The University of Virginia in Charlottesville on 17 October rejected an offer from the administration of US President Donald Trump to sign a higher education ‘compact’.Credit: Peter Morgan/AP Photo/Alamy

US President Donald Trump asked US universities earlier this month to sign a ‘compact’ aligning their student admissions, hiring and research with his administration’s priorities — or risk forfeiting federal research funds. And many scientists have been calling on their institutions to reject the offer.

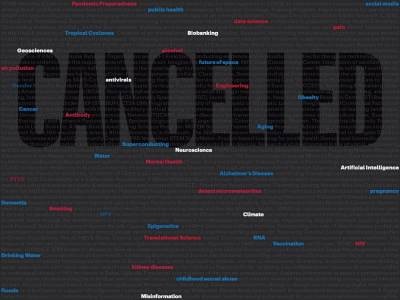

How Trump’s attack on universities is putting research in peril

“Short-term gain in research funding is not worth giving up the power that we have as scientists,” says Caitlin Hicks Pries, a biologist at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, who signed a petition against her school signing on to the compact. “We want our research funded, but we want it funded based on the quality of our ideas and the quality of science.”

Six of the nine universities initially invited to take the 1 October offer have now rejected it: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge; Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island; the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) in Philadelphia; the University of Southern California in Los Angeles; the University of Virginia in Charlottesville; and Dartmouth.

Some, including MIT, have echoed their researchers’ concerns, citing the importance of academic freedom in their rationale. “In our view, America’s leadership in science and innovation depends on independent thinking and open competition for excellence,” MIT president Sally Kornbluth wrote in a public statement. “Therefore, with respect, we cannot support the proposed approach.”

In a 12 October post on his social-media platform Truth Social, Trump informally expanded the compact offer to all US universities. And schools in Kansas, Arizona and Missouri were invited by the White House last week to discuss it.

The US Department of Education did not respond to a request for comment on researchers’ concerns in this story. Nature instead received an automatic reply stating that there would be no response while the US government is shut down.

Higher education under attack

The Trump administration, complaining that US higher education has become too liberal, has been taking action against universities for months. One of the first of these was the attempt to cut billions in research funding at all schools by capping indirect costs at 15%. (These are costs for things such as electricity for laboratories, paid on top of research grants.) Federal judges have since blocked those plans, but the uncertainty it has caused for schools has, in part, caused some of them to reduce hiring and admissions.

Harvard vs Trump: millions in grant money begin trickling back to scientists

Some institutions, including Columbia University in New York City and Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, had their federal research funding frozen. Columbia agreed to pay US$220 million over three years and to a number of other concessions to restore its grants. Harvard, however, sued, and a judge ruled in its favour, giving its research funding back.

For Timmons Roberts, an environmental studies researcher at Brown, the prospect of a compact felt all too familiar. In July, his university agreed to pay the US government $50 million to restore its research funding, which had been frozen since April. Before Brown rejected the compact, Roberts spoke at a rally where he and his colleagues urged the institution to turn it down. Agreeing to the ‘deal’ won’t stop the Trump administration from asking for more in the future, Roberts says.

The compact was heavily shaped by billionaire financier Marc Rowan. In a New York Times op-ed explaining his involvement, Rowan stated that the compact was “intended to promote excellence in core academic pursuits and to protect free speech” while reforming a “broken” system.

Will US science survive Trump 2.0?

University presidents said they agreed with many priorities of the compact, such as academic excellence and reintroducing standardized tests for admissions, which some institutions have already done. But the compact would additionally alter university admissions, by preventing officials from considering factors such as sex, race or nationality when deciding which students to admit, and marginalise transgender and nonbinary people by defining people as only ‘male’ or ‘female’. It also imposes a 15% limit on the proportion of international undergraduate students at schools; none of the institutions initially invited to sign the compact are above that threshold.

Agreeing to the compact would additionally require schools with endowments over $2 million per undergraduate student to provide free tuition for those earning degrees in “hard science programs”. Tuition being too expensive is a real issue, “but I don’t think the way to fix it is to tell universities that they can’t charge it”, says Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at MIT who has been involved in faculty discussions about academic freedom and responding to the compact. “The federal government has every right to put conditions on recipients of federal grants, but the proper way to do that is through Congress,” which controls US funding. MIT meets the $2 million funding criterion; students whose families make less than $200,000 per year already receive free tuition.