Data availability

This study used an unprecedented dataset comprising monthly observed precipitation series spanning the Mediterranean region, encompassing 27 countries characterized by diverse socioeconomic and administrative profiles. The countries included in this dataset are as follows: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Malta, Egypt, Jordan, Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Cyprus, Turkiye, Moldova, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, the Republic of North Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro, Serbia, Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Italy, France, Spain and Portugal. The data were directly procured from national meteorological or hydrological agencies that actively contributed to this study. In some cases, data were acquired from national research centres collaborating directly with their respective country’s meteorological agency. However, it is noteworthy that meteorological or scientific institutions in Malta, Cyprus and Albania did not respond to our invitations to participate in this study. To ensure coverage for these countries, available precipitation information from continental and global databases—specifically the ECA&D, the GHCN51,52, and in a few cases the Global Surface Summary of the Day (ftp://ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/gsod/)—was incorporated into our dataset.

The dataset comprises a total of 10,238,736 monthly precipitation records derived from 23,609 stations. These monthly records were computed from daily observations, with the strict requirement that no data gaps were permitted in the calculation of monthly totals. Consequently, the dataset represents the aggregation of over 300 million daily precipitation observations collected by rain gauges. The dataset encompasses an extensive temporal range, from 1871 to 2020. However, it is important to note that the temporal coverage exhibits considerable variability. In 1871, a minimum of 117 stations were available, which gradually increased over time to reach a peak of 12,573 stations in 1977. Subsequently, there was a progressive decline, culminating in 6,186 stations by the year 2020 (Extended Data Fig. 1). The spatial coverage also experienced significant transformations. Initially, the stations were concentrated primarily in the north-western part of the region. However, from 1901 onwards, there was a marked expansion of station coverage in most countries, leading to a high density of stations after 1931 (Extended Data Fig. 2). These fluctuations in spatial and temporal coverage are attributed to the historical development of meteorological networks in various countries, influenced by the establishment of national meteorological services, historical and international conflicts, and divergent digitization efforts by national meteorological services.

Our investigation necessitated the use of restricted data sources to achieve our research objectives comprehensively because previous studies in this area have often been limited by datasets that are either spatially or temporally constrained. These limitations have contributed to an incomplete understanding of precipitation patterns within the region. Publicly accessible global and continental databases contain significantly fewer series compared to those held by meteorological services (Supplementary Fig. 30), failing to capture the considerable variability in precipitation characteristics of the Mediterranean region.

Our access to restricted data aimed to address these gaps, offering a more comprehensive analysis of precipitation variability and trends in the Mediterranean. All available raw data from the different Mediterranean countries were accessible for the analysis. However, its sharing and/or redistribution was subject to the specific policies of each country (Extended Data Fig. 3). Several countries, including Croatia, Egypt, France, Israel, Moldova, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain and Syria, provided all available raw precipitation data, while Greece and Italy supplied a subset from their stations. This data is available in the following repository: https://zenodo.org/records/12607467. Details regarding the data availability and sharing policies for countries that either did not provide raw data or restricted redistribution can be found in a supplementary Excel file.

We developed and distributed data processing software to national meteorological services and research institutions, with the aim of balancing respect for data privacy concerns with the need for comprehensive analysis. This approach facilitated standardized data processing and maximized the use of available data within the constraints of national data policies, representing a pragmatic solution for conducting a robust climate study in an area with restricted data access.

The developed software was used with the data from the countries that provided information for free, and was distributed to and used by participants from the countries involved in the study who could not share their data given their restricted data-sharing policies. The primary purpose was to process raw monthly precipitation series by conducting various data quality control procedures, a gap-filling process, performing a homogeneity test and rectifying data inhomogeneities. Subsequently, the software was employed to execute the statistical tests, yielding the results presented in this study. The same procedure was applied to the series available from the GHCN and ECA&D databases to replicate the analysis using the currently available data in these public databases.

