Between an unrelenting itch that interrupts sleep and the social challenges of rashes that can appear anywhere on the body without warning, atopic dermatitis has many ways of raising a person’s stress levels and affecting their mental health. “It’s so obvious that these patients suffer. You really have to be a poor clinician or very unskilled observer not to see it,” says Jacob Thyssen, a dermatologist and researcher at the Copenhagen University Hospital. Over the past two decades, data gleaned largely from health records and surveys have revealed associations between the inflammatory skin disease, which affects up to 25% of children and up to 10% of adults, and a wide variety of neuropsychological diagnoses. The most common of these are anxiety and depression, but they also include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), cognitive and behavioural changes, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and alexithymia, difficulty in recognizing and expressing emotions1.

The link between atopic dermatitis and mental health has consistently been borne out in studies and in clinics. Indeed, the increase in the risk of depression for adults with this skin condition has been found to range from 14% to 20% compared with people who do not have atopic dermatitis1,2.

Nature Outlook: Skin

It makes intuitive sense that a visible disease such as atopic dermatitis — the most common form of eczema — could contribute to depression or anxiety by limiting an individual’s social confidence. It’s also rational to conclude that chronic itch could contribute to symptoms that lead to an OCD or ADHD diagnosis. But many dermatologists and researchers think that there is more to it than that, and hope to gain a deeper understanding of the biology that mediates these connections.

Over the past eight years, the availability of highly effective systemic drugs for atopic dermatitis has permitted studies that have shown that when the disease is under control, anxiety and depression symptoms recede. This has been confirmed in retrospective studies of people receiving a monoclonal antibody therapy called dupilumab, which targets an inflammatory cytokine, called interleukin-4 (IL-4)3. “When you interrupt these inflammatory pathways, these patients improve in many domains: anxiety, sleep, depression, overall quality of life,” says Brian Kim, a dermatologist and neuroimmunologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

It’s unclear whether systemic therapies improve mental health just by healing the skin or because they target some of the biological mechanisms that purportedly link atopic dermatitis to neuropsychology. These potential mechanisms, including sleep disruption and neuroinflammation, “are not very well characterized”, says Joy Wan, a paediatric dermatologist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. It’s also possible that atopic dermatitis shares genetic risk factors with some neuropsychiatric conditions, which are also associated with inflammation and poor sleep.

Realizing that these relationships are not easily disentangled, dermatologists continue to study the impacts of atopic dermatitis on mental health and quality of life. The search for biological mechanisms, meanwhile, could help to clarify the links to neurodevelopmental conditions, such as ADHD, which scientists agree needs more research, and broaden our understanding of how the brain processes itch.

Cause and effect

Searching for causal relationships between conditions that are individually complex is no easy feat. In the case of atopic dermatitis and the assortment of mental-health conditions that often accompany it, confounding variables abound. For example, Thyssen says, someone with severe atopic dermatitis might be reluctant to see friends or to pursue new relationships or hobbies. In a later diagnosis of depression, it’s hard to distinguish the role of those kinds of behavioural change from that of skin-disease biology.

Long-term studies that monitor participants’ data over years of treatment can help to untangle whether atopic dermatitis symptoms contribute to or simply share risk factors with neuropsychiatric outcomes, says Amy Paller, a dermatologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois. It’s clear that highly effective treatments for atopic dermatitis, including dupilumab, can reduce neuropsychological symptoms that already exist.

Now, there is evidence that these drugs might also help to prevent mental-health conditions from developing. A retrospective cohort study published in March, for example, monitored people with atopic dermatitis who were taking either dupilumab or conventional (non-immunotherapeutic) drugs for three years, excluding anyone with a previous neuropsychiatric diagnosis. The study found that people on dupilumab were 24% less likely to develop anxiety and 30% less likely to develop depression than were those taking conventional drugs, showing that a highly effective treatment targeting atopic dermatitis affected later development of mental-health issues4.

