Food prices are increasing almost everywhere. Disruptions and declines in food production owing to climate extremes are part of the reason1,2. But our analysis of global spending on the innovations that underpin food production and the processes that get it to people’s tables shows major shifts in investment in agricultural science. These could help to explain why demand for food is getting out of balance with supply — and why things are likely to get worse.

How farming could become the ultimate climate-change tool

From 1980 to 2021, the world’s population increased by almost 80% (by 3.5 billion people). Owing to agricultural science, food and other farm products have become more plentiful over this period for most people on the planet — by no means all.

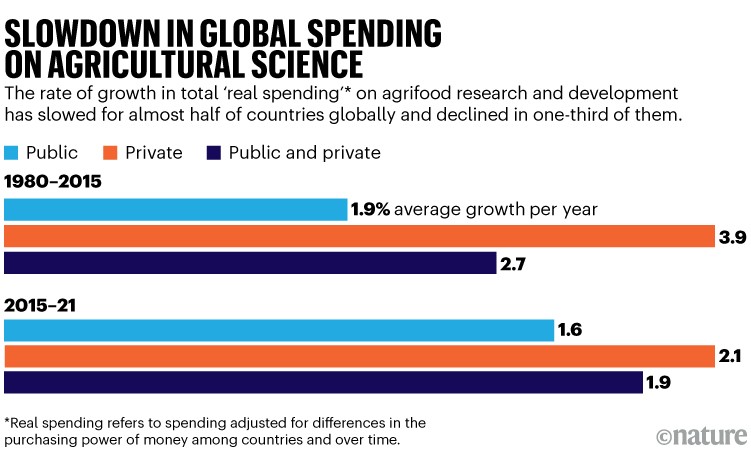

Our analysis of public and private spending on research and development in agriculture and food (agrifood R&D) for 150 countries from 1980 until 2021 shows an alarming trend, however. Between 2015 and 2021, the annual average rate of growth in total ‘real spending’ on agrifood R&D over 6 years was one-third less than it was during the 35 years between 1980 and 2015. (Real spending refers to spending adjusted for differences in the purchasing power of money among countries and over time; see also Supplementary information.) When comparing these two time periods, growth in absolute spending has slowed for more than half of the world’s countries. In one-third of them, spending has even declined. This has happened even though demand for food and other agricultural products continues to increase, thanks to growing populations and rising incomes3.

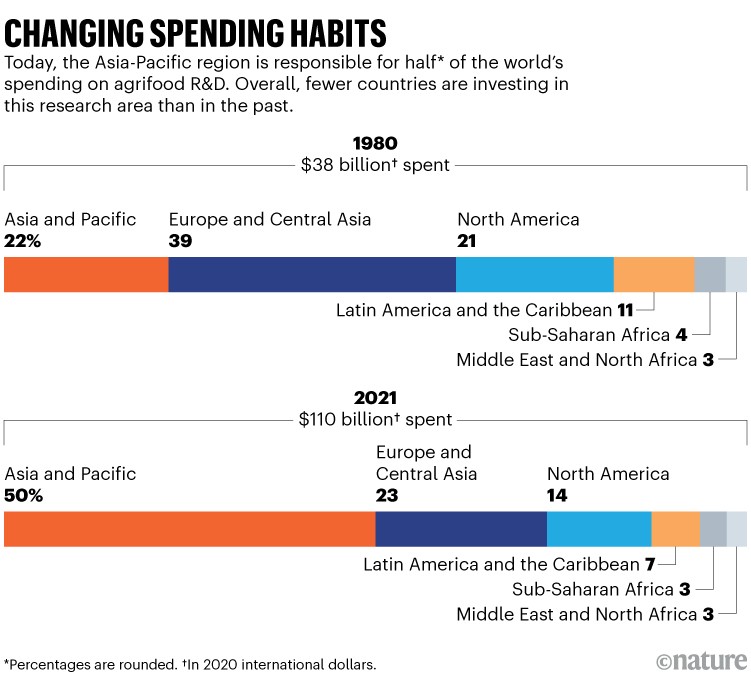

The countries and sectors that are investing most in agrifood R&D are changing, too. In 1980, the public sector, including government agencies and universities, was responsible for two-thirds of the world’s spending on this research area. By 2021, private-sector spending had caught up with that from the public sector. And whereas high-income countries were the top spenders in 1980, by 2021, middle-income countries had overtaken high-income ones. Today, the Asia-Pacific region is responsible for half of the world’s spending on agrifood R&D (see ‘Changing spending habits’).

