Illustration: Sébastien Thibault

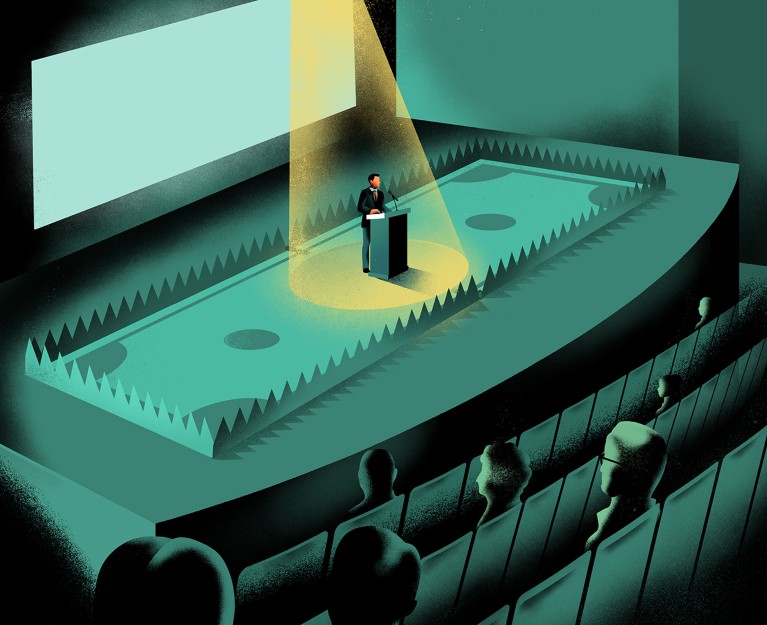

After coming across a UK conference that sounded interesting, Carme Arnan Ros, a laboratory manager and research technician at the -Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, Spain, was concerned. The event was organized by a private UK company whose name was similar to that of a prestigious university, although they were not related. She couldn’t be sure that this wasn’t a ‘predatory conference’ — one that typically is weak on organization and academic merit, focusing instead on profitability. Sometimes, these conferences come with misleading claims to entice researchers into attending.

So Arnan did her research: she verified with the venue that the conference was taking place there. She contacted some announced speakers and companies that would be present. She also sent e-mails and messages on the professional networking platform LinkedIn to speakers who had attended the conference before.

The results were mixed. She couldn’t find the programme for either the previous year’s conference or the upcoming one online, which worried her. A previous attendee didn’t recommend paying to present a poster “because the meeting is more intended for networking rather for scientific discussions”. Another attendee “told me that the meeting was good for applied and translational sciences rather than basic biology”, Arnan said. Even after speaking to several people about the conference, she still wasn’t sure.

Given that scientists have limited time, energy, money and perhaps carbon budgets for attending international conferences, how can they decide which ones are worth attending? Some experienced conference-goers offer a few suggestions.

Check the scope and focus

Like many researchers, Rose Joudi seeks to optimize her conference travel. And her employer, Carya, a non-profit organization in Calgary, Canada, that provides carer support, counselling and other programmes to strengthen families and communities, doesn’t usually fund conference travel.

Joudi had been seeking opportunities to learn about European gerontology and present her research on Carya’s project on abuse of older people in minority ethnic communities. So she planned to attend the conference of the British Society of Gerontology, in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, last July. But when a colleague on LinkedIn later told her about a gerontology conference in London that would take place only a week after the Newcastle one, it seemed like a fortuitous opportunity to give her talk twice.

Bats on film: scientific storytelling from a recovering academic

This event — the European Conference on Aging & Gerontology, run by the International Academic Forum (IAFOR), a non-profit organization based in Nagoya, Japan — was also attended by a Nature reporter investigating the different types of academic conference.

Joudi reached out to the conference organizer beforehand, and their communications were promising, she thought. It wasn’t until a few days before the event, when she was reading the presentation abstracts to decide which talks to attend, that she became confused. Among the variety of topics, one that kept cropping up was children’s education. “I thought, ‘Am I looking at the right conference timetable?’ So that caught me off guard.”

