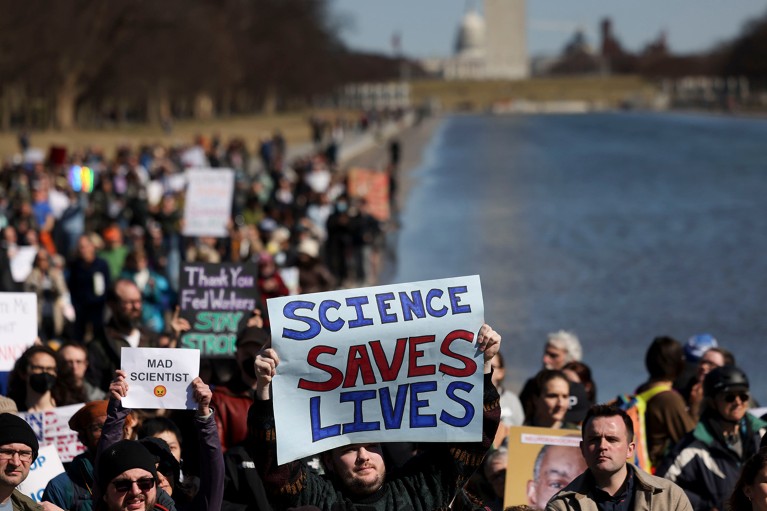

Demonstrators protested over cuts to science jobs and funding in Washington DC in March.Credit: Tierney L. Cross/Bloomberg/Getty

For the past six years, Lisa Neyman has been analysing marine vessel traffic to help find ways to avoid collisions with North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis). In January 2024, the marine mammal scientist left Florida’s state fish and wildlife agency to work as a contractor for the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which is based in Washington DC. “It was my dream job,” she says. “I was doing the science that informs regulation.”

That dream job was on the chopping block in February when the administration of US President Donald Trump decided to slash jobs — more than 58,000 so far — at dozens of federal agencies in the name of government efficiency. NOAA didn’t renew her contract.

Exclusive: a Nature analysis signals the beginnings of a US science brain drain

On Neyman’s last day of work, 28 March, she did what a growing number of federally funded scientists have done — added the Open to Work logo around her profile picture on LinkedIn. So far, she has applied to a handful of positions in water quality, climate solutions and combating illegal fisheries that she feels are purposeful and require her skill set.

But she doesn’t hold out much hope for a job using her extensive expertise working with humpback, beluga and right whales. “Without federal funding, marine mammal conservation jobs are pretty few and far between,” she says.

And the positions that do exist are highly sought after.

Along with the tens of thousands of researchers who have been let go from federal posts, thousands of federal grants have been terminated, prompting lawsuits that challenge the constitutional legality of the terminations. Nature’s careers team spoke to a dozen scientists who have been laid off from NOAA, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the US Geological Survey (USGS) and from universities as a result of federal funding cuts in the past two months. For example, on 6 May, Columbia University in New York City laid off roughly 180 employees because of grant terminations. Several of those interviewed requested anonymity to speak freely as they seek work, describing a bleak job market.

Beyond the federal government, there are two main employment sectors for scientists: academia and industry. To a lesser extent, there are also positions in non-governmental organizations. Amid the widespread federal funding freezes, universities and non-profit organizations have also scaled back recruitment. Economic uncertainty is adding to a dismal outlook for industry jobs. Sharp job cuts in the technology industry in 2024 have extended into 2025. The biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries report a 3-year low in the number of hiring positions, having shed some 24,000 jobs in 2024 (see go.nature.com/4dhmtmx). As a result, competition for existing US industry jobs is fierce.

US scientists who find themselves abruptly unemployed are turning desperation and defiance into fresh coping strategies and advice. But one thing is clear: whether they move abroad, pivot to other research areas or leave science altogether, their deep expertise is likely to be lost.

Brain drain

Many scientists are looking abroad. One postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, San Diego, is two and a half years into a project to develop a vaccine to prevent infectious disease. In February, her supervisor informed her that, because of cuts to vaccine research, he couldn’t guarantee her funding beyond December. Without more time for her research, her efforts could be wasted. Her mentors have offered moral support and advised her to look at jobs in Canada, Europe or Singapore. “Maybe the United States is no longer a priority for early-stage researchers,” she says, stunned by what she describes as a drastic shift in how the country values science.

