A Year with Gilbert White: The First Great Nature Writer Jenny Uglow Faber & Faber (2025)

The first person to identify harvest mice (Micromys minutus), Gilbert White was an eighteenth-century English curate and naturalist who has been called the ‘father of ecology’. Yet records from his student days show that he was not so much a quiet country gentleman as a lad about town, losing money at cards and buying fancy waistcoats. In her grandly illustrated book A Year with Gilbert White, historian Jenny Uglow looks between these extremes to investigate who White really was.

She depicts a self-taught biologist who not only enjoyed wining and dining, but also took natural history out of stuffy dissecting rooms and into the wild. Spurning the dry descriptions of wildlife commonly used at the time, White’s only book, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1789), brought colourful character to its scientific records of plants and animals. In doing so, it transformed the art of nature writing.

Swarming bees and greedy sheep

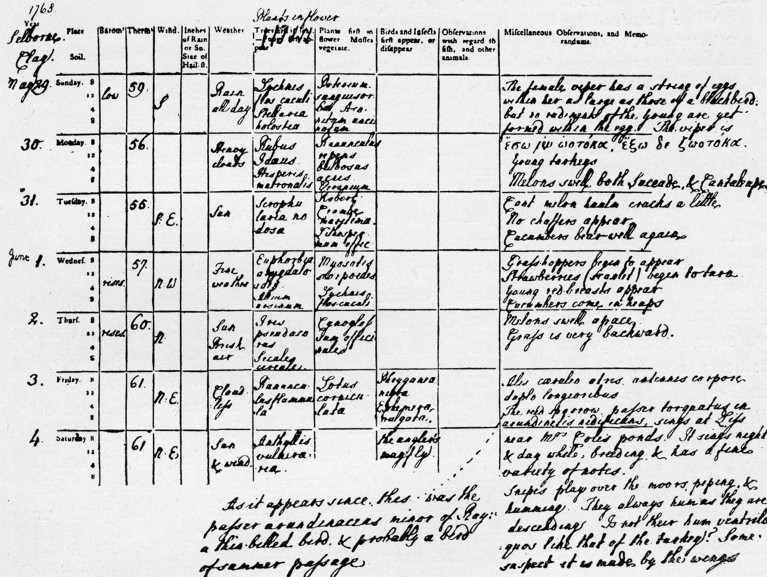

Born in 1720, White was educated at the University of Oxford, UK, before settling at The Wakes — his family home in Selborne, UK — in around 1757. Then, from 1768, he worked for 25 years on his Naturalist’s Journal, a columnar diary in which each page covered a week of observations on fruit and vegetable experiments, local creatures and weather conditions.

White’s daily entries in Selborne were often haiku-like in their simplicity. He described “vast rocklike, distant clouds” or simply stated “Bees swarm much. Sheep are shorn.”

Gilbert White added entries to his Naturalist’s Journal every day for 25 years. Credit: Culture Club/Getty

Uglow’s book examines one year of journal entries, from 1781. She chose this year for two reasons: it was the mid-point in White’s writing of his book, and a year after Timothy the tortoise arrived, a pet inherited by White that was later found to be female. Timothy often featured in the journal entries, being suspected of amorous longings whenever it wandered off.

Uglow compares White’s year in nature with personal sightings at her own home in the Lake District, UK. In January, centuries and miles apart, White logs the chatter of nuthatches (Sitta spp.) while Uglow searches for eelworms (nematodes). Originally, Uglow thought of toadflax (Linaria spp.) as a weed, but White’s delight in its loveliness makes her reconsider. They share a gardener’s irritation with field mice. They each find beauty in autumnal beeches (Fagus spp.). Tulips in both of their gardens are destroyed — White’s by rain, Uglow’s by greedy sheep about whom she jibes, “They have left the daffodils, in disdain”.

Should we treat rivers as living things?

Selborne was not a safe haven for animals, it was a working community. For low-paid labourers, it was a case of human rights over nature’s rites. Birds were routinely shot if they were harmful to crops or livestock. “The air crackles with fear and rage,” writes Uglow, as she relays White’s account of a farmer and his hens tormenting a captured hawk to death.

Uglow also traces the publication of White’s book from its germination to its blossoming. It has remained in print since 1789 and came about when White realized the literary potential of the letters he’d written to fellow naturalists Daines Barrington and Thomas Pennant. For publication, he revised these old letters and added entries from his journals to give an intricate view of Selborne’s natural world. The work inspired a youthful Charles Darwin, who went on a pilgrimage to Selborne in 1857.

But perhaps White’s greatest legacy lies in the chronicling of avian sights and sounds. He kept lists of which birds sang until midsummer and which all year round. Detecting the nocturnal stone-curlew’s cry, he surmised that night-time fliers sent noisy signals to keep their flocks together after dark. Birdsong so obsessed White that he identified three different species of leaf warbler (the chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), wood warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix) and willow warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus)) by their tunes.

Birds from Gilbert White’s journals feature in a stained-glass window in a Selborne church.Credit: RDImages/Epics/Getty