Source: Analysis by P. G. Pardey et al.

Early signs of these shifts were evident in 2016 when we conducted a similar analysis of R&D spending from 1980 to 2011 in 130 countries4. Still, we were surprised by the extent and speed of the changes since then — particularly the widespread slowdown in spending.

It generally takes years or decades until spending on agrifood R&D widely benefits farmers and consumers. So a slowdown in the growth of R&D funding, or an overall decline, will eventually mean higher food prices for decades to come and increased pressures on the natural resources that underpin food production. Likewise, the shifting balance in spending by the public and private sector and by high- and middle-income countries will affect what kind of research gets done, and which producers and consumers around the world benefit from the resulting innovations.

Some of these trends must be reversed — fast — if the world’s farmers are to have any chance of sustainably meeting the expected growth in demand for food, animal feed, textile fibres and agriculturally sourced fuel by 2050 (the relevant timeline given the R&D lags that are at play5).

Three seismic shifts

Although the growth has come with important environmental and societal downsides as well as upsides, the real value of agricultural output increased by 137% — from $1.69 trillion to $4.15 trillion (in international dollars)6 between 1980 and 2021.

The rise in agricultural output over the past 40 years comes mainly from improved production systems, such as those for cotton in China (left) and milk in Austria.Credit: Tao Weiming/VCG via Getty; Simone Padovani/Getty

Around 96% of this increase in production has come from increasing the amounts of crops, meat, milk and other agricultural outputs produced per unit of land. (The other 4% is from expanding how much land is used.) And these productivity gains are mostly the result of increasing the amounts of fertilizers, seeds, machinery and other inputs used per unit of land; improving the quality of such inputs; and increasing the size and specialization of farms. All of those changes have been enabled by public and private investment in agrifood R&D7.

Three shifts in the global investment in agricultural science are changing the picture, however.

Spending slowdown

Our analysis of statistical reports, studies of R&D investments, company annual reports, government-agency databases and other sources show that between 2015 and 2021, the growth in real public and private sector spending on agrifood R&D combined was around 1.9% per year. From 1980 to 2015, it was 2.7% per year.

Comparing these two time periods, for the 38 high-income countries in our analysis (as a group), the growth rate in R&D spending has fallen from 2% to around 1% per year (see ‘Slowdown in global spending on agricultural science’). As with the worldwide pattern, rates of growth in spending have slowed in nearly half of these countries, and almost one-quarter of them have reduced their public spending on agrifood R&D.

Source: Analysis by P. G. Pardey et al.

In the 67 middle-income countries, the rate of growth in spending was 3.8% per year in 1980–2015. In 2015–21, it was just 2.7% per year. Of these countries, 39 (58%) have slowed their rates of growth in spending and 19 (28%) have reduced their spending. Meanwhile, for the 21 low-income countries in our analysis, growth in spending on agrifood R&D dropped from 2.3% per year before 2015 to 1.7% per year afterwards. More than half (57%) of these countries have reduced their real spending since 2015.

Rise of middle-income countries

In 2021, middle-income countries produced about 73% of the world’s agricultural output (up from around 56% in 1980), with China, India and Brazil accounting for 41% of the 2021 total6. Today, these three nations are among the top five agrifood R&D spenders. The United States now lags well behind China on this metric8. For public-sector research, the United States is behind India, too.

Also, fewer countries are now responsible for a larger share of the total (public and private) spend on agrifood R&D. And the difference in spending between low-income countries and the rest of the world is increasing. In 2021, the top ten countries in R&D spending accounted for 69% of the global total — up from 66% in 1980. Meanwhile, the share of spending for the bottom 50 countries fell from around 1% in 1980 to 0.5% in 2021.

Rise of the private sector

The global slowdown in public agrifood R&D spending growth has coincided with a larger contribution from the private sector, including many small and all the large agrifood corporations. In 2021, private firms accounted for nearly 50% of the global spend on agrifood R&D, up from around 32% in 1980. And this trend is not confined to high-income countries. Private R&D spending now makes up 54% of the total R&D spend in upper-middle-income countries — up from 15% in 1980.

