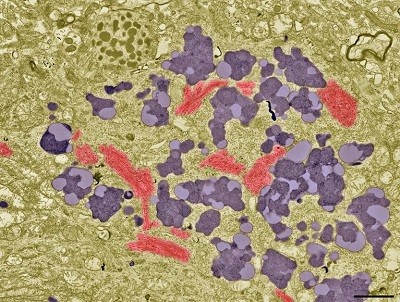

Researchers looked for markers of Alzheimer’s disease in more than 11,000 NorwegiansCredit: Tek Image/Science Photo Library

Nearly one in ten people over the age of 70 have Alzheimer’s disease dementia, shows a first-of-its-kind study that paired blood-based markers and clinical assessments to study the disease in Norway1.

That prevalence is in line with previous estimates for some other white populations2. But there were also unexpected differences, including higher disease rates than anticipated in individuals older than 85.

“This is very important work from a beautiful Norwegian study,” says Nicolas Villain, a neurologist at Sorbonne University in Paris who was not involved in the research. The study, published today in Nature, shows that blood-based tools can improve epidemiological estimates of neurodegenerative disease.

Blood tests are now approved for Alzheimer’s: how accurate are they?

But exactly how to use these tests remains controversial, warns Jason Karlawish, a geriatrician and co-director of the Penn Memory Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Blood-based markers can be helpful for physicians treating people with dementia and for answering research questions, but they aren’t ready to be rolled out widely as health screening tools.

“It is the kind of test that, in the wrong hands, could cause a lot of harm,” says Karlawish, who was not involved in the study.

From blood to brain

To assess the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), an international team of researchers turned to the Trøndelag Health (HUNT) study, a prospective health research study that started in 1984 and that has collected health data and biological samples from 250,000 Norwegians.

Using blood samples from 11,486 individuals in the study aged 58 and above, the team looked at levels of a protein called tau that has been phosphorylated at a specific site. Known as pTau217, this blood marker serves as a proxy for the build-up of amyloid plaque in the brain, a hallmark of AD. HUNT study participants over the age of 70 have undergone cognitive testing, enabling the researchers to compare pTau217 levels with the presence of dementia.

Around 10% of participants over the age of 70 had dementia and AD pathology, showing both cognitive impairment and high pTau217, they report. Another 10% had mild cognitive impairments and high pTau217. And 10% had high pTau217 but no signs of cognitive impairment, which the authors refer to as preclinical AD.

These findings are broadly in line with expectations, but there were surprises too.

Some 25% of people aged 85–89 had dementia and AD pathology, up from previous estimates of around 7% for men and 13% for women in this age group in Western Europeans3. And the incidence of preclinical AD in younger individuals was 8% in those aged 70–74, down from a previous estimate of around 22%.

Anders Gustavsson, a member of the team that compiled the earlier estimates, welcomes the latest data. “I’m not surprised that this study gets somewhat different numbers,” says Gustavsson, who is an adviser to the health economics consultancy Quantify Research in Stockholm.

Alzheimer’s decline slows with just a few thousand steps a day

The discrepancies probably reflect selection bias, says study co-author Anita Lenora Sunde, a physician and dementia researcher at Stavanger University Hospital in Norway. Previous estimates were made by recruiting participants for brain scans, and people with dementia might not have wanted to or been able to participate.

But other factors could also be at play, says Villain. The latest study uses a high pTau217 threshold to define its preclinical AD population, and so excludes people with intermediate levels of the protein and emerging pathology.

“If you lower the threshold, the prevalence suddenly increases,” says Villain.

The value of education

The study also found that people with lower education levels have higher pTau217 levels.