President Donald Trump’s desire to hit Canada and Mexico with 25 percent tariffs has put a new spotlight on auto manufacturing in the two countries. The two countries have no domestically based automakers of their own, yet they play an integral role in manufacturing for U.S.-based car companies. Sure, right now those tariffs are on hold, but whether they’re actually instituted in a few weeks or some sort of deal is reached to avert them altogether, the landscape of auto manufacturing in the U.S. is going to look a lot different for years to come.

Ties between America’s Big Three automakers – Ford, General Motors and Stellantis – and their neighbors to the north and south date all the way back to the early 1900s, and the relationship has only gotten closer in the decades to follow. Because of this, the Detroit Free Press has decided to take a look at the history of these very special relationships. Here’s more:

[These] ties remained strong throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries. When the automotive industry plummeted into catastrophe during the Great Recession, it wasn’t just the U.S. government that pitched in to preserve it. Canada offered its own tax dollars as part of President Barack Obama’s task force that led General Motors and Chrysler through bankruptcy.

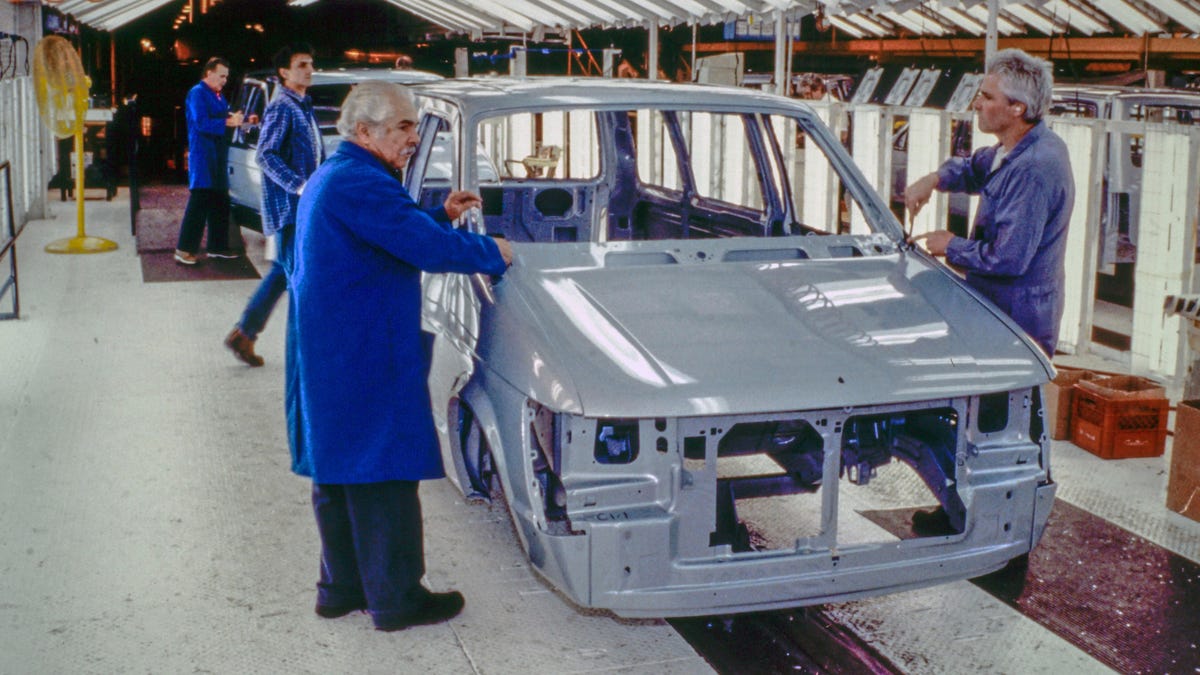

K. Venkatesh Prasad, senior vice president of research at the Center for Automotive Research, said modern vehicle production in Mexico began with components before full-vehicle production was gradually introduced.

K. Venkatesh Prasad, senior vice president of research at the Center for Automotive Research, said modern vehicle production in Mexico began with components before full-vehicle production was gradually introduced.

In Canada, manufacturers started with systems and jumped directly to producing cars, largely due to the proximity of Windsor to Detroit.

“Over the last four years, what you see is the same pattern, a little bit of inversion with how the dollars are being spent, with potentially more growth in money going to Canada than Mexico because of the investments in electrification,” Prasad said.

The U.S.’s ties with Mexican production date back literally 100 years. In 1925, Ford opened up shop in Mexico City and built its first assembly plant there five years later. The 260-person plant built five Model Ts a day. Eventually, production would expand the the Model A, Mercury Cougar and Ford Mustang, Freep reports. General Motors and Chrysler, seeing the advantages of building vehicles in Mexico, soon followed suit. Both would start production there by 1938.

It wasn’t just full automobile manufacturing, either. In the 1960s, automakers from around the world – but especially Japan – started producing parts in Mexico.

Automotive parts production in Mexico flourished in the 1960s with the creation of maquiladoras, foreign manufacturing facilities through which companies can import vehicle parts or assembly products without paying tax. The goal of the duty-free facilities was to encourage international investment in production, while foreign countries like the U.S. and Canada would benefit from cheaper labor.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the influx of Japanese automakers prompted further investment in Mexico, as U.S. automakers sought to offshore labor and cost-intensive production.

The establishment of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 also made it easier for companies to move goods across the continent without paying duties. The revised agreement signed during Trump’s first term still supports this process.

Mexican wages are far lower than those in the U.S., with Mexican autoworkers making roughly about 10% of their northern neighbors today. Nonetheless, Shaiken said, “What I’ve found on the ground in many plants in Mexico is, in fact, Mexican productivity is comparable or even higher than U.S. productivity, and the quality is very high,” he said.

Canada’s story is just about as old as Mexico’s but the workplaces are far different (read: better) because of strong unions in the country. Similarly to Mexico, it started with Henry Ford building his first Canadian automotive plant in 1904. Funny enough, he did this to escape a 35 percent tariff levied on Canadian imports, according to the Free Press.

This lasted until the 1960s, when Canada launched a trade war of its own against the United States after the invention of the automatic transmission, which flooded the Canadian market with vehicles made in Canada, and thus not subject to the tariff. By then, only U.S. companies’ branch plants remained in operation due to the scale and investment the auto industry requires.

In 1965, the Canada–United States Automotive Products Agreement was enacted, a precursor to NAFTA that removed tariffs between the two countries. This led to increased auto manufacturing in Canada and more jobs. The agreement was abolished in 2001, but by then NAFTA had more or less superseded it.

Without the tariffs, Ford, GM and Chrysler were able to kick production into high gear and streamline it in North America. The effects were wild. In 1963, out of the 632,000 vehicles built in Canada, just 921 were exported to the U.S. However, by 1973, Canada built 1,589,000 vehicles, and 1,090,000 of them were exported to the United States, the Detroit Free Press reports.

“For more than 60 years, the Canadian and American auto industries have depended on each other. Together, we build best-in-class cars and trucks that remain the envy of the world,” Unifor National President Lana Payne said in an emailed statement. “Unionized autoworkers fought for and won gold standard collective agreements that created good jobs, raised living standards and built strong, vibrant communities.”

She added: “Two-way trade in automotive goods is about $160 billion per year and split virtually down the middle in near perfect balance. Threatening damage to this relationship, as Trump is doing, threatens good, union jobs on both sides of the border. It is both reckless and dangerous.”