading to eugenic practices or ‘designer’ embryos. There might also be concerns about consciousness or sentience, the ability to feel pain or react to environmental stimuli, such as light, sound, temperature or touch. However, current evidence indicates that the neurons needed for these capacities do not develop until an embryo is at least eight to ten weeks old, and might not form functional neuronal circuits until much later9.

Any reforms must therefore be transparent, firmly regulated and based on clear ethical and moral boundaries10. This can help to reassure the public that researchers want to better understand human-embryo development, improve IVF treatments, reduce the number of miscarriages and prevent congenital conditions and diseases — and that they will not use embryos for more-controversial studies.

Collectively, we think that extending the embryo-culture limit to 28 days, or neural-tube closure, would offer the promise of unique scientific and clinical insights. However, any increase must not be merely legislative — it should involve nuanced ethical oversight and careful dialogue with understanding from both sides11.

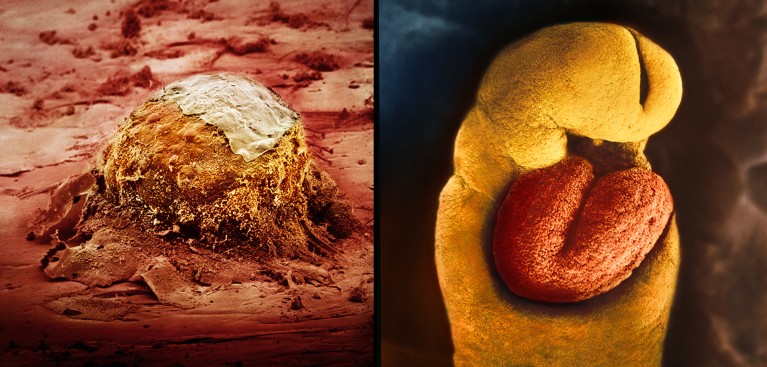

A human embryo embedded in the wall of the uterus at 11 days after fertilization (left). At 24 days, the heart has just started to beat (right).Credit: Lennart Nilsson, TT/Science Photo Library

Scientists have debated whether an extension of the limit should occur in gradual steps6 — allowing scientific and ethical review at several points between 14 and 28 days — or in a single jump. We recommend a single step. In our view, this approach is preferable because it would streamline governance and public engagement, and provide one clear boundary around which all oversight, communication and public dialogue could be structured.

We imagine the approach would first be rolled out in one or two regions — such as in the United Kingdom under the guidance of the HFEA — and then iteratively adopted by other countries. We urge policymakers and research institutions to take the following steps.

Public engagement and accountability. Careful consultation with the public, conducted and concluded well before experimental work begins, is essential to try and ease concerns and to help shape guidelines6.

Some previous examples highlight how to aid effective debate. For instance, the HFEA’s dialogue on a specialized form of IVF called mitochondrial replacement therapy showed the value of multiple types of engagement across several locations, with a diverse cross-section of the population (see go.nature.com/43tyg9i).

Similarly, public engagement related to extending the embryo-culture limit should involve dialogue events (formal discussions between multiple stakeholders)11, forums, citizen panels and surveys. Although these can be conducted by academics or relevant organizations, it is useful to incorporate specialist dialogue organizations that have expertise, but no direct interest in the outcomes. Examples and advice from the United Kingdom can be found through a public-engagement programme called Sciencewise. Researchers, policymakers, ethicists, community leaders and health-care professionals should all be involved in open dialogue with faith communities, patient-advocacy organizations and the broader public. Previous public engagement in Japan12 and in the United Kingdom — around the limits of embryo research and on the use of stem-cell-derived embryo models13 — shows that this approach can foster nuanced debates and minimize the risk of inflaming fears.

Scientists should not make assumptions about areas of public concern. Feedback from the public should be used to help shape regulations for any extended embryo cultures. It should prompt adjustments in protocols and help to inform how guidelines are implemented. If strong ethical or societal concerns arise, researchers and regulators must be prepared to modify projects accordingly.

Pilot projects. Before adopting new guidelines across a country, a few accredited centres could be licensed to extend the embryo-culture limit. The groups or centres would be chosen by national regulators — in coordination with professional societies and ethics committees — on the basis of established expertise in embryo research, robust ethical oversight committees and transparent track records of compliance.

Once a group succeeds in culturing an embryo to the point of neural-tube closure or day 28, a comprehensive scientific and ethical review would ensue. Licensing can eventually expand to all suitably regulated centres in a nation, if the review concludes that the data provide clear insights — allowing researchers to map migration of the precursors of sperm and egg cells, for example, or study the beginnings of placental development — and that public trust remains intact.

Yes to global standards for research — as long as they are truly global