These tasks were performed by the national teams that could not share their data. To enhance accessibility and replicability, the results for individual countries have been made available as separate files in a public repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10022617). The repository also contains regional precipitation series for the entire Mediterranean region, along with detailed information on the file contents and an example script for accessing and reading the data.

Precipitation quality control and reconstruction

During the quality control phase, precipitation series with durations of less than 10 years were excluded from the analysis. For the remaining series (18,140), each monthly observation was subjected to a comparison with corresponding values from neighbouring stations, after transforming each time series into their empirical quantiles53. Observations that exhibited differences in excess of 0.8 units from the average quantiles of the five closest stations within a 200-km radius were flagged as suspicious and subsequently discarded. In addition, the quality control process involved the assessment of chains of zero values. Specifically, all chains comprising more than five consecutive months with zero precipitation were eliminated from the dataset if any of the months in the chain had less than 70% of zero values. Chains of more than eight consecutive months with zero precipitation were also removed unless they encompassed the summer season, during which zero precipitation is a plausible occurrence in the region. The quality control process was applied to 9,997,914 records, resulting in the removal of 23,239 suspicious records—equivalent to 0.23% of the total data. Most of the series showed a percentage of removed records at or near 0% (Supplementary Fig. 31).

An inherent challenge in observational datasets covering extensive time periods, as was the case with the dataset developed for this study, is the fragmented nature of most precipitation series. It is a common occurrence for older observatories to cease operations while new ones are established throughout the extensive time frame under consideration54,55,56. To address this issue, a data reconstruction process was developed. Its purpose was to bridge the gaps in the dataset and generate continuous series of uniform length, free from data gaps.

To address data gaps, we adopted a procedure consisting of filling each gap with the observation from the nearest neighbouring station, after rescaling the records from the neighbouring series to align with those of the candidate series while preserving the temporal variance57,58. The selection of neighbouring series was guided by both correlation and distance criteria, requiring a minimum correlation coefficient of 0.7 and a maximum distance of 200 km. Also, a minimum overlapping period of 15 years between both time series was required to correct the bias between them. This approach aligns with previous studies that employed a similar methodology54,55,57.

To mitigate potential biases and variance differences between the two series (the one undergoing reconstruction and its neighbouring counterpart), the precipitation records were subject to standardization, using data from their overlapping time periods. Notably, precipitation series do not adhere to a normal distribution59. Therefore, standardization involved selection from a range of skewed, positive-valued distributions, which included gamma, exponential, general extreme value, generalized logistic, generalized Pareto, generalized normal, lognormal, Pearson type III and Weibull distributions. These distributions are widely employed in the analysis of hydroclimatic data60,61,62,63,64.

For each station and month of the year, the distribution was selected on the basis of the distribution that yielded the highest P-value of the Shapiro–Wilks normality test after standardization63, ensuring the normality of the standardized series. It is noteworthy that, due to the unique characteristics of Mediterranean precipitation, certain monthly series could not be effectively fitted to any of the candidate distributions, particularly during the summer season in regions where the majority of records registered zero precipitation. These specific series were treated individually and reconstructed by directly utilizing the precipitation values from the neighbouring series, adjusted according to the monthly long-term ratio between the candidate series and the neighbouring region.

The standardized values from neighbouring stations were converted into cumulative probabilities, denoted as P(X) = p(x ≤ X), and subsequently employed to fill gaps in the dataset of the target station. This iterative procedure began with the closest neighbouring station and extended to progressively more-distant ones, adhering to the previous criteria. To restore the inputted values to their original magnitudes (measured in millimetres), quantiles corresponding to their cumulative probabilities were computed using the data of the target station. As an exception to this procedure, instances where a value of zero precipitation existed in the neighbouring series led to the direct incorporation of such zero values into the dataset of the target station.