All of these changes are happening because of multiple political and socio-economic influences.

A revolution is sweeping Europe’s farms: can it save agriculture?

Spending on agrifood R&D has increased in upper-middle-income countries probably because food insecurity is a high policy priority for these economies, with their vast populations and relatively recent experiences of widespread hunger. Conversely, complacency and shifting priorities are probably what’s causing spending in many high-income nations, particularly by the public sector, to stagnate or shrink.

This complacency seems to be setting in even though, on average, each dollar invested in agrifood R&D yields a total social return of $10 (in present value terms and counting benefits to both producers and consumers), and often much more9,10. But agricultural R&D is slow to take effect and most people and their political representatives are impatient. Certainly, in the United States, agrifood R&D tends to receive less political support compared with farm subsidy or other programmes that have more immediate impacts on farmers and consumers11.

As economies develop, farms become more reliant on technology and less reliant on labour. Also, people’s diets change as their incomes increase, with processed food or restaurant food often being favoured over meals prepared at home. These changes incentivize private-sector investment in R&D across the entire food-supply chain, but especially for innovations related to transporting, processing or retailing food and new food products. In 2021, R&D related to food processing, storage and logistics made up 58% of all agrifood R&D in high- and upper-middle-income countries. In fact, in the United States today, 90 cents of every dollar spent on food pays for these post-farm activities6.

Trouble ahead

So what do these trends mean for the future?

It generally takes decades for the benefits from investments in agrifood R&D to be fully realized5. After the 6–10 years it takes to breed new varieties of wheat or soya beans, for instance, several more years are needed to produce enough seed to sell them commercially. It can then take years or decades for the new varieties to be adopted at scale across farmers’ fields for a host of reasons. These include a lack of economic incentives or transportation infrastructure, and underdeveloped links between farms, suppliers of inputs (seeds and fertilizer) and downstream food transporters, processors and traders.

Also, because of biological and physical constraints, such as limits to how efficiently plants can convert sunlight, water and other crop inputs into biomass, humanity has generally managed to increase crop and livestock yields only linearly, not exponentially. This means that any absolute increase in crop or animal yields (such as milk or meat production per animal) as a proportion of current yield or current production shrinks over time.

For example, our analysis shows that in 1961, it took just 12 years to increase global average wheat yields by 50%. Looking back from 2022, increasing global average wheat yields by 50% took 31 years. For rice yields, it took 40 years (compared with 20 in the 1960s). For soya bean yields, it took 34 years (compared with 16 in the 1960s; see go.nature.com/3m7fp2t). And today, owing to climate change and depleted natural resources, it is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain yields, let alone achieve even a constant absolute annual increase in agricultural productivity.

Workers check harvested carrots on a sorting line in Laixi, China.Credit: Zhang JinGang/Feature China/Future Publishing via Getty

Countries need to be increasing their rates of annual investment in agrifood R&D just to sustain the current rates of growth in farm productivity. It will take decades for the harmful consequences of current R&D spending slowdowns to be realized, including increased environmental damage, poverty, malnutrition and civil or military strife. And it will take many more years to undo the damage from the recent slowdowns in R&D spending.

A slowdown in agrifood innovation —whether it entails developing better ways of managing water, soil health or pests, developing crop varieties, animal breeds or better systems for storing, processing and transporting food — is already driving up food prices. Further cutbacks in science and technology that result from governments ramping up their spending in other areas, such as defence, or looking to trim their overall budgets following heightened spending during the COVID-19 pandemic, will eventually result in a resurgence of hunger and malnutrition and further undermine the health of the environment.

The increased contribution by the private sector to total global spending on agricultural science is encouraging. But private companies cannot fill the gap in public spending. Corporations tend to focus on the patentable farming and food-manufacturing technologies that they can sell to farmers and those engaged in supply-chain activities and processes. Such technologies, developed on the back of fundamental discoveries made through publicly funded research, are more directly linked to the commercialization of farm products. Consequently, cutting publicly funded R&D slows overall progress and reduces the effectiveness of private innovation.

The shifts in where agrifood R&D is being done are concerning, too, because technologies developed in one country are not necessarily deployed in another as effectively or easily. Also, it is unclear whether past patterns of technology transfer between countries will be sustained going forward.

Indigenous knowledge is key to sustainable food systems