Research institutions in Europe and Canada are actively recruiting US scientists. This month, the European Commission announced a €500-million (US$564-million) package for 2025–27 “to make Europe a magnet for researchers”. The funds come after Maria Leptin, president of the European Research Council in Brussels, described in February how Europe could be a “haven” for US scientists. The UK government and a German foundation are also developing funding schemes to attract US researchers.

Arrianna Lister plans to pursue an MD–PhD.Credit: Arrianna Lister

In April, Aix-Marseille University in France announced its €15-million Safe Place for Science initiative. Its aim is to hire 15–20 US researchers working on areas being targeted for cuts by the Trump administration, such as climate change or vaccines. “We really believe that science is international,” says university president Eric Berton. “It is important to show these people they are not alone. We want to offer scientific asylum to our colleagues,” he adds. The university received nearly 300 applications for the spots.

The full extent of any US brain drain won’t be known for years, but early signs suggest that the loss of expertise will come in many forms. Interviewees had honed expertise in climate change, ocean carbon cycles, detection of Alzheimer’s disease and men’s reproductive health, among other areas. Now, they are retooling their CVs and cover letters to showcase how their skills can be applied in other areas.

75% of US scientists who answered Nature’s poll consider leaving

“A lot of talent is being cast away. We’re talking about probably 18 months for all of that talent to be reabsorbed into the labour market,” says Jeff Strohl, director of research at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce in Washington DC. Until then, many scientists will have to make an unenviable choice: whether to put energy into sustaining their current expertise as related federal jobs are being cut, or to switch fields or sectors.

One researcher who has worked in various federal agencies for ten years, most recently as a hydrologist focused on the western United States, was laid off from the USGS in February. So far, she has sent out about 40 job applications. “I decided I have to get ahead of the game,” she says. “All of the jobs indicate that the hiring body is receiving more applicants than normal,” she adds. “It’s been so stressful. My career and life trajectory changes hourly,” she says. “It’s weird to feel like I’m willing to do anything at this point to get out of this country,” she says. “It feels like our only option.”

A NOAA research leader says her work on climate change and biodiversity is effectively frozen. Although she still has a job, she doesn’t expect it to last for long, given the gutting of the agency’s budget. She has applied for about ten jobs overseas and has contacted colleagues abroad looking for opportunities. “I’m not applying for jobs in this country,” she says. “I have to get out and I am hoping I can do so on my terms.”

