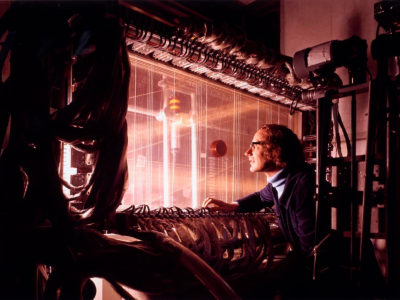

Sharing research findings through non-academic outlets can be rewarding and allow them to reach a wide audience.Credit: Getty

As a marketing academic specializing in children’s consumer behaviour, I’ve always strived for my next journal publication and to earn the respect of my peers. But beneath it all, one question has often nagged at me: who is reading my work?

My research — much of it fusing insights from child development and consumer psychology — was trapped inside academic silos and behind paywalls, out of sight of the educators, parents and policymakers who needed it.

The frustration had nothing to do with failing to get my work published in top journals; while I was building my career as an assistant professor, moving from the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign to the University of Arizona in Tucson, and again to Villanova University in Pennsylvania, I published papers in all of the right places. But I felt as if I was failing to keep pace with the real-life questions that educators and families have every day about the impact of marketing on children’s well-being.

Before making a career move, try an experiment

The long delays between submitting a manuscript and eventually seeing it in print had also taken much of the joy out of research for me. In one of my projects, for example, I examined the happiness that children derive from experiences, such as going to see a film or playing sports, compared with the happiness that they derive from owning material goods — and how these tendencies change with age. That paper went through two different journals and three editorial teams before it saw the light of day, eight years after it was initially submitted.

I started my career in 2003, before digital publishing became standard practice. My early journal articles often took months to appear in print after acceptance. Because marketing as a field is fast-paced — and because children are especially vulnerable to evolving marketing messages — I recognized a need to share my research findings more promptly, effectively and broadly than journal publications alone allowed.

From around 2007, I took four steps to ensure that my research reached a wider audience quickly and had a meaningful impact.

Reflecting on my role as an academic

The first step was perhaps the most difficult: I started going to therapy to come to terms with my growing frustration and burnout from following the conventional academic path.

I struggled with not feeling happy despite having made a strong start to my academic career, and feeling empty even though I had earned the respect and support of my peers. I constantly questioned my purpose as a researcher.

Tips and tricks to plan your career in science

Therapy helped me to acknowledge that I was putting too much pressure on myself to stick to the conventional publishing grind.

My therapist proposed that I write a reflective letter from the perspective of my future self, praising what I had already achieved, as well as suggesting theoretical actions that I could take to help accomplish my goals. This allowed me to better appreciate the specific actions that I had already taken to build a career that truly made me happy. As I wrote the letter, I detailed the ways that I had constructed a career defined by my own ambitions and interests, rather than by others’ expectations and ideals.

In the letter, I encouraged myself to take risks, to let go of outdated graduate-school definitions of success and to continuously seek out opportunities that inspired and energized me. Ultimately, this gave me the ability to imagine a different, more-rewarding way forwards.

Armed with this fresh perspective, I took the next step towards sharing my work broadly. In 2009, about four years after I had published my first research paper in the Journal of Consumer Research, I became more intentional about publishing in journals that aren’t focused solely on consumer marketing research.

Searching for other outlets

I began submitting papers to journals that publish articles on topics outside my core academic focus, ones that attract a wider readership of people interested in research on children’s happiness and their choices, such as the Journal of Happiness Studies1, Child Development2 and Psychological Science3. I also worked with my university’s media-relations team to write both non-technical summaries and press releases whenever I published work, and actively sought expertise on communicating with journalists. Despite being nervous about talking to the media, I made it a priority to respond to every interview or information request that I received and, in doing so, managed to reach a non-academic audience.

Small, affordable undergraduate research programmes changed my career and strengthen US science. Why cut them?