The response of magnetization to external stimuli has drawn attention for more than a century, providing fundamental insights into the physical mechanisms behind magnetization dynamics. The Stoner–Wohlfarth model, proposed in 1948, describes the magnetization reversal in the form of coherent rotation of a single-domain ferromagnetic nanoparticle1 (Fig. 1a). Beyond its fundamental importance as a type of hydrogen model for ferromagnetism2, it provides guidance for the design of magnetic devices for data computing and information storage8,9. However, the simplicity of the model makes it arduous for explaining the magnetic behaviour of other ferromagnetic systems, which usually have multidomain structures associated with unavoidable defects. In this regard, vdW magnets exhibit a natural advantage, as their defect-free vdW interfaces allow them to be considered single-domain, at least in the vertical dimension. Such 2D FMs with strong interlayer coupling can be called the Stoner–Wohlfarth FMs, such as Fe3GeTe2, whose magnetic reversal behaviours are well described by the Stoner–Wohlfarth model below a certain thickness10.

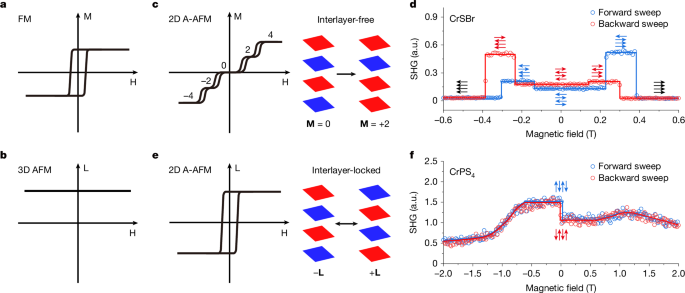

a, Binary switching of magnetization controlled by the magnetic field in FMs. b, Magnetic-field-insensitive Néel vector in conventional 3D AFMs. c, Interlayer-free 2D A-type AFMs (2D A-AFMs). Left, the evolution of magnetization with the magnetic field (taking 4L as an example). The corresponding magnetization is marked on each plateau. Right, schematic of interlayer-free flipping from M = 0 to M = +2. The red or blue quadrilaterals represent a ferromagnetic layer with opposite magnetization, +1 or −1, respectively. d, SHG hysteresis loop on 4L CrSBr with the in-plane magnetic field between ±0.6 T sweeping along the easy axis of CrSBr. The assignment of magnetic states during transitions is discussed in ref. 12. e, Interlayer-locked 2D A-AFMs. Left, FM-like binary switching of Néel vector controlled by the magnetic field. Right, schematic of interlayer-locked flipping between +L and −L. f, SHG hysteresis loop on 4L CrPS4 with the out-of-plane magnetic field between ±2 T. a.u., arbitrary units.

As an extension, is there a Stoner–Wohlfarth AFM—a single-domain AFM whose antiferromagnetic order (Néel vector L) can be coherently switched 180° by the magnetic field? From an application perspective, seeking such AFMs is crucial for improving the data-storage density and information-processing efficiency attributed to their zero stray field and ultrafast dynamics3,4. For the conventional three-dimensional (3D) collinear AFM, however, a 180° switching of the Néel vector is unavailable owing to the vanishing Zeeman energy (Fig. 1b). Although recently a new type of collinear AFM known as altermagnets has been demonstrated to exhibit 180° switching of the Néel vector, they are not the Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs, as the incomplete switching ratio revealed by the anomalous Hall effect suggests the existence of microscopic multidomain structures5,6,7. Of particular interest are the 2D vdW A-type AFMs, in which spins within each layer order ferromagnetically and adjacent layers couple antiferromagnetically. The weak interlayer magnetic coupling leads to their controllable antiferromagnetism. The magnetic evolution of some representative 2D A-type AFMs, such as CrSBr (refs. 11,12) and CrI3 (refs. 13,14), has been extensively studied in the past, following a behaviour of layer-by-layer flipping with the magnetic field, as sketched in Fig. 1c and illustrated in Fig. 1d for 4L CrSBr and Extended Data Fig. 1 for 4L CrI3. Such AFMs are also not the expected Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs because the Néel vector is not coherently switched to its antiphase state at once (L to −L) but tends to a metastable state by an interlayer-free flipping (Fig. 1c).