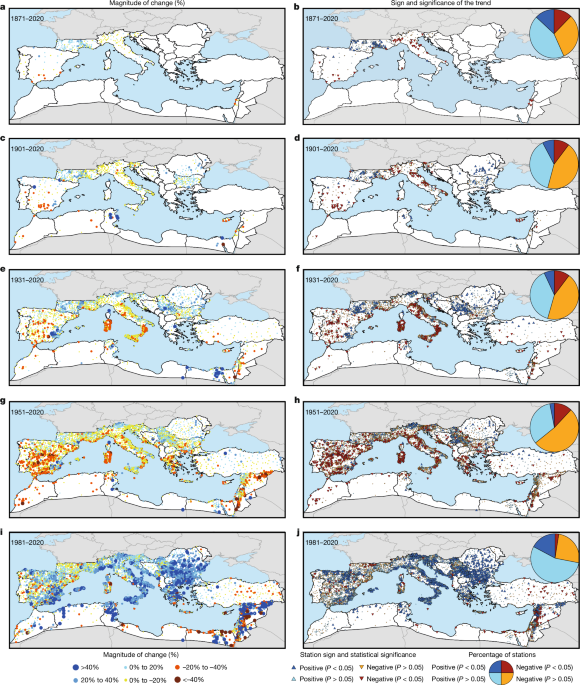

We established five distinct datasets based on the following time frames: 1871–2020, 1901–2020, 1931–2020, 1951–2020 and 1981–2020. Within each period of analysis, we exclusively retained series that had at least 75% of their original records fall within the specified time period and that showed no data gaps after reconstruction. However, a small percentage of series that did not meet the 75% threshold for some periods were retained for analysis during those particular periods. This was done because they met the 75% requirement in earlier periods and were necessary to maintain continuity in the analysis across different time frames. Consequently, the number of stations in each set varied accordingly.

As an exception, stations with data gaps accounting for less than 5% of the corresponding time frame were subjected to a secondary reconstruction process. During this process, we relaxed the conditions for auxiliary stations to possess a correlation coefficient (r) exceeding 0.5, with no distance restrictions at the country level. This relaxation allowed for the inclusion of additional series in each respective set. Series that could not be fully reconstructed were eliminated.

Finally, in the case of Libya, where it was not possible to obtain a significant number of complete series, even using the procedure described above, we permitted data gaps of up to 3 years. However, these gaps were subject to the condition that they did not occur within the first or last 5 years of the series, so as not to unduly impact trend analysis. To address these gaps, we employed a strategy of filling them with the 3-year precipitation average from the periods immediately preceding and following the gap.

Most of the series used in our study across various periods have low percentages of reconstructed data (Extended Data Fig. 4), indicating that the analysed series predominantly consist of a high percentage of original data. The number of data gaps filled in the series retained for analysis varies across different periods. However, the percentage of reconstructed data in each series was minimal. The average percentage of reconstructed data across the series for the different periods is as follows: 1871–2020, 11.07%; 1901–2020, 12.42%; 1931–2020, 12.40%; 1951–2020, 10.68%; and 1981–2020, 11.06%. Moreover, there is no significant spatial bias in the percentage of reconstructed data in the series retained for analysis in each period (Supplementary Fig. 32). In the most recent period (1981–2020), some series were used with less than 75% original data, particularly from Tunisia, Italy, Libya and Bosnia–Herzegovina. In these regions, recent conflicts or changes in the management of meteorological networks had led to interruptions in data recording or significant data gaps in the series. Despite these challenges, our conservative data reconstruction approach ensured that the resulting series remained of high quality, with the majority of the original data being preserved in the final analysis.

Our methodology not only filled gaps in the time series, but also modelled the observed precipitation records using data from neighbouring stations—that is, missing data were statistically hindcasted. This approach facilitated the evaluation of reconstruction quality through comparisons between observed and reconstructed series. Monthly reconstructions from each station exhibited a remarkably high level of agreement between the observed and reconstructed precipitation, a relationship assessed using the agreement index65 (Extended Data Fig. 5). Comparing the available observed and reconstructed data revealed widespread agreement, with the majority of records exhibiting a near-perfect match between observed and modelled precipitation records, irrespective of the season (Extended Data Fig. 6). Importantly, this reconstruction is not influenced by data availability. Even for the 1871–1900 period, during which fewer neighbouring series were available, the reconstruction maintained a comparable level of quality (Supplementary Fig. 33). Moreover, this consistency is not impacted by seasonality.

