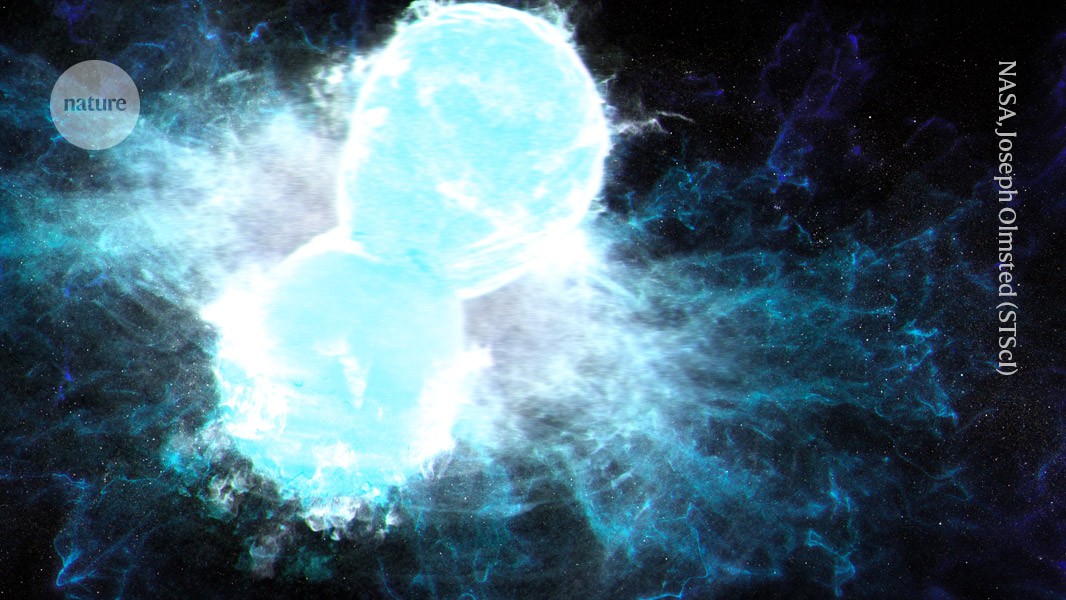

Rarely observed events called kilonovas, produced by the collision of ultra-dense stars, are thought to produce some of the Universe’s heaviest elements.Credit: NASA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

The gargantuan collision of two neutron stars detected with gravitational waves in 2017 sparked one of the largest collective efforts in astronomy, as more than 70 teams scrambled to study its aftermath. Now researchers have devised a machine-learning technique that could trigger such an observing campaign even before the collision occurs — and enable telescopes to watch how stars collide in real time.

Five new ways to catch gravitational waves — and the secrets they’ll reveal

The algorithm was trained on simulations of the data that a gravitational-wave observatory collects in the minutes before two neutron stars merge, which creates a rarely observed event called a kilonova. These events are thought to produce some of the Universe’s heavier elements including gold, platinum and uranium. It would enable such observatories to alert other astronomers that a collision is about to happen at a given time and location in the sky, with 30% more accuracy than existing rapid-response techniques.

“The combination of speed and accuracy in the localization presented in this paper is actually fantastic,” says Mansi Kasliwal, an astrophysicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. The results are described in Nature1 on 5 March.

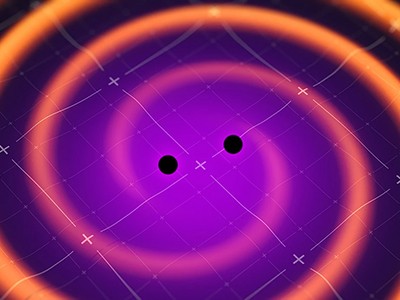

Spiralling stars

Neutron stars are the remnants of massive stars that collapsed at the end of their lifetimes, compressing more than a Sun’s worth of mass into a dense ball of neutrons just 20 kilometres or so across. Occasionally, neutron stars orbit each other in pairs, or binaries. If their orbit is tight enough, the effects of Einstein’s general theory of relativity kick in, and the binary starts to produce gravitational waves — ripples in the shape of space-time. By doing so, the stars lose energy and spiral into each other until they merge.

Researchers have observed only a handful of neutron-star mergers, and only on one occasion — the 2017 event — has the merger also been seen by non-gravitational-wave observatories such as telescopes and γ-ray-burst detectors.