Here we report a new type of 2D vdW A-type AFM, CrPS4 as a representative, whose antiferromagnetic order undergoes an interlayer-locked antiferromagnetic switching (Fig. 1e). The magnetic evolution manifests as a FM-like binary switching (Fig. 1f) rather than the layer-by-layer flipping observed in interlayer-free AFMs. CrPS4 is an air-stable vdW semiconductor and crystallizes into a non-centrosymmetric monoclinic structure with space group C2 (refs. 15,16). As shown in Fig. 2a, the material forms an A-type antiferromagnetic order along the c-axis below the Néel temperature 38 K (refs. 16,17,18). Transport measurements in CrPS4 indicate that its magnetic behaviour undergoes a spin-flop transition into a canted state at approximately 0.7 T, followed by a spin-flip transition into a ferromagnetic state around 7 T under an out-of-plane magnetic field19,20,21 (schematically shown in Extended Data Fig. 2). Besides, recent reflective magnetic circular dichroism (RMCD) studies show a clear hysteresis loop below the spin-flop field in odd-layer CrPS4, suggesting the existence of further magnetic transitions16. However, RMCD is only sensitive to the net magnetization, so it fails to uncover the layer-resolved magnetization reversal for this transition and, more importantly, it is incompetent to investigate the magnetic evolution of even-layer CrPS4 whose net magnetization is zero.

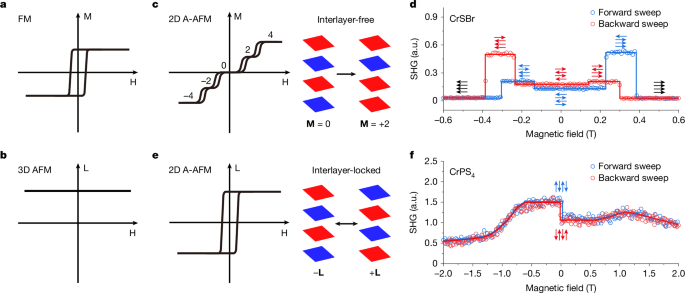

a, Crystallographic and magnetic structure of CrPS4. The magnetic moments denoted by the red and blue arrows on Cr3+ alternate oppositely between adjacent layers. b, Optical microscopic image of a CrPS4 flake (sample 1) with the labelled layer thicknesses. Scale bar, 5 μm. c–h, SHG and RMCD hysteresis loops on 2L (c,f), 3L (d,g) and 4L (e,h) CrPS4 with the out-of-plane field between ±0.1 T. i, Symmetry transformation of the non-centrosymmetric antiferromagnetic state in even-layer CrPS4 under the spatial-inversion operation i. The spatial-inversion operation converts one antiferromagnetic state to the other but not to itself. j, Symmetry transformation of the centrosymmetric antiferromagnetic state in odd-layer CrPS4. a.u., arbitrary units.

To reveal the barely detectable antiferromagnetic order and its potential evolution, we use the second-harmonic generation (SHG) microscopic technique because the nonlinear optical signal is no longer restricted by the net magnetization but is sensitive to the symmetry changes12,14,22,23. The SHG process typically originates from the dominant electric-dipole mechanism and the prerequisite for this process is the broken spatial-inversion symmetry. The layered antiferromagnetic order such as even-layer CrPS4 simultaneously breaks both the spatial-inversion and time-reversal symmetries, thus contributing time-noninvariant (c-type) electric-dipole SHG and permitting SHG to detect the antiferromagnetic order and symmetry-related phenomena.

Figure 1f shows a typical magnetic-field-dependent SHG loop on tetralayer CrPS4 at 6.5 K, in which the field is perpendicular to the sample and sweeps forward and backward between ±2 T. At high magnetic fields beyond ±0.7 T, the loop exhibits a smooth trajectory, originating from the gradual canted states associated with spin-flop transition (Extended Data Fig. 2). Notably, a clear FM-like hysteresis loop appears at much lower fields (±0.01 T), indicating the existence of further magnetic transitions in CrPS4.

