Welcome to the healthier, happier world of 2030. Heart attacks and strokes are down 20%. A drop in food consumption has left more money in people’s wallets. Lighter passengers are saving airlines 100 million litres of fuel each year. And billions of people are enjoying a better quality of life, with improvements to their mental and physical health.

These are just some of the ways in which analysts forecast that the new wave of incredibly effective weight-loss drugs, known as GLP-1 agonists, might transform societies and save countries trillions of dollars in the long run. The best known is semaglutide, marketed as Ozempic for diabetes, and as Wegovy for weight loss. “Short of some crazy unfortunate side effect, this is going to change the world,” says Chin Hur, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University in New York City.

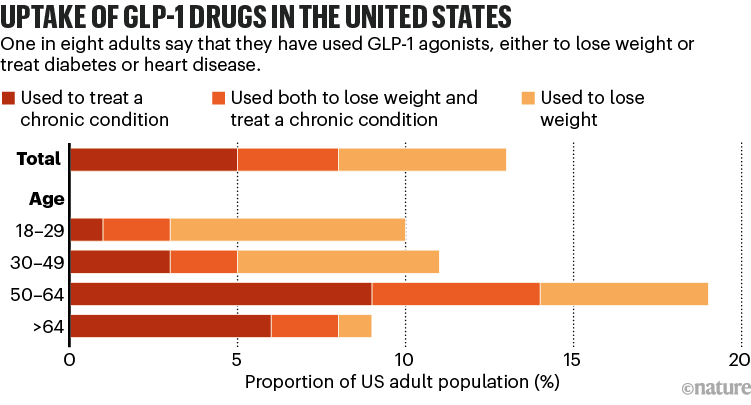

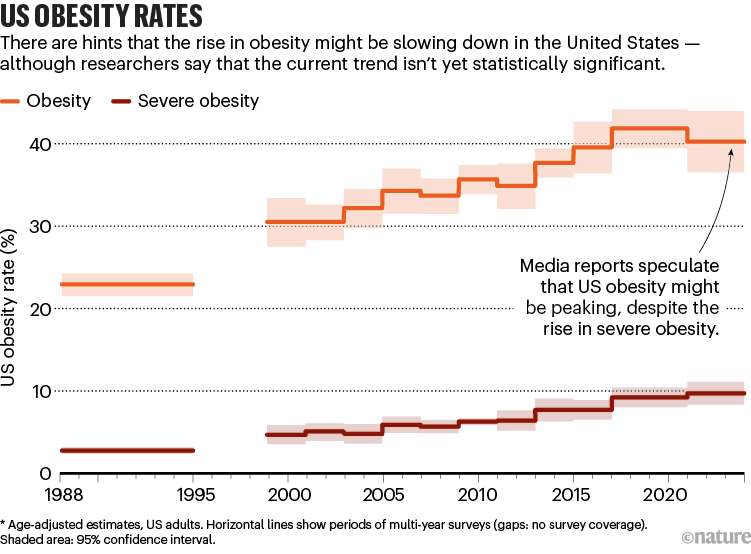

It might have already started. In the United States, where 12% of adults say that they have at some stage taken GLP-1 agonists for diabetes or weight loss (see ‘Uptake of GLP-1 drugs in the United States’), media reports suggest that obesity rates are falling, although scientists caution that the data are not statistically significant (see ‘US obesity rates’). Slowing or reversing obesity trends more widely — more than half of the world’s population is expected to be overweight or have obesity by 2035 — would have myriad ripple effects. “The spillover impacts of obesity are enormous,” says Alison Sexton Ward, an economist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Source: KFF & US NCHS/CDC

But although scientists agree that the drugs could have huge impacts, there is a lot of uncertainty. Efforts to model the weight-loss drugs’ future impact are highly speculative for various reasons, ranging from their high costs to their long-term biological effects, and the big unknown of how people’s behaviour will change. All that has medical researchers and companies scrambling to gather more data and develop better tools to assess how weight-loss drugs might transform societies.

Source: KFF & US NCHS/CDC

Modelling a miracle intervention

Modelling obesity — and its prevention — has long been a staple of public-health research. One way of doing so is to create algorithms that simulate interventions, such as a tax on sugary drinks, or mandatory exercise programmes in schools. By shifting variables such as people’s willingness to cooperate or societal demographics, such models can estimate the health problems that would be prevented or the money that would be saved.

Such policy-based behavioural interventions usually have little effect on preventing weight gain or causing weight loss in the real world, at least in the short term. But the GLP-1 drugs could be different, says Theo Vos, an epidemiologist at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington in Seattle. Trials show that drugs such as semaglutide allow people to lose around 15% of their body weight in 16 months. Next-generation drugs could be even more effective. “This really works, and it works in quite a dramatic way,” says Vos.

