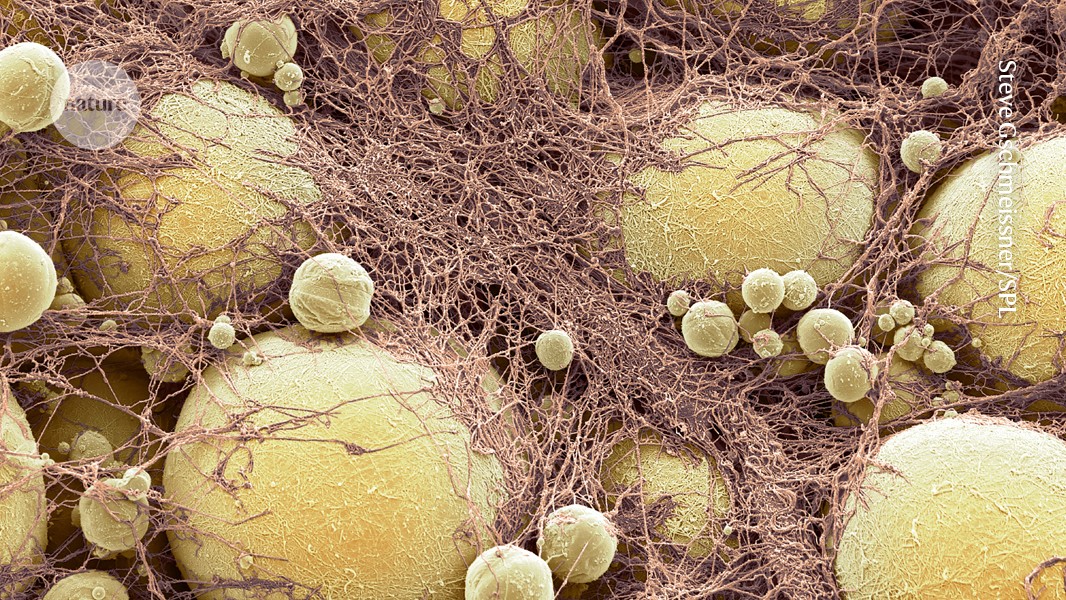

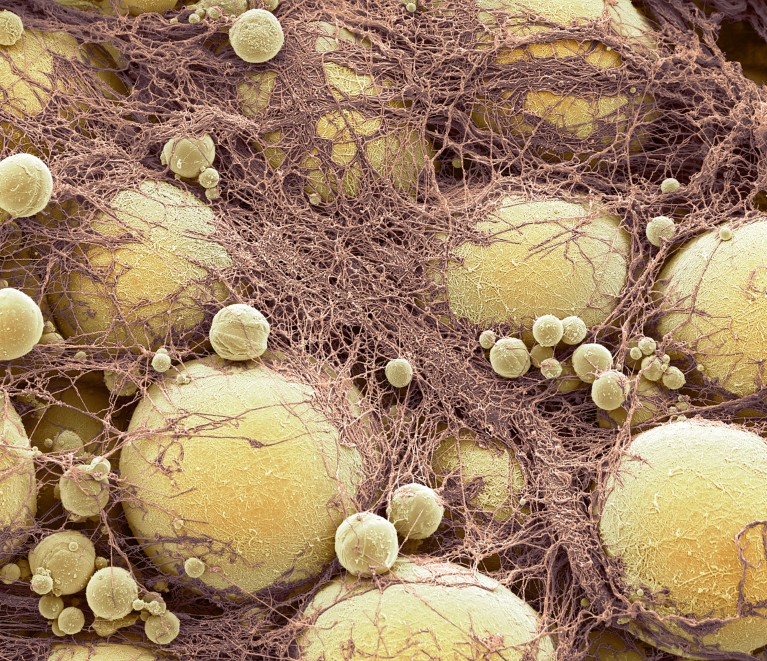

Human fat cells (shown here in a coloured scanning electron microscopy image) carry a ‘memory’ of obesity, a study has shown.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/SPL

Even after drastic weight loss, the body’s fat cells carry the ‘memory’ of obesity, research1 shows — a finding that might help to explain why it can be hard to stay trim after a weight-loss programme.

This memory arises because the experience of obesity leads to changes in the epigenome — a set of chemical tags that can be added to or removed from cells’ DNA and proteins that help to dial gene activity up or down. For fat cells, the shift in gene activity seems to render them incapable of their normal function. This impairment, as well as the changes in gene activity, can linger long after weight has dropped to healthy levels, a study published today in Nature reports.

The results suggest that people trying to slim down will often require long-term care to avoid weight regain, says study co-author Laura Hinte, a biologist at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. “It means that you need more help, potentially,” she says. “It’s not your fault.”

Although we’ve long known that the body tends to revert to obesity after weight loss, “how and why this happens was almost like a black box”, says Hyun Cheol Roh, an epigenome specialist at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis who studies metabolism. The new results “show what’s happening at the molecular level, and that’s really cool”.

A lingering memory

To understand why weight can pile back on so quickly after it is lost, Hinte and her colleagues analysed fat tissue from a group of people with severe obesity, as well as from a control group of people who had never had obesity. They found that some genes were more active in the obesity group’s fat cells than in the control group’s fat cells, whereas other genes were less active.

‘Epigenetic’ editing cuts cholesterol in mice

Even weight-loss surgery did not budge that pattern. Two years after the participants with obesity had had weight-reduction operations, they had lost large amounts of weight — but their fat cells’ genetic activity still displayed the obesity-linked pattern. The scientists found similar results in mice that had lost large amounts of weight.

In the fat cells of both humans and mice, the genes dialled up during obesity are involved in spurring inflammation and fibrosis — the formation of stiff, scar-like tissue. The genes that are turned down help fat cells to function normally. Research on mice traced these shifts in gene activity to changes in the epigenome, which has a powerful effect on how active a gene is, including whether it is turned on at all.

The scientists tested the durability of these changes by putting obese mice on a diet. A few months after the mice had become lean again, the changes in their epigenomes persisted, as if the cells ‘remembered’ being in a body with obesity.

Rapid regain

It’s not clear how long the body remembers obesity for, says study co-author Ferdinand von Meyenn, an epigenome specialist at ETH Zurich. “There may be a time window when this memory will be lost,” he says. “But we don’t know.”

To better understand the effects of this memory, the researchers studied fat cells from mice that had slimmed down after being obese. These cells absorbed more sugar and fat than did fat cells from control mice that had never been obese. The formerly obese mice also gained weight faster on a high-fat diet than control mice did.

Obesity drugs aren’t always forever. What happens when you quit?

But scientists not involved in the study, including Roh, note that the paper doesn’t prove that the epigenetic alterations caused the physical changes in the mice. The paper’s list of epigenetic alterations in fat cells is valuable, says biologist Evan Rosen at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, who studies fat tissue, but it will be difficult to determine which of those changes drive the fat cells’ lingering memory.

“It’s not yet a causal link,” agrees von Meyenn. “It’s correlation. … We’re working on this.”

Preventing obesity to begin with is key, von Meyenn adds. People who lose weight “can [stay] lean, but it will require a lot of effort and energy to do that”, he says, adding that his team’s findings could help to remove some of the stigma surrounding obesity.