We further focus on this FM-like loop and examine its layer-dependent evolution. Figure 2b shows the optical microscopic image of few-layer CrPS4 with thicknesses of 2L–4L. As well as the tetralayer, this FM-like switching also exists in the bilayer but is absent in the trilayer (Fig. 2c–e). Without loss of generality, similar odd–even-layer contrast is shown for other thicknesses in Extended Data Fig. 3. Notably, when the polar RMCD is used for the same sample, the features are exactly opposite to that of SHG. Only the odd layers show the hysteresis loop, whereas all of the even layers do not (Fig. 2f–h). As the temperature increases, the hysteresis loops observed in both SHG and RMCD shrink and eventually vanish at the critical temperature of around 34 K, at which the antiferromagnetic order disappears (Supplementary Text 1 and Extended Data Fig. 4).

For even-layer CrPS4, the single FM-like loop present in SHG but absent in RMCD suggests that the magnetic transition near 0 T originates from the antiferromagnetic binary switching. That means, when applying a magnetic field along the out-of-plane direction of CrPS4, all layers are antiferromagnetically locked and simultaneously flipped to their time-reversal counterpart, that is, switching from the +L state to the −L state. Because the layered antiferromagnetic order of even-layer CrPS4 breaks the spatial-inversion symmetry (Fig. 2i), c-type SHG χ(c) emerges and couples linearly to the Néel vector, which is expressed by χ(c)(−L) = −χ(c)(L). Besides, the crystallographic structure of CrPS4 is non-centrosymmetric, resulting in the extra time-invariant (i-type) SHG χ(i). Therefore, when the switching between the time-reversal antiferromagnetic counterparts occurs, the self-interference |χ(i) ± χ(c)|2 leads to the intensity contrast in SHG loops24,25,26. The antiferromagnetic switching is further supported by the helicity-reversed SHG loops (Extended Data Fig. 5), in which the helicity of excitation is equivalent to exerting a time-reversal operation to the system (see details in Supplementary Text 2). However, the switching is invisible in RMCD signals as the magnetization of even layers is completely compensated.

For odd-layer CrPS4, owing to the uncompensated magnetization, a hysteresis loop emerges in RMCD signals, verifying that the antiferromagnetic switching also exists in odd-layer samples. To understand the absence of SHG loop in odd layers, we noted that the layered antiferromagnetic order alone for odd layers is centrosymmetric, as illustrated in Fig. 2j. Yet, because of the broken spatial-inversion symmetry in crystallographic lattice, both χ(i) and χ(c) can be non-zero. The centrosymmetric antiferromagnetic order substantially alleviates the degree of symmetry breaking—leading to negligible χ(c). As a result, the SHG signals of odd-layer samples remain constant during the antiferromagnetic switching.

Very recently, a study by Ho et al.26 also provided evidence for the antiferromagnetic switching in few-layer CrPS4 using the SHG technique. By applying opposite saturating magnetic fields (±9 T) and then returning to 0 T, they observed weak distortions in polarization-resolved SHG patterns, consistent with antiferromagnetic switching. As discussed below, interlayer-free AFMs can also exhibit magnetic-field-driven switching but through a fundamentally different mechanism. However, the work by Ho et al.26 did not track the switching hysteretically with magnetic fields, leaving this key mechanistic distinction unresolved.