The easiest things to model are the immediate impacts of a drug for an individual, including improvements both for physical ailments, such as reduced sleep apnoea, heartburn or joint pain, and in mental health, such as experiencing less social stigma. “If you lose weight, your quality of life improves immediately,” Hur says. Clinical trials suggest that the drugs seem to treat a host of other conditions, too, including addiction, Parkinson’s disease and infertility, but Hur says that it’s still too early to incorporate these benefits into models.

Why do obesity drugs seem to treat so many other ailments?

GLP-1 agonists do have downsides: many users experience nausea, gastrointestinal problems or muscle atrophy, and when people stop taking the drugs, they tend to quickly put the weight back on. Still, GLP-1s are probably different from previous ‘miracle’ weight-loss drugs such as fen–phen (fenfluramine/phentermine), which was banned because of its severe side effects, says Nicolas Rasmussen, a science historian at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. GLP-1s have been used to treat diabetes for many years and seem to be safe for most people.

Nevertheless, Rasmussen says, “history does tell us they’ll be overused”. Although the drugs might be clearly beneficial for people whose obesity is harming their health, people who take them simply to lose a few kilograms must set that benefit against the side effects. That hasn’t seemed to slow demand, especially as social-media influencers and celebrities promote the drugs for weight loss. Pharmaceutical companies that produce some of the key drugs have experienced shortages.

Economic forecasts

Beyond the effects on individuals, researchers expect that wide use of GLP-1 drugs could have some startling broader economic impacts. Analysts project that a global market already worth US$47 billion this year will grow ten-fold by 2032. People in certain industries, such as the food sector, are already becoming worried by the popularity of the drugs. An analysis by US investment firm Morgan Stanley predicted that US calorie consumption could drop by 1.3% by 2035. Last October, John Furner, the chief executive of retail company Walmart U.S., said that the company had seen a drop in food sales that it attributed to weight-loss drugs. Some analysts have projected less-obvious effects. US investment firm Jefferies predicted for one US airline that, if every passenger flying with it lost roughly 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms), the airline would save more than 100 million litres of fuel per year. Other reports found potential impacts for companies producing medical devices such as knee implants for arthritis or masks for sleep apnoea, more demand for smaller cars, and reconfiguration of land and building use if people walk more in commercial areas.

On a global scale, the ripple effects on economies could be even greater. For instance, studies suggest that young people with obesity perform worse in school1 and that girls are less likely to go on to pursue higher education than their non-obese counterparts are2, even when controlling for factors such as race, income and parents’ socioeconomic level or education. Obesity-related health problems have also been shown to lead workers to take more sick days — which in turn can lead to workplace discrimination.

Costs such as these account for more than 2% of global gross domestic product (GDP), according to a 2022 report on obesity rates in 161 countries3. If the rate of obesity increase was suddenly slowed by 5% relative to current trends, the report found, countries would save more than $429 billion each year between 2020 and 2060. Such analyses do not try to model the costs of drugs or any other intervention that could lead to lower obesity rates.

Unclear consequences

But when it comes to GLP-1 agonists, some of these predictions might be premature, says Ross Hammond, a systems scientist at the Brookings Institution, a think tank in Washington DC, because weight loss with GLP-1 agonists might not directly translate into global cost savings and health improvements. “I’d be very uncomfortable saying the cost estimates [in those studies] are costs that could be saved by everyone being on Ozempic,” he says. “It’s not clear all those consequences would be good.”

For instance, an economic principle known as moral hazard predicts that people tend to behave in risky or unhealthy ways if they face no consequence. It’s not yet clear whether people taking GLP-1 agonists adopt healthier lifestyles if they no longer have to worry about gaining weight, although some evidence suggests that the drugs reduce cravings for high-fat and high-sugar food. The same goes for exercise: research hasn’t yet shown whether people become more or less physically active if they lose weight with GLP-1 agonists.

Cheaper versions of blockbuster obesity drugs are being created in India and China

Hammond points out that exercise and healthy diets have benefits beyond weight maintenance. Reducing caloric intake alone won’t solve issues such as weak bones or muscles, driven by sedentary lifestyles and micronutrient deficiencies. “I’m a little worried that looking for a pharmaceutical solution will not address some of the bigger systems problems that we really face,” he says.

Vos agrees that modelling the health effects of weight loss with GLP-1 agonists isn’t straightforward. It’s unclear, he says, whether a drug that causes people to suddenly lose weight can be compared with an intervention that prevents them from gaining it in the first place. The duration of obesity might affect factors such as arthritis and cardiovascular risk, much as a person’s risk of lung cancer increases with the number of years that they smoked.

Michele Cecchini, a physician and economist at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris, says that there are other unknowns as well. For instance, many people regain weight years after undergoing bariatric surgery. That might turn out to also be the case for people who take weight-loss drugs for decades. “These are things that have a potentially huge impact at the population level,” he says.

