Every summer, Aubree Gordon, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, spends about a month in Managua, Nicaragua, when the rainy season is in full swing. But Gordon is interested in a different kind of season. “June or July can be peak influenza time in Nicaragua,” Gordon says.

Since 2011, she and her colleagues at the Managua site of the Sustainable Sciences Institute, headquartered in Oakland, California, have been tracking flu infections, vaccinations and immune responses in hundreds of children enrolled in the Nicaraguan Pediatric Influenza Cohort study. The work is part of the larger Dissection of Influenza Vaccination and Infection for Childhood Immunity (DIVINCI) study, which is following some 3,000 children in the United States, Nicaragua and New Zealand, most of them from birth. Through the study of antibodies, immune cells and viral genomes, the researchers hope to understand a mysterious feature of the human immune response to the rapidly evolving flu virus.

Nature Spotlight: Influenza

Influenza frequently alters the proteins on its surface, so that over a lifetime, a person encounters many slightly different varieties of the virus. But the immune system generally sticks to what worked before. “Our earliest childhood exposures with influenza viruses prime antibody responses that last a lifetime,” says Scott Hensley, a microbiologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

This phenomenon is known as original antigenic sin (OAS) — antigenic derives from antigen, which refers to any part of a virus to which an antibody binds. The term OAS comes from researchers who, in the 1950s, recognized that most of the flu-binding antibodies circulating in people’s blood match whichever influenza strains were most prevalent during their childhood1.

The emergence of swine and avian influenzas has made it possible to observe OAS in action, owing to it providing protection to people who had been imprinted by similar flu varieties decades earlier. However, it is hard to predict when this bias for ‘retro’ antibodies will help or hamper immune responses to current strains and updated vaccines. Some evidence suggests that the body’s tendency to boost old immune responses to fight off infection might limit its ability to detect parts of the flu virus that have recently changed.

Now, researchers are trying to define the biological basis of OAS and design vaccines that could take advantage of it — or override it to generate immunity against a wider variety of flu strains. Longitudinal studies such as DIVINCI are poised to provide the data to make this possible. “The challenge for vaccinology is understanding how to work better with the memory that’s available,” says Sarah Cobey, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. Yet shifting policies at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the administration of President Donald Trump have created uncertainty about future funding of these studies.

Not so sinful

The benefit of OAS was clearly demonstrated in a 2016 study2 that is often credited with reigniting widespread interest in the phenomenon. In that study, researchers used statistical modelling to correlate people’s birth years with the flu subtype they were most likely to have first been exposed to.

A health-worker takes a swab as part of a long-running flu study in Nicaragua.Credit: Marc-Gregor Camprendon

The most common type of influenza — influenza A — comes in several subtypes named after their surface proteins: haemagglutinin and neuraminidase. These H and N proteins come in different varieties, and influenza subtypes are named after the combination of proteins present. The predominant subtypes over the past 100 years, for example, are H1N1, H2N2 and H3N2. Subtypes that infect people fall into two broad groups based on the haemagglutinin present: group 1 viruses have H1, H2 or H5, and group 2 viruses have H3 or H7.

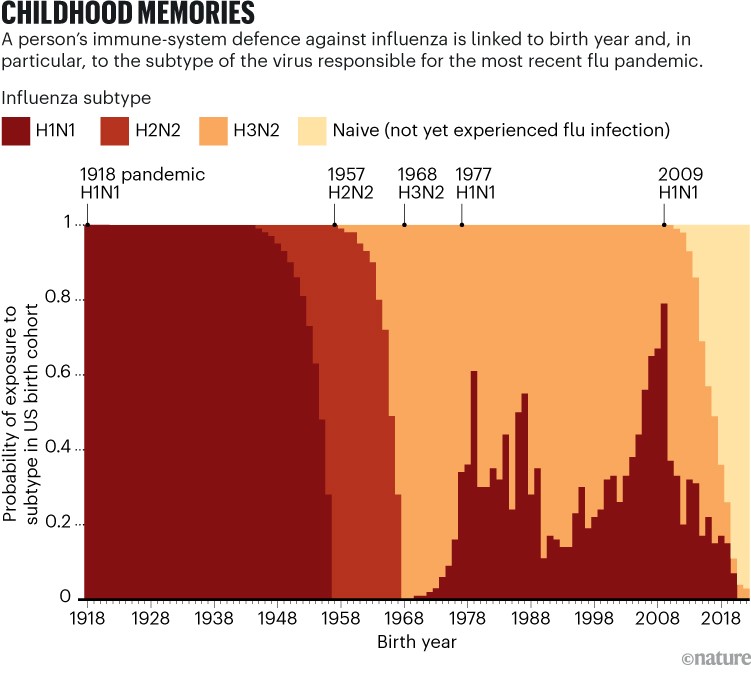

Because most people are exposed to flu by the age of three, Hensley says, “birth year really does serve as a good proxy of what our initial influenza encounters were”. For example, people born between 1918 and 1957 are most likely to have had H1N1 (the cause of the 1918 influenza pandemic) as children (see ‘Childhood memories’).

Source: K. M. Gostic

The researchers in the 2016 study combined this probability data with flu-surveillance data on two avian influenza subtypes that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s — H5N1 and H7N9. They found that people who were probably infected with a group 1 virus in early childhood had the greatest protection against the group 1 virus H5N1 later in life. Likewise, those whose earliest exposure to flu came from a group 2 virus were better protected against the group 2 virus H7N9. The researchers termed this protective effect immune imprinting. Although often used interchangeably with OAS, immune imprinting describes the effect of early-life flu exposure on the entire immune system rather than just on antibody levels.

