In academic output, the gender gap is wider in the physical sciences than in medical fields.Credit: Assembly/Getty

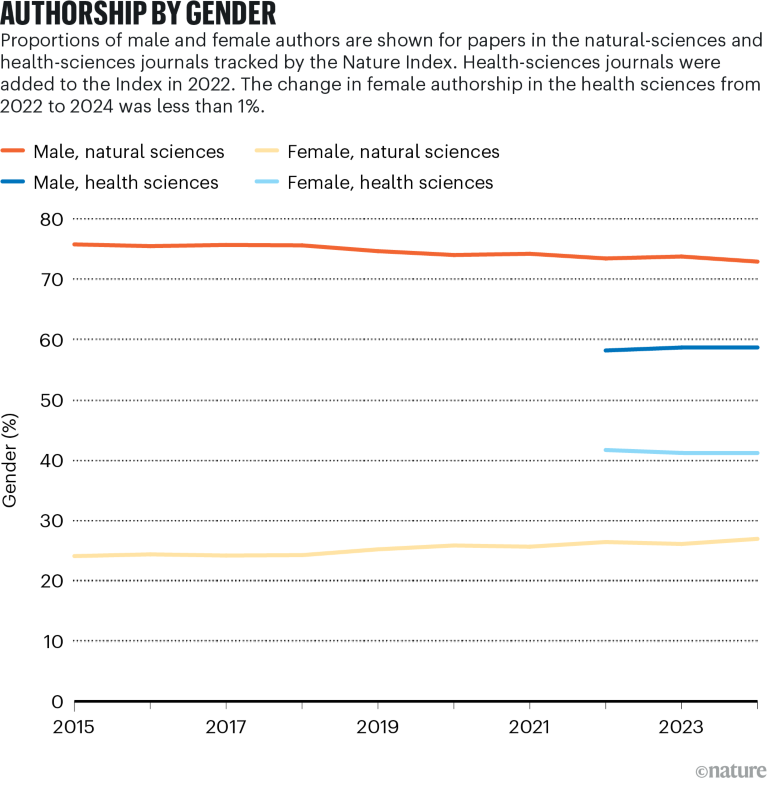

Data from the Nature Index reveal the slow erosion of the gender gap in global research publishing over the past decade. But with just 27% of high-quality papers in the natural sciences having female co-authors in 2024, there is a lot of room for improvement. In the health sciences — where women have a stronger presence — that figure sits at 41% (see ‘Authorship by gender’).

In terms of research topics, the highest representation of female co-authors in 2024 was in reproductive medicine (53%), paediatrics (50%) and nutrition and dietetics (50%). Classical physics (15%), quantum physics (16%) and condensed matter physics (16%) had some of the lowest percentages of female authorship.

Among the leading universities in the Nature Index, as measured by Share (a metric that tracks the contribution of countries or territories and institutions to the natural- and health-sciences journals tracked by the Index), most did not come close to achieving gender parity in research authorship — that is, having women make up 40–60% of authors — in papers overall. In 2024, many of these institutions sat below the 30% mark in terms of female co-authorship. Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts, stands out, however, with 38% female co-authorship.

Of the top ten countries in the Nature Index, only three — the United States, Canada and France (all at 34%) — had a female author representation of more than 30% in 2024.

Results of the analysis are available on the Nature Index website for users to explore.

There are several important caveats to consider when comparing results across countries, institutions and topics, but the clear picture that emerges is how much work is yet to be done to achieve a more balanced gender representation in research publishing.

2024 Research Leaders

“The problem is that men and women do not generally operate under the same conditions,” says Lynn Nygaard, a specialist in academic writing and gender and diversity issues at the Peace Research Institute of Oslo. “There is a skewed distribution between fields, and different fields have different publication patterns and positions, with more men in senior positions and women in junior positions.”

Reaching gender parity will require deep commitment and long-term coordination across countries and institutions, she adds.

Natural sciences still lag behind

One of the clearest trends in the data is how gender balance differs across the natural sciences and health sciences (the latter was added to the Nature Index in 2022). This mirrors what has previously been reported in research sectors worldwide: male researchers tend to dominate in physics, for instance, whereas in the life sciences and health disciplines, the gender gap is not as large.

Of the ten topics with the highest percentage of female co-authors for 2024, most are in the health sciences (see ‘Topic trends’).

The lowest-ranking topics — in which the gender gap is the widest — were mainly chemistry and physical sciences topics, many of which had less than 20% female co-authorship.

On a country level (see ‘Country comparisons’), female authorship is ticking upwards, but progress is very slow. Between 2015 and 2024, the United States increased its female authorship from 26% to 34% — the biggest percentage-point increase among the top ten countries in the Index. South Korea, by comparison, increased its female authorship from 21% to 23% over the same period.

Data limitations

Caution is needed when looking at the results of the country- and territory-level analysis, owing to the limitations of the methodology.

To create the data set, the Nature Index data-analysis team used the chatbot ChatGPT, created by OpenAI, based in San Francisco, California, to infer author genders on the basis of their most likely country of origin and the name–gender association trends in that country (see ‘Methodology’).

Some countries and territories have stronger name–gender associations — in other words, most people with a certain name will identify as a certain gender — than others, which can make the results of the analysis uneven. Authors for whom there is low confidence that the model is accurate in inferring gender have been excluded from the analysis, including the majority of names in some countries, such as China and Singapore.

It’s important, then, to consider the findings of the analysis as an approximation, and to seek other sources when piecing together a picture of gender balance in academic research.

Setting the standard

The institution-level analysis incorporates an extra metric: expected values for the proportion of female authorships at an institution, based on how much research they publish in male- or female-heavy sciences. For example, an institution that predominantly publishes in physics — a field with historically lower female authorship rates1 — will have a relatively small expected proportion of female authors compared with institutions that specialize in health-science research.

If an institution’s actual proportion of female authors surpasses this calculated value, it suggests that the institution is outperforming expectations in promoting gender diversity.

Among the ten leading US universities in the Nature Index, for example, all exceeded expectations for female authorship representation in 2024. The University of Washington, in Seattle, had one of the largest gaps, with an expected proportion of female authorship of 27% versus the actual proportion of 37%. Among the ten leading Japanese universities in the Nature Index, by comparison, none exceeded the expected proportion of female authorship.

Factors behind improvement

There are many reasons for the persistent gender gap in academic publishing, says Nygaard. Her research2 has shown that the gender publishing gap almost disappears once factors such as career breaks for childbirth and childcare, as well as the “more difficult-to-measure challenges that women face”, are accounted for. These include being expected to spend more time providing pastoral care to students and doing academic ‘housework’, such as editing journals and undertaking peer review, and being under pressure to represent women on panels and in media interviews.