Precipitation homogeneity

After reconstructing the series, we subjected them to a rigorous homogeneity testing process to identify any potentially suspicious temporal deviations. For each of the 12-monthly series, homogeneity testing was conducted against an independent reference series. Reference series were constructed as the average of the five neighbouring series that were best correlated with the series of the target station, after which all of them were transformed to difference series66. Subsequently, the standard normal homogeneity test was employed to identify potential rupture points indicative of inhomogeneities67. In the cases where these inhomogeneities displayed a P value less than 0.1, they were considered acceptable and subsequently corrected. In such instances, the affected series were split at the detected rupture point, and the oldest of the two subsets was corrected by multiplying it by the ratio between the average values of the records before and after the rupture point68. This procedure was repeated for each series until no more inhomogeneities were identified. The homogeneity assessment was initially performed for the series commencing in 1871, and subsequently for those starting in 1901, 1931, 1951 and 1981. Notably, once a series had been corrected for a specific period, it was not subjected to homogeneity testing in subsequent periods, thereby ensuring that a single station did not exhibit different records across the five distinct sets. The number of inhomogeneities identified and subsequently corrected varies from one country to another, contingent upon the quality of the available data. Nonetheless, with the exception of Egypt and Syria, the original data series, on the whole, displayed high temporal quality (Supplementary Table 4). Importantly, the impact of data homogenization on the assessment of precipitation trends was minor. This is evident in the very high spatial agreement between annual precipitation trends (in percent) using the series before and after the homogenization process for different periods. The homogenization process did correct a small number of series affected by problems, but it did not alter the magnitude and spatial trend pattern (Supplementary Fig. 34).

The aforementioned process allowed us to obtain a quality controlled, reconstructed and homogenized dataset, encompassing 307 series, for the period 1871–2020—912 for 1901–2020, 2,908 for 1931–2020, 5,441 for 1951–2020 and 7,151 for 1981–2020. The generated number of series significantly surpasses those derived from the precipitation data available in publicly accessible global and continental databases (Supplementary Table 5). National average series were compiled from all the available stations within each of the five selected analysis time frames. To create a comprehensive regional overview, global average time series were subsequently derived for the entire Mediterranean region. This entailed computing an area-weighted average, where each country’s contribution was weighted proportionally according to its surface area. This process ensured a robust representation of regional precipitation dynamics.

Furthermore, we computed the SPI59 at a three-month time scale for each station across the five analysis periods. These calculations aimed to assess potential changes in meteorological drought occurrence and intensity. We identified meteorological drought episodes by evaluating sequences of consecutive negative SPI values. For each of these episodes, we determined both their duration and magnitude, adhering to established protocols for drought characterization69,70.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of precipitation changes across the available series for different time periods was conducted using the nonparametric Mann–Kendall test, which assesses both the trend signal and its statistical significance. Notably, the Mann–Kendall test is nonparametric in nature and does not rely on any specific underlying probability distribution of the data. It offers robustness against outlier data, making it a suitable choice for our analysis. As a preliminary step, we applied pre-whitening to the series before conducting the test71,72.

To evaluate the magnitude of precipitation change, we employed the nonparametric Theil–Sen (TS) regression. The TS slope estimator provides insights into the temporal rate of change, quantifying how precipitation evolves over time (that is, precipitation change per year). Higher slope values indicate more rapid changes in precipitation. Importantly, we expressed the rate of change in terms of relative percent change per year with respect to the TS regression intercept, rather than absolute values in millimetres. This approach enhances the spatial comparability of different stations located in regions with substantially varying precipitation values.

When examining precipitation trends on a seasonal basis, we adhered to the delineation of boreal seasons, including winter (December–February, DJF), spring (March–May, MAM), summer (June–August, JJA) and autumn (September–November, SON).

