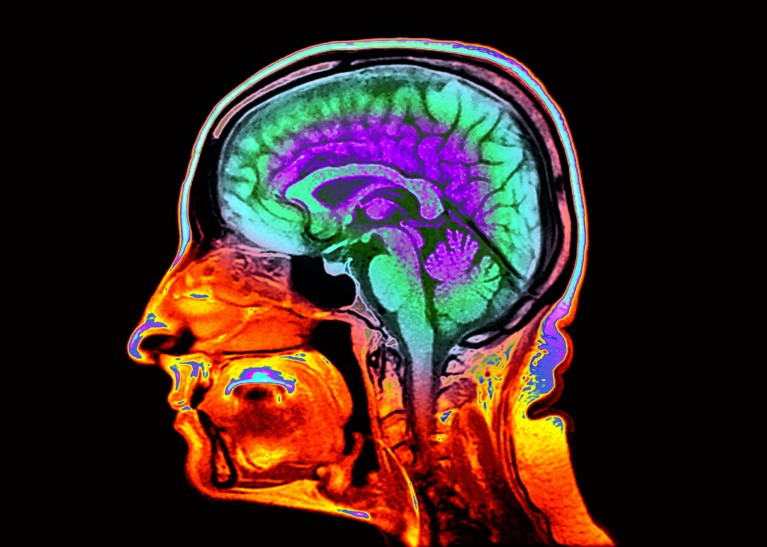

A magnetic resonance imaging scan (pictured, artificially coloured) of the brain can detail risk of memory loss and other cognitive difficulties.Credit: Zephyr/Science Photo Library

Telltale features visible in standard brain images can reveal how quickly a person is ageing, a study of more than 50,000 brain scans has shown1.

Pivotal features include the thickness of the cerebral cortex — a region that controls language and thinking — and the volume of grey matter that the cerebral cortex contains. These and other characteristics can predict the rate at which a person’s ability to think and remember will decline with age, as well as their risk of frailty, disease and death.

Although it’s too soon to use the new results to assess people in the clinic, the test provides advantages over previously reported ageing ‘clocks’ — typically based on blood tests — that purport to measure how fast a person is ageing, says Madhi Moqri, a computational biologist who studies ageing at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Imaging offers unique, direct insights into the brain’s structural ageing, providing information that blood-based or molecular biomarkers alone can’t capture,” says Moqri, who was not involved in the study.

The results were published on 1 July in Nature Aging.

Slowing the clock

Genetics, environment and disease all affect the rate at which a person’s body ages. As a result, chronological age does not always reflect the pace with which time takes its toll on the body. Researchers have been racing to develop new measures that can fill that gap.

Such ageing clocks could assess an individual’s risk of age-related illness early in life, when it might still be possible to intervene. They could also aid testing of treatments aimed at slowing ageing, by providing a marker that can track the effects of the intervention in real time.

Why eating less slows ageing: this molecule is key

A host of candidate clocks has appeared in the scientific literature — and in direct-to-consumer advertising — over the past decade. Many of these were developed by feeding reams of data, such as measurements of molecules found in the blood, into computer algorithms that determine which of the inputted parameters are linked with ageing. Often it is unclear why the measurements are correlated with ageing.

To develop an improved clock, Ethan Whitman, who studies brain ageing at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, and his colleagues began with a remarkable study of more than a thousand people who were born in Dunedin, New Zealand, between April 1972 and March 1973, and who have been periodically assessed by researchers since birth. In the most recent of those assessments, participants’ brains were scanned using magnetic resonance imaging.

Whitman’s team fed measurements made from 860 of those brain images into their algorithm and had it look for correlations between the brain-scan data and what the team called the “Pace of Aging”, a measure that incorporates data from all the Dunedin participants’ age-related declines in cardiovascular, metabolic, and immune function, as well as other physiological measures.