The Doomsday Clock — a symbolic arbiter of how close humanity is to annihilating itself — now sits at 89 seconds to midnight, nearer than it has ever been to signalling our species’ point of no return.

Many threats, including climate change and biological weapons, prompted global-security specialists at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in Chicago, Illinois, to move the clock’s hands in January. But chief among those hazards is the growing — and often overlooked — risk of nuclear war.

“The message we keep hearing is that the nuclear risk is over, that that’s an old risk from the cold war,” says Daniel Holz, a physicist at the University of Chicago, who advised on the Doomsday Clock decision. “But when you talk to experts, you get the opposite message — that actually the nuclear risk is very high, and it’s increasing.”

From Russia’s grinding war in Ukraine and the simmering tensions between India and Pakistan that flared in May, to the US and Israeli attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities in June, the world is not short of conflicts involving one or more nuclear-armed nations.

AI and misinformation are supercharging the risk of nuclear war

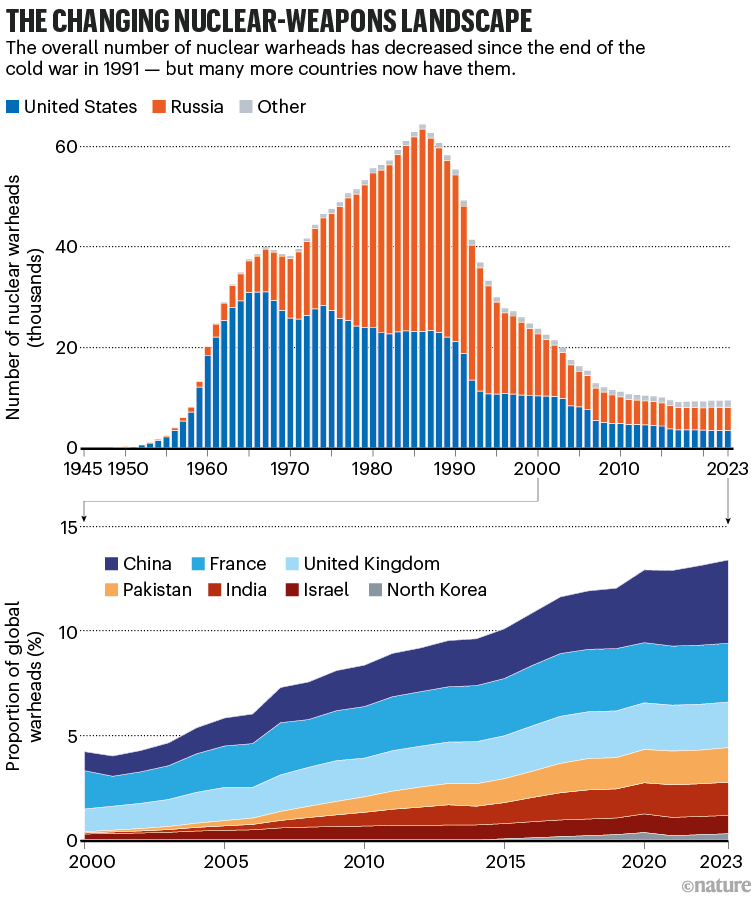

But it’s not just the number of clashes that have the potential to escalate that are causing consternation. The previous great build-up of nuclear weapons, the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union, essentially involved two, reasonably matched superpowers. Now, China is emerging as a third nuclear-armed superpower, North Korea is growing its nuclear arsenal and Iran has enriched uranium beyond what is needed for civilian use. India and Pakistan are also thought to be expanding their nuclear arsenals. Add to this the potential for online misinformation and disinformation to influence leaders or voters in nuclear-armed nations, and for artificial intelligence (AI) to bring uncertainty to military decision-making, and it’s clear that the rulebook has been ripped up.

“Eighty years into the nuclear age, we find ourselves at a reckoning point,” says Alexandra Bell, president and chief executive of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Amid this fraught landscape, scientists are working to prevent the world from annihilation. At a three-day conference in Chicago that started on 14 July — almost exactly 80 years after researchers and the US military tested the first atomic weapon — dozens of scientists, including Nobel laureates from a wide array of disciplines, met to discuss actions to prevent nuclear war. They released a fresh warning about its risks, as well as recommendations for what society can do to reduce them, including calling on all nations to speak transparently to each other about the scientific and military implications of AI.