Several studies have since described the role that antibodies have in the protection that imprinting bestows. Antibodies circulating in the blood can help to block the flu virus from latching onto and infecting cells. In a study published this year3, Cobey, Hensley and their colleagues found that people who were born before 1968 — and therefore probably imprinted with a group 1 virus — carried the highest levels of antibodies that could bind to, block or neutralize a strain of H5N1.

The researchers also examined blood samples collected during clinical trials of an H5N1 vaccine. In older adults, levels of an H5-neutralizing antibody were already high, and the vaccine provided only a slight boost. In children, by contrast, the vaccine brought antibody levels up significantly from a low starting point. The result suggests that in the case of an H5N1 pandemic, public-health officials should prioritize vaccinating children over older adults, Hensley says.

Imprinting studies have tended to focus on the antibody response to influenza A’s haemagglutinin protein. But Hensley, Cobey and their colleagues have described an imprinted antibody response against influenza A’s other surface protein, neuraminidase4. Meanwhile, a team led by immunologist Marios Koutsakos at the University of Melbourne in Australia has shown evidence5 of imprinting affecting the levels of circulating antibodies that target a less common form of influenza: type B.

Things remembered

Circulating antibodies are just one line of defence against flu. Immune cells called B and T cells also remember past infections, and act quickly to protect the body from familiar pathogens. OAS and imprinting are important during this reactivation step.

Cell samples collected in Nicaragua are stored in liquid nitrogen. Credit: Marc-Gregor Camprendon

In 1956, the research team that originally described OAS reported that, after vaccination with one of a variety of influenza A strains, people got a boost of antibodies that stuck to whichever strain they had encountered in childhood6. People still made vaccine-strain-specific antibodies, but usually in lower amounts than their childhood-flu-specific antibodies.

Immunologists now know that this effect results from a combination of normal immune memory and a rapidly mutating virus. Memory B cells remember 3D features of influenza proteins called epitopes. “That is probably the immunological basis of what is called immune imprinting now,” Hensley says.

But influenza’s shifting epitope landscape throws a spanner into this process. Memory B cells might churn out antibodies so efficiently that other, newly exposed B cells miss their chance to engage any new or altered epitopes and form memories. That could be a problem for annual flu shots, which are meant to encourage immunity to new epitopes that appear as a result of viral evolution.

Researchers don’t know the extent to which this competition between naive and memory B cells plays out when people are infected or vaccinated. But animal studies are providing some insight.

In 2023, immunologist Gabriel Victora at the Rockefeller University in New York City and his team showed that memory B cells are more likely to predominate in an immune response when an animal is exposed to two identical or very similar strains in a row7. In mice that were first infected with a flu strain called PR8 and then injected with a PR8 haemagglutinin months later, 90% of the antibodies produced in response to the vaccine came from memory B cells. “Almost everything is dominated by the old memory cells,” Victora says.

However, when the researchers injected previously infected mice with a haemagglutinin that was only 90% identical to that of PR8, the ratio of antibodies from memory B cells and naive B cells dropped to about 50:50. Victora’s team repeated the experiment with several more haemagglutinin proteins that were less similar to the initial infecting strain and found that as the similarity dropped, the proportion of naive B-cell antibodies increased.

The cost of imprinting

Victora’s study suggests that when memory B cells react to a highly familiar flu protein, fewer naive B cells can respond to that protein. “One of the big discussions is whether this is a problem or not,” Victora says.

Which epitopes the imprinted antibodies bind to seems to be a factor. “If that antibody response is targeting something that’s conserved and neutralizing, then perhaps that’s a projective form of imprinting,” Koutsakos says. But if memory B cells and their antibodies target parts of the virus that are not important for infection, the imprint might leave a person less protected.

In 2020, Hensley and Cobey’s groups reported that imprinting with an H3N2 strain that circulated in the 1960s and 1970s might have left middle-aged adults more susceptible to an H3N2 strain that emerged in 20148. The study found that people of all age groups carried antibodies that could bind to the new H3N2, but that those made by middle-aged adults were generally poor at neutralizing the virus in lab experiments.

Even when they don’t prevent infection, antibodies can still help to fight it. Reawakened memory B cells that initially produce poorly binding antibodies can improve with each flu exposure, by acquiring mutations and undergoing a selection process that results in highly specific, tightly binding antibodies, Hensley says.

A memory B-cell arsenal that is too specifically focused on one small feature of a viral protein, however, can become a liability — especially if that feature suddenly mutates. This seems to have happened in the 2013–2014 flu season, when H1N1 dominated. “That season, there was a shift to more and earlier infections in middle-aged adults,” Cobey says. Some people born in the 1960s and 1970s who had an immune response that was imprinted against a focused area on H1N1 were more susceptible to infection by a new strain of H1N1 that had acquired a mutation in that region. There is evidence that the same birth-year cohort in the United States and Canada experienced a dip in vaccine effectiveness during the 2015–2016 flu season, possibly because their immune imprinting made it harder to generate immunity to that year’s vaccine strain.

Longitudinal studies such as DIVINCI could shed light on how imprinting affects flu-vaccine effectiveness, and how annual shots shape flu immunity. The goal is to “describe how these immune responses form and then what their potentials are in downstream infection or vaccine settings,” says Paul Thomas, an immunologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, and one of the study’s principal investigators.