Rapa Nui is known for its giant stone figures, called moai.Credit: Sébastien Lecocq/Alamy

More than 800 years ago, Polynesians sailed thousands of kilometres across the Pacific Ocean to one of the most remote islands on Earth, Rapa Nui.

Now, a study of ancient genomes from descendants of these voyagers has answered key questions about the island’s history, dispelling the idea of a population collapse hundreds of years ago, and confirming precolonial contact with Indigenous Americans.

Ancient voyage carried Native Americans’ DNA to remote Pacific islands

The theory that the early Indigenous inhabitants of Rapa Nui — also known as Easter Island — ravaged its ecosystem and caused the population to crash before the arrival of Europeans in the early eighteenth century was popularized in the 2006 book Collapse, by geographer Jared Diamond, but some other scholars have since criticized that theory.

The latest analysis, published on 11 September in Nature1, “serves as the final nail in the coffin of this collapse narrative”, says Kathrin Nägele, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. “It’s correcting the image of Indigenous people.”

The study was done with the endorsement of and input from officials and Indigenous community members in Rapa Nui. The authors say that their data could contribute to the repatriation of the remains sampled in the study, which were collected in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and sit in a Paris museum.

Answers from DNA

After settling Rapa Nui by around ad 1200, ancient Polynesian people developed a flourishing culture famous for its hundreds of colossal stone statues, called moai.

When Europeans first reached the island in 1722, they estimated that it had a population of between 1,500 and 3,000 people and found a landscape denuded of the palm-tree forests that would have once covered the island. By the late nineteenth century, the Indigenous population, called the Rapanui, had dwindled to 110 people, owing to a smallpox outbreak and the kidnap of one-third of the inhabitants by Peruvian slave traders.

The ‘ecocide’ theory, that a pre-contact population of 15,000 or more plundered the once-pristine island’s resources, has been challenged by researchers who have questioned humans’ role in deforestation and its effects on food production, as well as the large estimates for the population.

Indigenous groups look to ancient DNA to bring their ancestors home

Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, a population geneticist at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and Víctor Moreno-Mayar, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Copenhagen, were hopeful that ancient Rapanui DNA could address the ecocide theory, as well as another lingering question: when ancient islanders mixed with Native Americans.

Their team’s 2014 study of genomes from contemporary Rapanui identified that these people had some Native American ancestry that seemed to have been acquired before European arrival2, hinting at voyages to the Americas. But a 2017 study found no signs of Native American ancestry in the genomes of three individuals people who lived in Rapa Nui before 17223.

To find answers, the researchers turned to human remains in France’s National Museum of Natural History that were collected in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Genome sequences from the teeth or inner-ear bones of 15 individuals, and comparisons with other ancient and modern populations, suggested they were Rapanui, and radiocarbon dating showed that they lived between 1670 and 1950.

No population collapse

Both ancient and modern genomes carry information about how a population’s size has changed over time. When the population is small, segments of DNA shared between individuals — which are inherited from a common ancestor — tend to be longer and more abundant, compared with DNA segments from periods when numbers are higher.

In the genomes of the ancient Rapanui, there were signs of a population bottleneck around the time the island was settled, as would be expected when a founder group arrives. But after that, the island’s population seemed to grow steadily until the nineteenth century.

Divided by DNA: The uneasy relationship between archaeology and ancient genomics

Translating these trajectories into actual population numbers is not straightforward, but further modelling suggested that the genetic data are not consistent with, for example, a drop from 15,000 to 3,000 people before the eighteenth century. “There’s no strong collapse,” says Malaspinas. “We’re quite confident that it did not happen.”

All the ancient Rapanui carried Native American ancestry in their genomes, which the researchers determined had probably resulted from mixing dated to the fourteenth century. The Native American segments most closely resembled DNA from ancient and modern-day inhabitants of the central Andean highlands in South America, but the dearth of ancient and modern human genomes from the Americas makes it impossible to pinpoint the people the ancient Rapanui encountered, adds Moreno-Mayar. Still, the finding that Rapanui encountered Native Americans hundreds of years before Europeans arrived is “a banger result”, says Nägele. “We can look for where this happened and who travelled.”

Community input

Keolu Fox, a genome scientist at the University of California, San Diego, says the finding that Rapanui reached the Americas will come as no surprise to Polynesian people. “We’re confirming something we already knew,” he says. “Do you think that a community that found things like Hawaii or Tahiti would miss a whole continent?”

The researchers received a similar reaction when presenting their initial findings in Rapa Nui. Malaspinas recalls being told that ‘of course we went to the Americas’. She, Moreno-Mayar and other colleagues made multiple trips to the island to consult with officials and residents throughout the study.

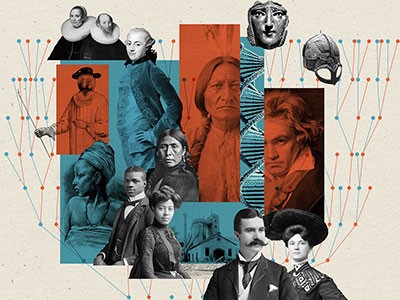

From Vikings to Beethoven: what your DNA says about your ancient relatives

Malaspinas and her colleagues got approval for the study from committees that oversee land use and cultural heritage on the island. The researchers sought their permission after sampling the remains in Paris — something Malasipinas now regrets. “I would do things differently if I had started the project today,” she says, adding that her team was prepared to shelve the work if the committees had said no.

Community outreach in Rapa Nui shaped the questions the project tackled, says Malaspinas, such as trying to settle the relationship between ancient and present-day Rapanui. There was also a strong interest in repatriating the remains, something the researchers hope will eventually happen.

Nägele, who works in Polynesia, thinks the researchers did a good job of engaging with people in Rapa Nui. But she adds that scientists should have a stronger role in pressuring foreign institutions to return Indigenous remains to their place of origin.