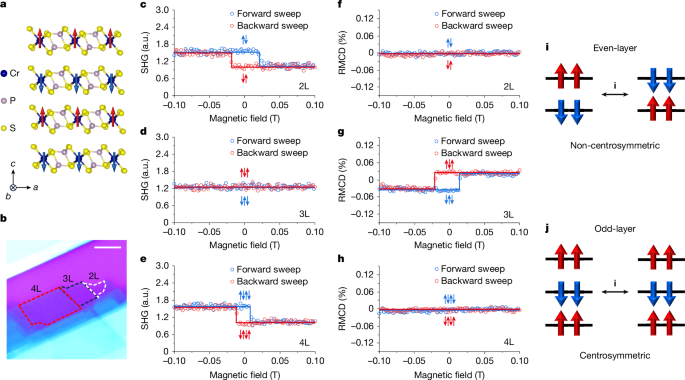

To explain the distinct antiferromagnetic switching between the interlayer-locked and interlayer-free AFMs, magnetic-field-dependent SHG was also performed on an interlayer-free AFM CrSBr. CrSBr is an A-type AFM with in-plane antiferromagnetism along its easy b-axis direction11,23,27. Because SHG signals from two antiferromagnetic ground states nearly degenerate in intensity but reverse in phase, we use the interference between the SHG fields from the antiphase states and that from an external reference to distinguish them effectively12 (see Methods and Supplementary Text 3 for details). Figure 3 shows the phase-resolved SHG hysteresis loops with an in-plane field along the easy axis under different sweeping ranges on the tetralayer CrSBr. The stepwise jump between adjacent signal plateaus is caused by the magnetization flipping of an individual layer. When an antiferromagnetic state from a unidirectional sweep is driven to a ferromagnetic state at ±0.6 T and then returns to 0 T (major loop in Fig. 3a), the non-overlapping signal plateau indicates that it can be switched to the other antiferromagnetic counterpart. By contrast, if the antiferromagnetic ground state is only driven to ±0.35 T, the switching to the other antiferromagnetic counterpart would not occur (minor loops in Fig. 3b,c). Thus, for the interlayer-free AFM, the antiphase states can only be obtained by a complete multistep layer-by-layer sequence, rather than by reversible binary switching as observed in the interlayer-locked AFM CrPS4.

a, Major phase-resolved SHG (denoted ‘Phase-SHG’) loop on 4L CrSBr, in which the in-plane field is swept from −0.6 T to +0.6 T and then back to −0.6 T along the easy axis of CrSBr. The antiferromagnetic state at 0 T is switchable but requires undergoing a complete layer-by-layer switching. b,c, Minor phase-resolved SHG loops on 4L CrSBr, in which the in-plane field is swept from −0.6 T to +0.35 T and then back to −0.6 T in b and from +0.6 T to −0.35 T and then back to +0.6 T in c. The antiferromagnetic state is not switched when the magnetic field reverses in an intermediate state before the ferromagnetic state. a.u., arbitrary units.