Cecchini says that the OECD plans to release a report on GLP-1s’ economic impacts next year. His group has previously looked at the effects of obesity on factors such as education, workforce participation and health-care spending. Even climate change is affected when obesity rates rise. Carbon dioxide levels from food manufacturing rise to meet increased demand — particularly with red-meat production — and vehicles have greater emissions owing to heavier loads4.

The challenge with weight-loss drugs, Cecchini says, is the lack of long-term data. There’s a particular lack of independent studies, because many are funded by the drugs’ manufacturers, he adds.

Disparate outcomes

Some data are more solid than others. Researchers could probably confidently project the drug’s impact in people in their sixties and seventies with high body mass indexes (BMIs), says Zachary Ward, a decision-science researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts. The effects of obesity on conditions such as diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and certain cancers that affect this age group are well known.

A study of more than 17,000 people that was published last November5 estimated that Wegovy reduced the risk of heart attacks and strokes by 20% in people who had cardiovascular disease and were also overweight. And another research team estimated that 93 million people in the United States could benefit from Wegovy. If these people all took Wegovy, the team calculated, it would prevent 1.5 million cardiac events over ten years6.

But young people taking GLP-1 agonists are unlikely to encounter these diseases for many years, and factors such as lifestyles and environmental exposures can change over decades. “The longer you go, the more assumptions you make,” Ward says.

Some models show that younger people might benefit most from GLP-1 agonists — if they take them for the rest of their lives. Sexton Ward’s group found that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the drugs are less cost-effective for people with very high BMIs7. Rather, they can prevent more diseases in young people with BMIs between 30 and 40 — the lower end of the range for obesity. “That’s the range where it’s effective enough that 20% weight reduction will reduce the risk of comorbidities,” she says.

Obesity drugs aren’t always forever. What happens when you quit?

Their analysis found that, if everyone in the United States had free access to semaglutide, the resulting drop in obesity-associated diseases would save taxpayers $24.5 billion per year, although this would not include the cost of the drugs themselves.

Sexton Ward agrees that predicting population-level health and economic impacts is difficult owing to scarce data. But she highlights one idea: in a report funded by semaglutide-maker Novo Nordisk that she co-authored, her team found that the GLP-1s could produce much greater economic benefits for Black and Hispanic people in the United States than for white populations8.

US Black and Hispanic populations are, on average, more prone to obesity and related conditions than white populations are — largely because of societal inequalities such as lower average incomes and concomitant difficulties in accessing healthy food. Obesity, in turn, exacerbates other health disparities caused by environmental exposures and discrimination in health care.

“Over time, access to these drugs could begin to shrink some of these disparities,” Sexton Ward says. Although obesity isn’t the only cause of health inequality, she says, “I think it could be a step in the right direction.”

The price issue

Right now, however, the drugs are so expensive that only relatively wealthy people can afford them (although in some US states, there is government health-care coverage under a programme for low-income individuals). If influencers and celebrities can easily lose weight, Rasmussen says, the stigma against obesity might increase. That could further harm people on low incomes, who are most likely to face the social, economic and health consequences of obesity. “That gap will increase as long as it remains expensive,” he says.

The high cost is a particular problem for low- and middle-income countries, where obesity rates are growing twice as fast as in high-income nations, says Adeyemi Okunogbe, a health-policy researcher at the non-profit RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California. Of the estimated 5 million deaths each year caused by obesity-associated conditions, 77% occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Okunogbe says that obesity-related health-care costs put a double burden of disease on these countries, many of which are already fighting higher rates of infectious diseases. Other costs, such as lost wages owing to higher rates of illness and disabilities, are also magnified in lower-income nations. And in countries without national health systems, individuals would need to pay for GLP-1 agonists out of their own pocket. “It’s a long way off to consider this medicine in this context,” Okunogbe says.

Even countries with public health-care systems are struggling to work out how to pay for the drugs. The UK National Health Service currently funds semaglutide for individual weight loss for only two years, even though the drug must be taken for life to sustain its effect. And US law doesn’t require taxpayer-funded insurance programmes to cover weight-loss treatments (although the same drugs can be covered to treat diabetes). The drugs aren’t even close to affordable: an analysis last year9 by Hur’s group found that the cost of semaglutide would need to drop by 85% to make it cost-effective for adolescents. “The way things stand, there’s not going to be much impact on global health outcomes,” Ward says.

Cecchini says that the OECD’s analysis will consider the impact of cheaper generic and compounded GLP-1 agonist drugs, which are beginning to appear on the market in many countries. And some lawmakers, including in the United States, are beginning to push back on the high costs, particularly after an analysis found that Novo Nordisk could sell Ozempic for $5 per month and still make a profit10.

Until more people can afford the drugs, economists and public-health researchers hoping to look at global impacts are stuck with virtual models instead of studies of actual behaviour. “These drugs hold so much promise, but [the world] has to have access to realize it,” Sexton Ward says.