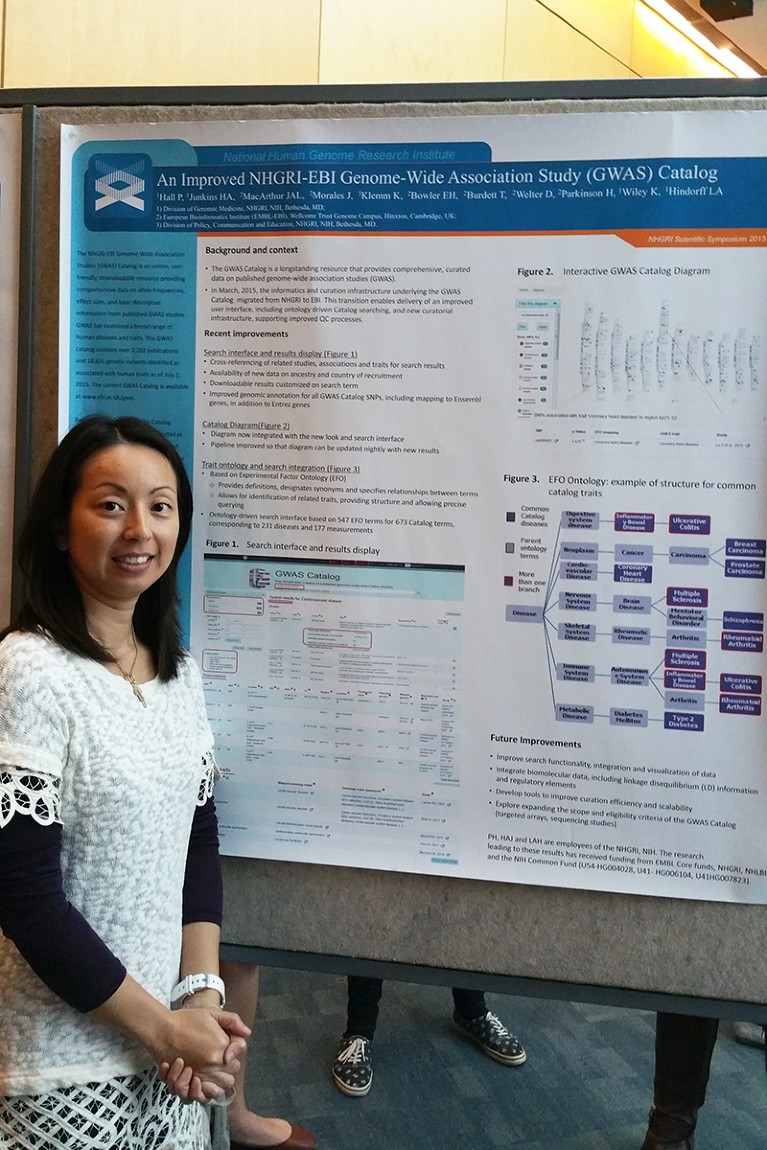

After being laid off from the US National Institutes of Health, data curator Peggy Hall is pursuing a master’s degree in bioinformatics.Credit: Peggy Hall

Researchers who can’t leave — owing to personal or other reasons — are identifying alternative careers. A researcher who has studied the ocean carbon cycle in academia and non-profit organizations for the past decade moved to NOAA just six months ago. “This was my last chance to get into federal service,” she says. Because she was still in her probationary year, she was part of the first round of lay-offs, then was reinstated on 17 March and fired again on 10 April. “We are rapidly overtopping what the existing job market can absorb,” she says of the race to find work.

If she hasn’t landed a job by July, her back-up plan is to earn a teacher certification. “I know my school district needs cool science teachers,” she says. Although she is comfortable reinventing her career, she bristles when describing how her expertise, and the federal money already spent to train her, will be wasted. “I represent decades of federal investment,” she says of the graduate and postdoctoral fellowships she has received from the US National Science Foundation, NASA and NOAA.

Finding other paths

Peggy Hall, a scientific data curator at the NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute in Rockville, Maryland, lost her job in a February lay-off. Hall had spent the past 15 years curating the institute’s genome-wide association studies (GWAS) catalogue of human DNA variants in diseases, analysing roughly 80% of published GWAS studies. After the lay-off, she felt mentally drained, anxious and overwhelmed. Colleagues on LinkedIn, which has emerged as a go-to place to find community, support and opportunities, gifted her thank-you notes and a ‘GWAS Data Hero’ badge to wear while she was mourning the loss of her role in the scientific enterprise. She was proud of her contribution creating a database to help scientists to efficiently find disease information and risk-associated genes. Not being able to continue makes her “feel crazy”, she says.

Hall, who has applied for 30 jobs, is getting certified in computer programming and machine learning and begins a master’s degree in bioinformatics this month. After processing her grief and anxiety, she says one good thing has come out of the ordeal: she’s realized her value. “Don’t underestimate yourself,” she advises (see ‘Exploring fresh terrain’ for other tips).

Many high-achieving scientists say that current events have emboldened them to do the work they always intended to do. For some, that means more education. Arrianna Lister was a research assistant at the University of California, Los Angeles, working on a project to improve HIV treatment in vulnerable populations and examine how historical racism has shaped how people seek care. When the NIH grant that funds Lister’s position was terminated, because of its focus on diversity, equity and inclusion, she turned her attention to applying for MD–PhD programmes to further her research goals. Would she consider going overseas to do that degree? “No,” she says. “Systemic racism in the United States is unique, and I would like to stay here to help bridge the gaps in minority health disparities that stem from these inequalities.”