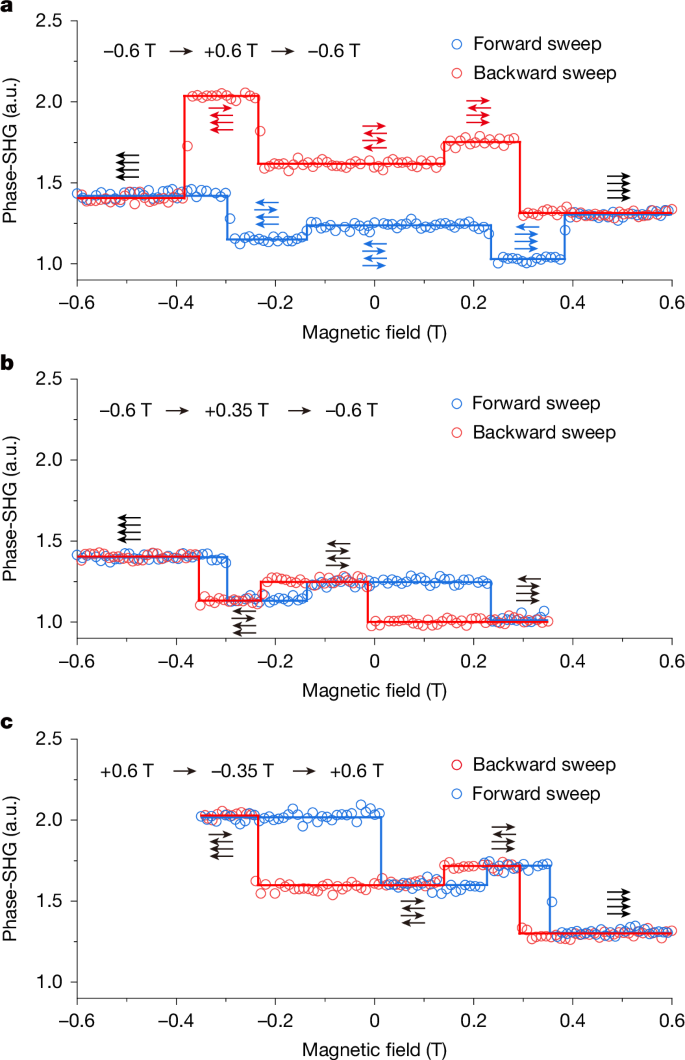

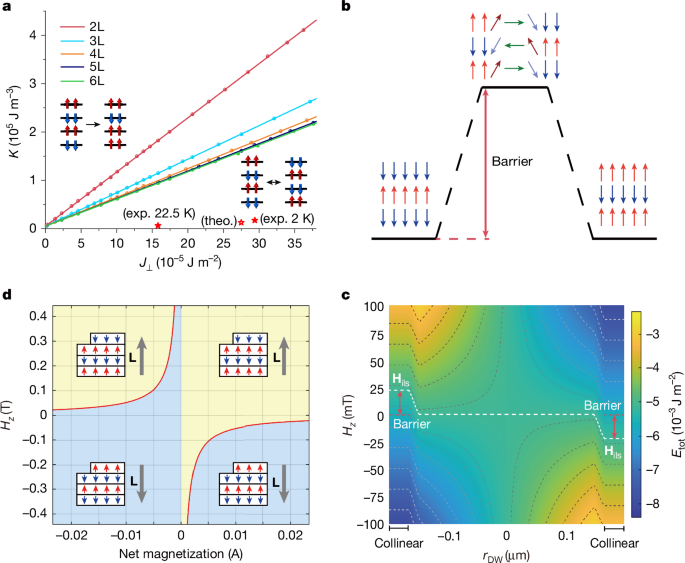

To gain a better understanding of the switching behaviour, we apply the micromagnetic module in COMSOL Multiphysics28,29 to simulate magnetic switching of few-layer CrPS4. Starting from the A-type antiferromagnetic order with out-of-plane intralayer magnetizations, we artificially reverse the bottom-layer magnetization and track the evolution of the others. Figure 4a shows the resulting phase diagram as a function of the interlayer exchange J⟂ and the effective anisotropy K (see Methods for details). Both the interlayer-free and interlayer-locked behaviours are obtained, with their boundaries shown by the circles for each thickness. When J⟂ is sufficiently strong, adjacent layers overcome the anisotropy barrier and all layers ultimately reverse, producing the interlayer-locked behaviour; otherwise, only the bottom layer switches, yielding the interlayer-free behaviour. In the few-layer limit, the phase boundary between them depends on the layer thickness. When the layer number reaches four or more, the phase boundary tends to converge. Experimental30,31 and computational16 estimates of J⟂ and K for CrPS4 fall well below this boundary, consistent with the interlayer-locked switching.

a, Simulated phase diagram of magnetization switching in 2D A-type AFMs. The dots are the simulated boundaries between interlayer-free and interlayer-locked switching and the solid lines illustrate the linear fitting. The stars indicate the experimental and calculated magnetic parameters of CrPS4, all of which lie below the phase boundary. b, Energy-barrier profile of magnetic switching for 3L CrPS4. The high-energy plateau corresponds to an intermediate state containing a non-collinear domain wall between two collinear antiferromagnetic configurations with a lower energy. c, Calculated energy landscape of 3L CrPS4 as a function of domain-wall position rDW and external field Hz. The dashed white line represents the iso-energy contour of the high-energy plateau with a domain wall in b. The coercive field Hils for interlayer-locked switching provides a Zeeman energy to overcome the energy barrier between high-energy and low-energy plateaus. d, Calculated coercive fields (indicated by red lines) for switching the Néel orders (grey arrows) of 4L CrPS4, with the adjacent 3L contributing to the net magnetization. Yellow/blue regions denote +z/−z Néel orders, respectively.

Both experiment and simulation indicate that few-layer CrPS4 is a representative Stoner–Wohlfarth AFM. To describe the FM-like binary switching in AFMs, we extend the Stoner–Wohlfarth model originally for the FMs1 by explicitly including the interlayer antiferromagnetic exchange energy (see Methods). This extended Stoner–Wohlfarth model yields a characteristic exchange length, \(l_\rmex=\sqrtJ_\perp d/(2K)\), with d being the interlayer distance, for determining the coherent Néel-vector switching. For a quantitative comparison, we estimate lex of the reported A-type AFMs, including CrI3, CrSBr, CrPS4 and MnBi2Te4, as listed in Extended Data Table 1. For CrPS4 and MnBi2Te4, lex exceeds the interlayer distance, so switching one layer must influence its neighbours. Indeed, the RMCD loops measured on few-layer MnBi2Te4 show the similar interlayer-locked switching behaviour (Extended Data Fig. 6). For the sample thickness larger than lex, the switching can still coherently extend to the entire stack unless interrupted by disorder, such as stacking fault. Experimentally, interlayer-locked switching is seen in CrPS4 up to 8L using SHG, whereas thicker flakes with opposite Néel vectors cannot be distinguished by SHG (Extended Data Fig. 7). By contrast, for CrI3 and CrSBr, the exchange lengths are shorter than the interlayer distance, resulting in their interlayer-free switching, which excludes them from the Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs.

Examining the hysteresis loops shown in Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 3, the coercive fields of the few-layer CrPS4 are mostly symmetric with respect to the positive and negative magnetic fields and only a few exhibit some noticeable lateral exchange bias effect that was recently observed in micron-sized samples by using scanning nitrogen-vacancy centre magnetometry32,33,34. Moreover, the coercive fields between odd-layer and even-layer CrPS4 have comparable magnitude, on the order of 10–100 mT. The small difference suggests that the magnetization-switching dynamics in the lateral dimension occurs through the domain-wall propagation rather than uniform coherent rotation, as the former is energetically more favourable than the latter.

For odd-layer samples, the ground states are collinear antiferromagnetic with non-zero net magnetization pointing up or down, shown as the low-energy plateaus in Fig. 4b. Switching between them occurs by means of a propagating domain wall and the strong interlayer exchange of Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs consistently ensures coherent rotational coupling along the vertical dimension. The introduction of a domain wall increases the energy of the system owing to its non-collinear magnetic components, resulting in an energy barrier. When one ground state acquires sufficient Zeeman energy under the magnetic field, it can overcome the barrier, with the coercive field Hils = ΔE/Mnet, in which Mnet is the net magnetization and ΔE denotes the energy barrier determined only by the intralayer exchange. Figure 4c shows the calculated energy landscape of a trilayer CrPS4 as a function of domain-wall position rDW and external magnetic field Hz. The predicted switching field matches the experimental results in Fig. 2.

For even-layer samples with fully compensated magnetization, the absence of total Zeeman energy makes the switching much more challenging than in the odd-layer counterparts. Nevertheless, our samples are non-isolated. The laterally connected odd-layer regions can first undergo interlayer-locked switching under a magnetic field. The layer-sharing effect12, originating from the strong intralayer exchange, enables subsequent antiferromagnetic switching in even layers by means of the domain-wall propagation (see animation in Supplementary Video 1). Taking a laterally connected trilayer and tetralayer as an example, we calculated the coercive field needed to switch the tetralayer Néel order, with the adjacent trilayer providing net magnetization. As shown in Fig. 4d, the even-layer coercive field is comparable with that of the adjacent odd layer and scales inversely with the uncompensated magnetization. Consistently, the measured coercive fields vary with sample configurations (Extended Data Fig. 8) and modifying the local environment of an even-layer flake by means of the in situ femtosecond laser microcutting technique12 greatly alters its coercive field (see details in Supplementary Text 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

It is necessary to clarify that such domain-wall-mediated magnetization reversal is universally present in vdW A-type AFMs, as well as being observed in the interlayer-free AFMs, such as CrSBr (ref. 12). As illustrated in Supplementary Video 1, however, the weak interlayer exchange interaction can only sustain domino-like behaviour within a monolayer. Such magnetization dynamics, restrained by the vertical exchange length, also distinguishes the interlayer-free AFMs from the Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs.

In summary, we have demonstrated few-layer CrPS4 as a representative of the Stoner–Wohlfarth AFM and revealed its interlayer-locked antiferromagnetic switching behaviour, which is distinct from the layer-by-layer flipping observed in the interlayer-free AFMs. Such Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs shall be ubiquitous in A-type layered antiferromagnetic materials, for example, MnBi2Te4. Moreover, the properties of Stoner–Wohlfarth AFMs, such as switching field and remnant magnetization, may be manipulated by breaking the interlayer symmetry using a displacement field and electrostatic doping, as demonstrated in recent work on bilayer CrPS4 (ref. 21). Furthermore, the interconversion between the two types of layered AFM could be controlled by effectively tuning the ratio between interlayer exchange and magnetic anisotropy, for example, through adjustable nonmagnetic interlayer spacers35 and manipulative interlayer stacking36,37,38 or strain39. Our study therefore consolidates the fundamental understanding of magnetic switching in layered AFMs and exhibits great potential for integrating 2D antiferromagnetic materials as active components into future spintronic applications.