To ensure a robust assessment of precipitation trends, accounting for the sensitivity of these trends to variations in the study period’s length and selection73, we conducted a systematic analysis encompassing all feasible temporal frames of 30 years or more within each of the four study periods. The results were visually summarized using heatmaps, which illustrate both the magnitude of change and its statistical significance.

Due to the substantial number of stations and time frames, summarizing the heatmaps required the application of principal component analysis in S-mode74. This approach enabled the identification of regions exhibiting similar patterns in temporal trends as represented by the heatmaps. In total, we obtained five components for each period starting in 1901, 1931 and 1951 on an annual scale, as well as for each of the four seasons, resulting in a total of 15 components both annually (Supplementary Fig. 1) and seasonally (Supplementary Figs. 7–10). These components were expressed in the same units as the original variables, representing the percentage change in precipitation per year. The weights assigned to each component at each station were also used to calculate the corresponding P values for each component. By mapping the component loadings, we determined the geographical areas where each heat map component was most representative.

Atmospheric circulation indices

To disentangle the influence of natural climate variability and other atmospheric forcing mechanisms from the precipitation dynamics of the entire Mediterranean region, we employed a stepwise regression approach75. Details about the methodological approach are provided in Supplementary Information section 3.2. We considered the annual and seasonal precipitation averaged over the Mediterranean region as dependent variables and two large-scale atmospheric circulation indices as independent variables22,76. These indices were the NAO13 and the MO77 (details in Supplementary Information section 3.3). We purposely excluded other atmospheric mechanisms, such as the Indian Ocean Dipole78, which impacts precipitation in the Eastern Mediterranean, due to the limited availability of reliable long-term time series16. The two selected indices exhibit stationarity over the long term, and their recent dynamics are mostly associated with the internal climate variability (Supplementary Information section 3.1). In addition to the large-scale circulation indices, we utilized regional atmospheric circulation indices, focusing on storm frequency and the occurrence of blocks and ridges impacting the Mediterranean region. Methodological details for calculating these metrics are provided in Supplementary Information section 3.4. The NAO and MO were correlated with the dynamics of these regional drivers (Supplementary Information section 3.5), although they exhibit independent capacities to model precipitation during the cold season.

In our analysis, we focused on the four distinct periods commencing in 1901, 1931, 1951 and 1981. Following the model fitting process (Supplementary Information section 3.2), we examined the trends of the residuals, representing the disparities between the modelled and observed precipitation values. This step aimed to determine whether the observed precipitation trends could be explained by atmospheric dynamics (in which case the residuals would lack a statistically significant trend) or if they were influenced by other factors (indicated by statistically significant trends in the model residuals). We employed the t-statistic to assess the role of each circulation index in explaining precipitation variability.

Climate model simulations

We conducted a comparative analysis of the long-term precipitation trends observed across the Mediterranean region and those derived from climate model simulations over corresponding time frames. The primary objective of this assessment was to evaluate the consistency of model simulations in relation to observational data, rather than attributing trends to anthropogenic factors.

Our comparison encompassed five distinct analysis periods and involved historical simulations from both the CMIP579 and CMIP680 experiments. Despite the improvements in model physics, parametrization and spatial resolution in CMIP6, signifying potentially more reliable results in this iteration, we decided to include both the CMIP5 and CMIP6 experiments to ensure a more comprehensive evaluation.

For CMIP5, we utilized precipitation data from 47 models representing the historical experiment spanning from 1860 to 2005, as well as the Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 experiment covering the period from 2006 to 2020. In the case of CMIP6, we employed data from 25 models for the historical experiment, ranging from 1850 to 2014, and the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 experiment spanning from 2015 to 2020 (Supplementary Table 6).

The choice of Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (CMIP5) and Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (CMIP6) scenarios was based on their alignment with observed CO2 concentrations for the considered years. Rather than relying solely on the ensemble mean of each CMIP experiment, we incorporated the complete range of individual model simulations. This approach enabled us to account for the uncertainties inherent in a multi-model ensemble.

Supplementary Fig. 35 provides a comprehensive overview of the methodological approach employed in this study. It encompasses various aspects, including data processing and temporal analysis.