The IAFOR’s conference model often involves several general conferences that occur at the same location and have overlapping schedules. Non-academics can give presentations, and IAFOR members receive discounts on registration fees. Attendees also often find themselves conducting some of the conference administration themselves: they review each other’s abstracts, help to time each other’s talks and chair multi-speaker sessions.

The London conference had a combination of themes, including gerontology, education, language learning and the arts and humanities — and hosted several hundred people. In the first two days of the conference, many of the keynote speeches were delivered by academics working for the IAFOR or who were on the -education-centred conference committees. The poster sessions for this portion did, however, include gerontology topics. In one case, in lieu of a poster, a researcher had printed out their research manuscript on A4 paper and pinned it to a board. Because almost nothing on these first two days was relevant to her, Joudi didn’t stay for long. Eventually, she thought, “I love London, and there’s so many other things that I could be doing right now, exploring and just walking around and appreciating the weather. And I thought ‘That’s what I’m going to do.’” So she left.

A discerning eye is needed when choosing which conferences to attend.Credit: Robert Stainforth/Alamy

These first two days of combined keynote and poster sessions were followed by two days of in-person presentations spread across ten rooms (with audiences of about 7–25 attendees) and one day of online presentations. Only one of these days, and one of the conference rooms, was focused on gerontology. “I came from Canada thinking that this was purely gerontology,” Joudi says. “When you invite hundreds of people from a variety of disciplines that don’t necessarily overlap, I think it’s a bit daunting.”

Joudi wasn’t the only disgruntled gerontologist in attendance. A medical researcher from India who attended the same conference told a Nature reporter that, in his opinion, it was not good value for money. (On-site registration generally cost between £350 (US$453) and £450 for those who were not IAFOR members.) The event might be useful for early-career researchers who want to network, he thought — but for more established professionals, there wasn’t enough scientific content. And a physician from New Zealand who also spoke to Nature was angry. What irked her most was that she felt it had not been made clear during registration that this conference would focus on several fields simultaneously, although some of the communications about the conference seen by Nature’s reporters did indicate this overlap.

However, many attendees of this conference, and others put on by the IAFOR, were satisfied. The IAFOR sees its -interdisciplinarity as an asset, not a detriment. Education -researchers were especially well represented at this conference — but some of them who spoke to Nature’s journalists felt that the highly general, interdisciplinary model did not serve them well. The IAFOR did not respond to requests to comment from Nature’s -journalists.

More broadly, there are trade-offs between conferences that are more egalitarian and ones that are more selective. A key benefit of less elite conferences is the greater likelihood of being accepted for a presentation slot — although such a presentation could be delivered to fewer attendees with less expertise in the field. And if people without in-depth knowledge in a particular area are speaking about that topic, that’s a worrying sign, says David Kaye, a legal scholar at Pennsylvania State University in University Park, who runs the blog Flaky Academic Conferences. This blog was inspired by his forensic-science blog, whose readers were interested in discussing conference quality.

Kaye uses the term ‘flaky’ because he’s reluctant to endorse or decry journals or conferences. There are a number of conference practices he calls ‘borderline’, such as listing invited speakers as though they have committed. “Just because a conference is low quality does not mean that the practices are predatory,” he notes. For high-quality conferences, some selectivity in who speaks is needed, Kaye argues.

Check the organizer

Olivier Sandre, a researcher at the Organic Polymer Chemistry Laboratory in Bordeaux, France, is fortunate. He used to travel to two or three international conferences each year, deeming this necessary for his career. But now that he’s been promoted, he doesn’t feel this pressure and attends roughly one international conference every other year.

He’s been to some conferences that he describes as questionable. In 2017, he attended a conference on nanoscience that was poorly organized, he says, and had broad session themes (such as ‘energy materials’). But he and his fellow attendees managed to organize themselves, ultimately making the conference a fruitful one.

Predatory conferences are on the rise. Here are five ways to tackle them

Sandre advises students to be cautious with unfamiliar conferences, advising them to attend established ones at which they can be confident about making useful contacts. “When you’re younger, you need to make your name in your community,” he recognizes. “I think it’s part of the job of scientists to present their work results.”