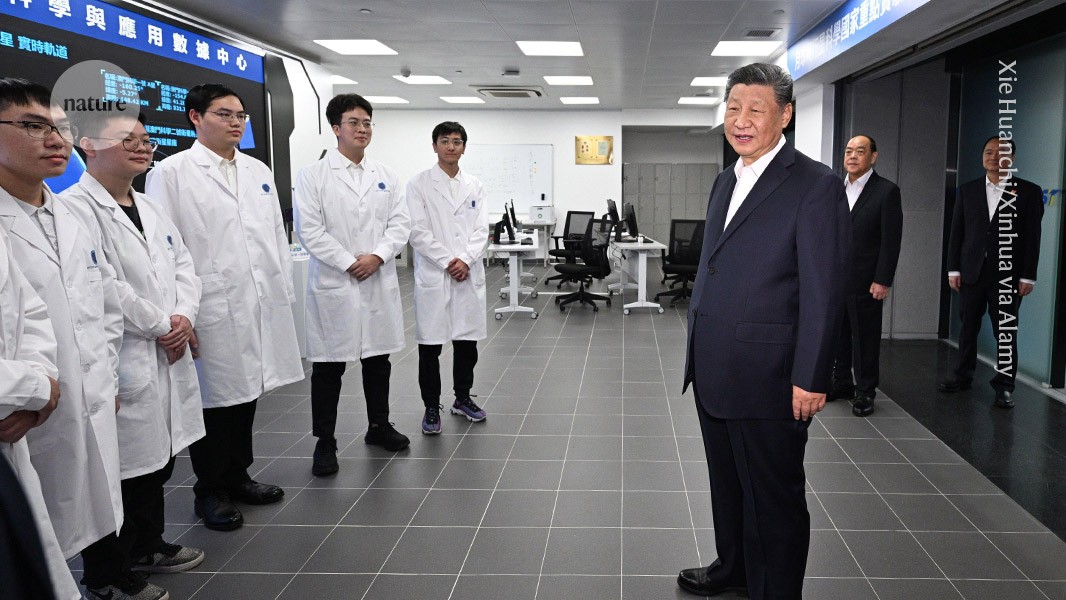

Chinese President Xi Jinping talks with researchers at the Macau University of Science and Technology.Credit: Xie Huanchi/Xinhua via Alamy

In central China, the largely rural county of Gulin in Sichuan province is offering PhD holders a lump sum 300,000 yuan (US $42,000) and a monthly allowance of 1,000 yuan to move there. The city of Taizhou in Zhejiang province will pay university graduates up to 100,000 yuan to resettle to the coastal locale. And Hunan province will provide a sum of up to 1 million yuan to doctoral students who move there from abroad.

Across China, cities and provinces are seeking researchers, students and innovators — both homegrown and from abroad. In return, they’re offering large sums of money, as well as housing, health care, work for their spouses and other benefits. That’s on top of the generous salaries being offered by universities, and research funding from the central government.

“The competition for talent is intense both across China and within different districts of the same city,” says Yanbo Wang, a science-policy researcher at the University of Hong Kong.

These efforts could soon benefit from the recent tightening of US immigration rules, particularly those targeting Chinese nationals, say researchers. On 28 May, Marco Rubio, the US secretary of state, announced that the country would start revoking visas of Chinese students and enhance scrutiny of all visa applications from China.

Some US researchers with ties to China might have been debating whether to return there. “The Trump administration has made that decision much, much easier than ever before,” says Wang.

Local and global

Recruiting researchers and highly skilled workers is central to China’s push for economic and social development and self-reliance. At an event last week to celebrate science and technology workers, China’s President Xi Jinping said: “A country’s technological innovation capacity depends on talent.”

In the past, China had a few central government policies designed to recruit talent from abroad. One was the Thousand Talents Plan, which aimed to attract elite international scientists to make the country a global leader in science and technology. But the United States and other governments began to worry that the programme could be a vessel for China to steal intellectual property or trade secrets. Although this was proved only in rare cases, Chinese talent programmes are still viewed with suspicion by US government agencies.

There are now hundreds of talent-recruitment policies at the central, provincial and city levels, says Wang. The initiatives are tiered, from highly competitive programmes seeking to attract elite researchers and innovators to those encouraging skilled workers to move to specific cities or regions.

Some programmes mainly target international researchers, including a continuation of the Thousand Talents Plan and the Overseas Young Elite Recruitment Program, which have essentially been reorganised under the High-End Foreign Talents Plan.

But most initiatives are open to talent based anywhere, including in China, reflecting the changing dynamics in the country, says Wang.

Two decades ago, overseas talent would have been considered the cream of the crop, says Wang. “However, these days, the talent pool inside China is pretty deep.” He notes the success of technology start-up DeepSeek, which has released large-language models that impressed the world, built by a team made up largely of graduates and PhD students at top Chinese universities.

This “broader policy shift underscores a growing emphasis on indigenous innovation and technological self-sufficiency,” says Marina Zhang, who studies innovation with a focus on China at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia.