Malaria remains a major public health concern, with many African nations being far from meeting their malaria elimination targets4,5. Vector control methods including indoor residual spraying and long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets have played a pivotal role in reducing malaria incidence, but the emergence of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes has impeded further progress6. In addition, Africa’s rapidly growing population and persistent malaria receptivity make these interventions increasingly unsustainable as standalone solutions. This highlights the urgent need for innovative, self-sustaining and cost-effective technologies to complement existing efforts in malaria elimination. Gene drive technology, which enables the biased inheritance of selected traits and can spread through populations at rates exceeding those predicted by Mendelian genetics, has emerged as a promising new paradigm7,8.

Gene drive can offer a transformative solution for malaria elimination by spreading genetic modifications that can either suppress mosquito populations or render them unable to transmit the disease2,9,10. Our work focuses on the latter approach known as mosquito population modification or replacement, whereby antiparasitic effectors introduced into the mosquito genome are spread to fixation within populations using a Cas9 endonuclease-based synthetic gene drive. In our design, the transmission-blocking effector and gene drive functions are separated into distinct genetic traits and strains3,11,12,13. This separation offers several advantages: it allows the development, testing and optimization of effector constructs in endemic settings independently of a full gene drive system; it facilitates rigorous risk assessment and community engagement before introducing self-propagating elements and it provides a safer, more modular pathway towards deployment12. Crucially, evaluating non-autonomous effector strains helps address elevated regulatory and containment requirements associated with autonomous gene drive systems.

Genetic modification of mosquitoes to reduce their vectorial capacity was first attempted more than two decades ago, and dozens of transgenic strains have been described in the literature to date9,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, no effector has ever been evaluated against parasites other than laboratory strains many of which were established in the early 1980s31. For this reason, their propensity to block the transmission of genetically diverse Plasmodium isolates now in circulation is unknown.

We previously demonstrated the efficacy of one such A. gambiae effector modification in inhibiting the NF54 strain of laboratory-cultured P. falciparum. This modification, termed MM-CP, involves two antimicrobial peptides, magainin 2 from the African clawed frog and melittin from the European honeybee32, integrated into and expressed from within the endogenous zinc carboxypeptidase A1 gene (CP)33. This minimal genetic modification that harbours no fluorescent markers interferes with oocyst development causing a significant delay in the release of infectious sporozoites. It also reduces the lifespan of homozygous female mosquitoes, further minimizing their potential to transmit malaria. Predictive models suggest that gene-drive-mediated population-wide propagation of MM-CP could disrupt disease transmission across various settings, offering promise for malaria elimination even in scenarios in which resistance to the effector or the drive eventually emerge. Here we adapted this technology for an African context to evaluate its ability to suppress P. falciparum parasites naturally circulating among humans.

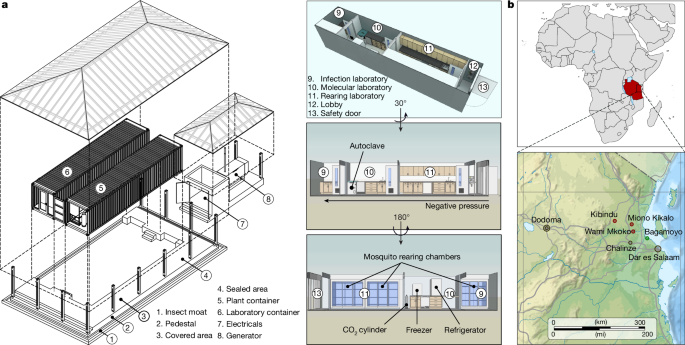

The implementation of gene drive technologies in malaria-endemic regions faces substantial challenges, including limited access to appropriate containment infrastructure, regulatory uncertainty, insufficient local capacity for genetic engineering and biosafety, and the imperative for community trust and public transparency. To enable our work, we developed an integrated Modular Portable Laboratory and Containment Level 3 (MPL/CL3) insectary facility, specifically designed for generating, housing and studying genetically modified mosquitoes within an African context (Fig. 1a). The MPL/CL3 was designed to address some of these constraints by offering a high-security and standardized facility tailored to local environmental and regulatory conditions. It incorporates climate and illumination control systems, rearing chambers, microbiologically safety cabinets, water management and waste disposal systems, an autoclaving unit and a fully equipped laboratory. The facility was constructed within two intermodal shipping containers in Spain and transported and installed at the Bagamoyo campus of the Ifakara Health Institute (IHI) in Tanzania (Fig. 1b). By embedding cutting-edge vector biology capacity within endemic settings, the MPL/CL3 supported local research leadership, regulatory readiness and public engagement, laying essential groundwork for responsible development and evaluation of gene drive technologies. Detailed specifications and technical plans are presented in the Methods and Supplementary Note. All protocols involving the generation and study of transgenic mosquitoes were reviewed and approved by the relevant institutional and national regulatory authorities in Tanzania.

a, Integrated MPL/CL3 facility. Architectural design plans for the (left) and a detailed view of the integrated laboratory and insectary container unit (right) are shown. The laboratory comprises a lobby, an incubator room for mosquito husbandry, a molecular biology laboratory and a dedicated space for P. falciparum DMFAs and housing of infected mosquitoes. The second container unit houses systems that regulate and maintain optimal environmental conditions, including a negative pressure system for biosecurity, water purification and waste treatment. An external electricity generator supports these operations. b, Field sites for parasitological surveys and gametocyte carrier recruitment. Locations of villages in the Pwani region where parasitological surveys were conducted in children are shown in relation to the IHI Bagamoyo campus (housing the MPL/CL3 facility), the capital Dodoma, the major port city Dar es Salaam and the town of Chalinze, where meteorological data were recorded. The map is modified to highlight sites mentioned in the paper. Tanzania road map in b adapted from OnTheWorldMap.com (https://ontheworldmap.com/tanzania/tanzania-road-map.html).

The first A. gambiae transgenic line developed onsite within the MPL/CL3, named zpg-CC, was designed to streamline all transgenesis processes by expressing both Cre recombinase and Cas9 endonuclease under the control of the zero-population growth (zpg) gene promoter. This dual helper strain enables the efficient removal of sequences such as transgenesis markers flanked by loxP sites and establishment of transgene homozygosity through homing. The initial development and characterization of the zpg-CC line were conducted at Imperial, before the line was recreated in Tanzania.

The zpg-CC construct includes a dominant DsRed transgenesis marker, integrated into the kynurenine hydroxylase (kh) gene locus (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Disruption of both copies of the gene results in white-eyed mosquitoes, serving as a recessive phenotypic marker. Although the zpg-CC helper line was robust and fertile, it showed reduced overall fitness, probably due to the disruption of the kh locus and/or the effects of germline-specific or leaky expression of both Cre and Cas9. Compared with wild-type (wt) females, sugar-fed transgenic homozygous zpg-CC females showed a small decline in survival over time (Extended Data Fig. 1b), consistent with previous observations in other mosquitoes34,35. They also laid significantly fewer eggs after blood feeding, with a lower proportion hatching, indicating a reduction in reproductive fitness (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

To assess the efficiency of the zpg-CC helper line in inducing homing when combined with a non-autonomously driveable transgene expressing guide RNA (gRNA), we crossed heterozygous zpg-CC males with females of a previously generated CP knockout (CP-KO) line that harbour a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression cassette and a gRNA expression module inserted within and targeting the CP gene36 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Heterozygous offspring expressing both GFP and DsRed were sib-mated, and the resulting larvae were screened for green fluorescence. All 623 larvae screened were GFP positive, compared with the 75% expected from a Mendelian intercross of hemizygotes. This indicates 100% Cas9-mediated homing, induced by Cas9 provided by the zpg-CC helper line (Extended Data Fig. 1d).

Next, we assessed the capacity of the zpg-CC helper line to excise a loxP-flanked GFP expression cassette through the expression of Cre recombinase. As a tester line we used the zpg-Cas9GFP strain, in which a Cas9 coding sequence was inserted within the zpg gene to encode Cas9 linked to the zpg C terminus through an E2A ribosome-skipping peptide sequence. An intron harbouring the excisable GFP expression cassette flanked by loxP sites and a gRNA module is located within the E2A sequence (Extended Data Fig. 1a). We crossed zpg-Cas9GFP males with heterozygous zpg-CC females, selecting GFP and DsRed positive males for subsequent crosses with wt females (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Among 417 offspring larvae, only 13 showed green fluorescence, indicating efficient Cre-mediated excision of the GFP cassette (97%).

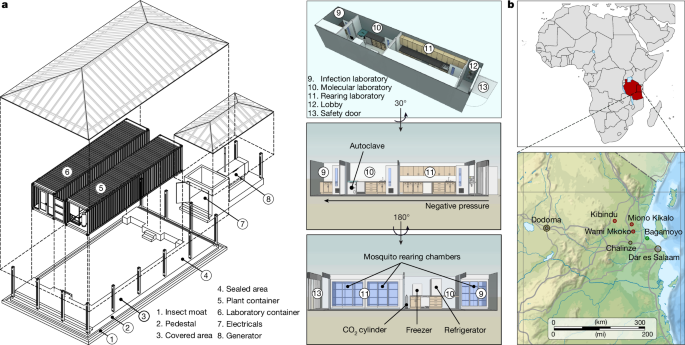

These experiments confirmed efficient Cas9 and Cre expression by the zpg-CC helper strain. We therefore recreated the zpg-CC line in Tanzania, by microinjecting embryos of the A. gambiae Ifakara strain37 with the zpg-CC plasmid together with independent Cas9 and gRNA helper plasmids. G0 larvae showing transient fluorescence were allowed to mature into adults that were then crossed with wt mosquitoes in separate male and female crosses (Fig. 2). These crosses produced 28 G1 transgenic larvae expressing DsRed in the nervous tissue, of which 25 (16 males, 9 females) reached adulthood. After four rounds of backcrossing with wt mosquitoes, a pure and stable colony was established by continuously selecting larvae showing DsRed fluorescence and kh locus disruption, indicated by the absence of eye pigments. Despite Cas9 expression, these mosquitoes cannot autonomously propagate their modification through gene drive, as they lack genomic integration of a gRNA gene.

This approach involved a series of breeding and selection steps, detailed as follows in a clockwise progression. Top left, tabular summary of the processes for generating the zpg-CC and MM-CPGFP transgenic lines. Top middle, each transgenic line was outcrossed with the wt Ifakara strain to enhance line vigour. Top right, strains were maintained through sibling mass crossing to preserve genetic stability. Bottom right, MM-CPGFP females were crossed with zpg-CC males, and double-positive individuals (GFP and DsRed) were selected and mass-bred. Bottom middle, this process enabled Cre-mediated removal of the GFP expression cassette (floxing) and Cas9-driven homozygosity of the MM-CP transgene (homing). Bottom left, non-fluorescent individuals were selected for pupal case genotyping to identify homozygous MM-CP individuals. These homozygous mosquitoes were then mass-bred to establish the MM-CP line, subsequently used in homing and P. falciparum DMFA infection assays. eGFP, enhanced GFP.

Next, we generated the MM-CP line by microinjecting A. gambiae wt Ifakara embryos with the MMGFP-CP plasmid, containing a gRNA for integration into the CP locus and a Cas9 source38. This resulted in a single G1 transgenic male expressing GFP in the eyes and ganglia, which was then backcrossed with wt mosquitoes for four generations to establish a stable MMGFP-CP precursor line (Fig. 2). To achieve transgene homozygosity and remove the GFP marker cassette, MMGFP-CP females were crossed with zpg-CC males and double fluorescent progeny were sib-mated. The resulting colony carried the antimalarial MM-CP transgene as a minimal, markerless modification. Molecular genotyping confirmed that most mosquitoes in the colony were homozygous for the transgene (Fig. 2).

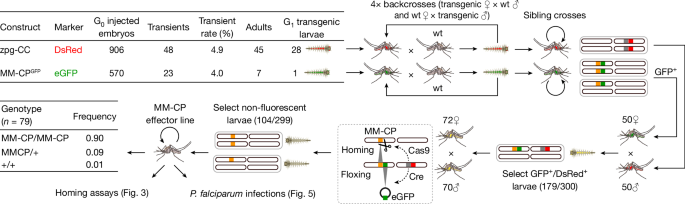

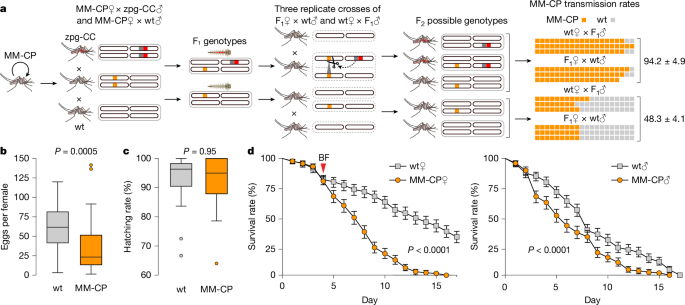

To quantify MM-CP inheritance rates in the presence of Cas9, we crossed MM-CP females with zpg-CC males (which express Cas9) and vice versa (Fig. 3a). Equivalent crosses with wt mosquitoes served as controls. The resulting F1 zpg-CC;MM-CP and +;MM-CP heterozygotes from these experimental crosses were then separately crossed with wt mosquitoes, with male and female G1 individuals crossed independently. We conducted three replicates for each cross and genotyped 20 F2 progeny per replicate to assess the presence of the MM-CP transgene in a heterozygous state (Extended Data Table 1). Both male and female MM-CP;zpg-CC crosses with wt mosquitoes showed high inheritance rates of the MM-CP transgene to F2 progeny, averaging 94.2 ± 4.9%, compared with the control crosses (MM-CP females crossed to wt males), which showed near-Mendelian segregation at 48.3 ± 4.1% (Fig. 3a). These results indicate high rates of non-autonomous gene drive of the MM-CP transgene when combined with germline Cas9 expression.

a, Schematic of the non-autonomous homing assay used to evaluate transmission efficiency of the MM-CP transgene. Homozygous MM-CP females were crossed with either zpg-CC males (Cas9 source) or wt Ifakara males (control). F1 progeny were sexed and reciprocally crossed with wt Ifakara mosquitoes. Twenty F2 progeny per cross (in triplicate) were genotyped by PCR to detect the MM-CP transgene. The bar graph (far right) shows inheritance rates, with significantly higher MM-CP transmission in zpg-CC crosses, confirming efficient non-autonomous homing. Each row represents a biological replicate, and each box denotes one mosquito (5% rate). Note that only 17 mosquitoes were genotyped in 1 replicate. b, Fecundity of MM-CP (n = 23 and 25) and wt (n = 25 and 24) females, measured as the number of eggs laid per mosquito in two independent biological replicates. MM-CP females showed significantly reduced egg output compared with wt controls (P = 0.0005, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test). Boxplots show median, interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles) and full data range (whiskers) for each group; dots outside boxplots are outliers. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 1. c, Mean fertility of female mosquitoes used for the fecundity assays (b), measured as hatching rate (% of eggs developing into larvae), did not differ significantly between lines (P = 0.95, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test). Error bars show the range of fertility rates across the two replicates. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 1. d, Survival curves postemergence. Left, females post-bloodmeal (BF); right, sugar-fed males. MM-CP females showed markedly reduced survival after blood feeding (P < 0.0001, log-rank test); males also showed reduced survival under sugar-only conditions (P < 0.0001), although to a lesser extent. Data points represent the mean of two independent biological replicates (MM-CP, n = 378 and 242; wt, n = 368 and 350), each comprising three cages of mosquitoes reared from separate aquatic trays. Error bars indicate the range between replicates. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 2.

MM-CP mosquitoes originally generated in a mixed KIL/G3 genetic background showed reduced fitness, including lower fecundity and decreased survival, particularly in females38. KIL and G3 are two genetically distinct A. gambiae laboratory strains colonized from northern Tanzania and The Gambia in the 1970s, respectively. Life history assays with the new MM-CP line in the A. gambiae Ifakara background yielded similar results, confirming that these phenotypes are consistent across genetic backgrounds, an important consideration for gene drive deployment. Specifically, MM-CP females laid significantly fewer eggs than controls (Fig. 3b), although hatching rates were comparable (Fig. 3c). Survival was reduced in both sexes, with the most pronounced effect observed in females following a bloodmeal (Fig. 3d). Although some survival effects may reflect inbreeding from the transgenesis process and are unlikely to persist under gene drive conditions involving continuous outcrossing, the sharp post-bloodmeal decline in female survival is probably driven by strong antimicrobial peptide expression at the bloodmeal-inducible CP locus or perturbations of CP expression due to the antimicrobial peptide integration. This phenotype is modelled to enhance the efficacy of the intervention by reducing the likelihood that infected females survive long enough to transmit the disease38. Despite these fitness costs, multi-generational cage experiments have demonstrated that MM-CP can still be driven efficiently to near-fixation when combined with a self-propagating Cas9 source, supporting the robustness of MM-CP under gene drive rconditions39.

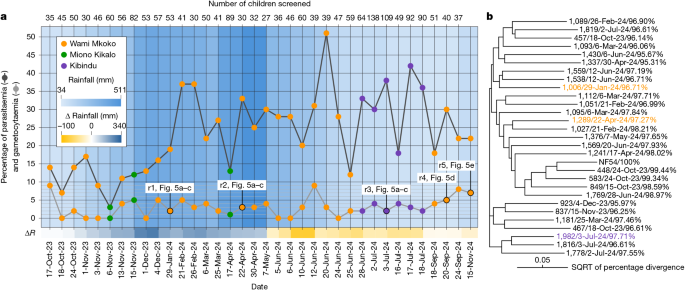

Next, we proceeded to assess the efficacy of the locally developed MM-CP strain in inhibiting parasites circulating among infected children. We conducted surveys in primary school pupils in Wami Mkoko and Miono Kikalo villages to determine the levels of parasitaemia and gametocytaemia (Fig. 2b). These surveys were later expanded to include children aged 6–14 in Kibindu village. Malaria infection was determined using rapid diagnostic testing (RDT), with parasites quantified through thick blood smear microscopy. Written informed consents were obtained from parents or guardians, and oral assent was secured from children. These activities were conducted alongside structured community engagement to promote transparency, address concerns and foster public trust. The results indicated year-round malaria transmission, with parasitaemia and gametocytaemia present in roughly 25–30% and 2–5% of screened children, respectively (Fig. 4a). The high malaria prevalence throughout the survey period may be linked to the 2023–2024 El Niño-Southern Oscillation that occurred between July 2023 and April 2024 and was associated with significantly more rainfall in this part of the country40. To ensure that a diverse array of parasite genotypes were circulating in these three villages, we sequenced four genes (CSP, AMA1, SERA2 and TRAP) known to provide a robust measure of P. falciparum diversity41. The results confirmed that our sampling strategy captured a representative diversity of genotypes in these communities (Fig. 4b).

a, Epidemiological data on P. falciparum parasitaemia and gametocytaemia among children in three villages within the Pwani region. The bottom x axis indicates screening dates, the top x axis indicates the number of children screened each day, and the y axis shows the percentage of parasitaemic and percentage of gametocytaemic children among the total number of children screened on each date. The total number of children screened per date is shown above the graph. Dates when gametocytaemic blood samples (one per date) were used for successful mosquito infections are indicated, with corresponding results reported in referenced figure panels. The blue gradient in the background represents the 60-day cumulative rainfall (mm) before each survey, recorded at the Chalinze meteorological station, and the gradient below the graph (yellow to blue) shows the difference in rainfall (mm) compared with the same period 1 year earlier. Screening dates when gametocytaemic blood was collected for the mosquito infection replicates (r1–5) presented in Fig. 5 are indicated. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 3. b, Phylogenetic tree of P. falciparum isolates obtained from 1–2 gametocytaemic children on most screening days. Consensus sequences of the CSP, AMA1, SERA2 and TRAP genes were concatenated and aligned to assess genetic relatedness. Each tip label shows the sample ID, collection date and percentage sequence identity to the P. falciparum NF54 reference genome. Coloured labels correspond to isolates used for mosquito infection experiments and are matched to their respective village of origin as shown in a. The scale bar represents sequence divergence, expressed as the square root of percentage sequence divergence. Raw sequencing data are available under BioProject accession PRJNA1299763 (NCBI SRA).

Children with high gametocyte densities were invited to provide blood samples for mosquito direct membrane feeding assays (DMFAs). Previous studies have shown that infection outcomes from DMFAs correlate closely with those from direct skin feeding, supporting their biological relevance42,43. Of numerous DMFAs conducted, five produced significant oocyst numbers and were processed further. The first three infections were used to assess oocyst counts and sizes at 9 days postfeeding, whereas the last two replicates served to quantify sporozoite loads in mosquito midgut and head and/or thorax tissues using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) at 13–15 days postfeeding. The parasite genotypic analysis confirmed that isolates used for the first three experiments diverge from the NF54 reference genome and from each other (Fig. 4b). Isolates used in the last two infection experiments were not sequenced.

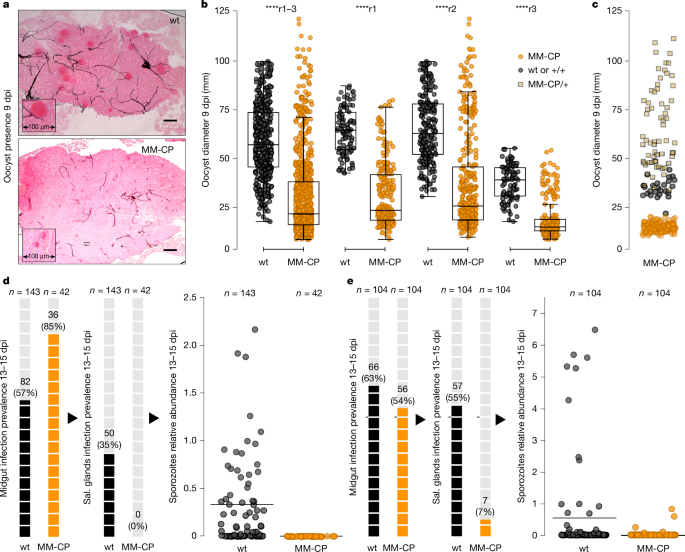

Microscopy showed that most MM-CP mosquito midguts contained notably smaller oocysts (Fig. 5a), consistent with what was previously observed in KIL/G3 MM-CP mosquitoes infected with laboratory P. falciparum38. Quantitative measurements indicated a median oocyst diameter of 22.2 µm in MM-CP compared with 57.3 µm in wt midguts (Fig. 5b). However, some MM-CP mosquitoes also contained larger oocysts, similar in size to those in wt mosquitoes. Molecular genotyping of mosquito carcasses revealed that these midguts derived from heterozygous MM-CP or non-transgenic mosquitoes present in the MM-CP colony (Fig. 5c).

a, Representative images of mercurochrome-stained midguts from wt and MM-CP transgenic mosquito lines at 9 days post-infectious bloodmeal (dpi), showing marked differences in oocyst size. Insets show magnified regions of oocyst clusters. b, Quantification of oocyst diameters in midguts from wt (n = 19, n = 37 and n = 17, respectively) and MM-CP (n = 25, n = 29 and n = 21, respectively) mosquitoes from three independent infections experiments using P. falciparum gametocytes from infected children. The leftmost plot shows pooled data from all replicates (r1–3) and the remaining plots show data from each replicate individually. Boxplots show median, interquartile range and full data range (whiskers) for each group; dots outside the boxplots are outliers. Significance was tested using the Kruskal–Wallis H-test (****P < 0.0001; effect size η2 = 0.355). Note that some variability in oocyst size is also visible in wt midguts, reflecting natural variation commonly observed in wt infections. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 4. c, Oocyst diameters in midguts of the MM-CP line classified by genotype: homozygous MM-CP (orange circles), heterozygous MM-CP/+ (yellow squares) or wt+/+ (grey circles). Note that all oocysts in wt mosquitoes originate from only two midguts, cautioning against any interpretations of size differences relative to heterozygous mosquitoes. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 4. d, Sporozoite data in wt and MM-CP mosquitoes from the fourth infection replicate (r4) assayed at 13–15 dpi. Left, prevalence of midgut sporozoites. Middle, prevalence of sporozoites in head and/or thorax tissues (used as salivary (sal.) glands proxy). Each shaded box represents 5% prevalence. Total numbers assayed and positives are shown. Right, dot plot showing relative sporozoite abundance in head and/or thorax samples. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 5. e, Same analyses as in d, shown for the fifth replicate (r5). Note that between the third and fourth replicates, the colony was further cleaned using pupal case genotyping to enrich for MM-CP homozygotes. Source data are provided in Source Data Sheet 5. Scale bars, 100 µm.

To improve the consistency of phenotypic analyses, we enriched the MM-CP transgene in the colony by implementing a pupal case genotyping strategy to identify and select homozygous individuals, thereby eliminating wt alleles at the CP locus and increasing the proportion of MM-CP homozygotes. In the fourth and fifth replicates, mosquitoes were dissected 13–15 days post-infective bloodmeal, and parasite detection was conducted through qPCR targeting the 18S ribosomal subunit in genomic DNA extracted from midguts and separately from head and/or thorax tissues for those mosquitoes that tested positive for midgut parasites.

Results from the fourth replicate indicated that although 36 (85%) of 42 MM-CP mosquitoes had detectable parasites in their midguts, none (0%) tested positive for parasites in their head and/or thorax, a proxy for salivary gland infection (Fig. 5d). By contrast, 82 (57%) of 143 wt control mosquitoes were midgut positive and 50 (35%) had head and/or thorax parasite presence, showing variable sporozoite loads. Similarly, in the fifth replicate, 56 (54%) of 104 MM-CP mosquitoes tested positive for midgut infection, but only 7 (7%) tested positive for salivary gland infection, all with very low infection levels (Fig. 5e). This contrasts with 104 wt mosquitoes of which 66 (63%) were midgut positive and 57 (55%) showed salivary gland infection.

These findings demonstrate that our earlier observations from a different A. gambiae MM-CP genetic background infected with the laboratory P. falciparum NF54 strain38, characterized by reduced and delayed sporozoite development, impaired oocyst maturation and limited salivary gland invasion, are recapitulated when MM-CP mosquitoes are challenged with genetically diverse P. falciparum isolates from malaria patients. This highlights the robustness of the MM-CP phenotype across parasite genotypes and reinforces its potential for impact under real-world transmission settings. Although we cannot fully exclude the possibility that low-level sporozoite development may eventually lead to transmission, the combination of delayed parasite maturation and reduced post-bloodmeal mosquito survival is projected to severely constrain the likelihood of onwards transmission under field conditions.