Dawn of a nuclear age

The emerging multipolar world disrupts a tenet of nuclear security that helped to avoid nuclear war in the past. The principles of nuclear deterrence rest on the assumption that no nation wants to start a war that is bound to have devastating consequences for everyone. This meant having distributed nuclear arsenals that couldn’t be taken out with one strike, diminishing any incentive to strike first, in the knowledge the enemy would strike back and the consequence would be ‘mutually assured destruction’. It also meant clarity among nuclear-armed nations about who had what strike capability, and therefore what the possible consequences of any attack might be. A fragile stability prevailed, thanks to backchannel communications between hostile nations and diplomatic signals designed to avoid misunderstandings that could lead to the accidental pressing of the nuclear button.

How a small nuclear war would transform the entire planet

The multipolar model is more complicated, making it harder to manage the communications. The existence of more nuclear powers also raises the possibility of smaller nuclear wars that would still be utterly devastating, but wouldn’t necessarily lead to mutually assured destruction — weakening the deterrent to striking first.

What’s more, many of the backchannel communications that existed to help defuse nuclear tensions, such as informal discussions between US and Soviet scientists during the cold war, are no longer taking place to the same extent. Formal diplomatic channels are also fraying, stalled or interrupted by modern conflicts such as the Israel–Iran war, says Karen Hallberg, a physicist at the Balseiro Institute in San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina, who is secretary general of Pugwash, a group founded by scientists that works to eliminate nuclear arms and other weapons of mass destruction. “The most worrying fact is the current tendency of competition instead of cooperation, in science and in international relations,” she says.

Some are calling the multipolar world a third nuclear age. The first was the cold war, from the aftermath of the Second World War until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; and the second was during the 1990s and 2000s, when the United States and Russia scaled back their nuclear arsenals (see ‘The changing nuclear-weapons landscape’).

Source: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Nuclear Notebook

Misinformation’s cloud

The power of the Internet and social media to amplify misinformation — and its close cousin, disinformation, the deliberate spread of false facts — only add to the fragility of the new situation. Both can cloud delicate discussions around nuclear deterrence and raise the risks of military escalation.

Take the India–Pakistan conflict in May, which started when India launched strikes on Pakistan following a terrorist attack. Pakistan retaliated and the two countries launched missiles and other weapons at each other, with casualties on both sides. News and social-media channels were flooded with false claims of military triumph, including AI-generated images purporting to show enemy targets that had been destroyed. Global-security specialists worried that the disinformation about the scale of destruction could trigger escalation into nuclear war.

That didn’t happen: after four days of conflict, India and Pakistan agreed to a ceasefire following pressure from the United States. But it’s not hard to imagine how disinformation could nudge a leader of a nuclear-armed nation into deciding to use nuclear weapons, says Matt Korda, a nuclear analyst at the Federation of American Scientists in Washington DC, which works to minimize the risks of global threats. For instance, a rogue actor wishing to stir up trouble could start a false rumour on social media aimed at convincing US news consumers that Iran has built a nuclear weapon. Such fears might then trickle through to outlets that are closely watched by the US president and end up influencing his actions. “To influence that leader, you have to influence the domestic base of the United States, which I think we’ve learned is incredibly easy to do,” Korda says.

Fog of AI war

Another emerging issue is the role that AI might have in decisions about whether and how to unleash a nuclear weapon. The US Department of Defense is using AI tools for planning and battlefield operations in conventional warfare. Its top official in charge of nuclear forces, Air Force general Anthony Cotton, said last year that AI can help to speed up nuclear command-and-control decisions.

AI companies have begun partnerships with the US military. In June, Anthropic, in San Francisco, California, announced a set of classified Claude Gov models, based on its publicly available Claude AI assistant, that will be used for US national-security needs. In January, OpenAI, also in San Francisco, announced a partnership with US national laboratories that includes assimilating the firm’s models into the nuclear-weapons domain. China and Russia are also reportedly integrating AI tools into both conventional and nuclear warfare.