In a study published this year, Wan and her colleagues examined the rates of learning disabilities and psychiatric diagnoses, including behavioural, mood, sleep and anxiety disorders, among children with atopic dermatitis who had been prescribed dupilumab. Over a two-year period, the children taking dupilumab were, on average, 44% less likely to acquire a psychiatric diagnosis than children with atopic dermatitis who received other types of therapy5.

Neither study, however, compared the treatment approaches’ effectiveness at reducing atopic dermatitis symptoms. That makes it difficult to draw a direct line between the symptoms of the skin disease and development of later neuropsychological conditions.

With dupilumab approved in children as young as six months old, Paller says, there is now an opportunity to test whether early intervention with severe atopic dermatitis can reduce the risk of developing a variety of related conditions over the course of childhood. Paller is part of an international study called PEDISTAD, in which researchers are following the health of 1,845 children aged 0–11 with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Over a ten-year period, the study will track which medications the children take for their skin disease, and how many of them develop other atopic conditions, including food allergies and neuropsychological conditions, such as ADHD. “Being able to track that over time is going to be an eye opener,” Paller says.

Sleep on it

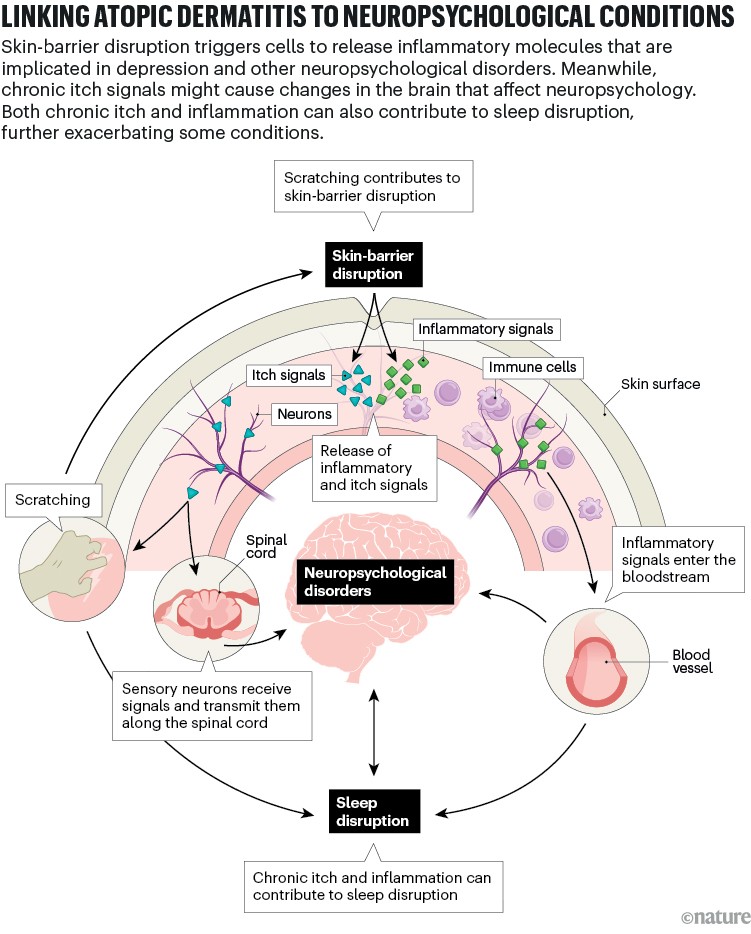

Although the directionality of the relationships between atopic dermatitis and various neuropsychological conditions remains murky, researchers hope to find clarity by pinpointing the biological mechanisms involved (see ‘Linking atopic dermatitis to neuropsychological conditions’). “One of the most well-studied and highlighted potential mediators is sleep,” Wan says.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

People with atopic dermatitis are two to four times more likely to experience sleep disturbances, which include anything from difficulty falling asleep to insomnia or sleep apnea, than are people without the skin condition6. The rate of sleep disturbances also increases as atopic dermatitis symptoms get worse.

This association is key because poor sleep is a risk factor for various neuropsychiatric conditions, including anxiety and depression, and for behaviours associated with ADHD, such as low impulse control7. Sleep problems are common among people with alexithymia and OCD, and sleep seems to play a key part in the link between atopic dermatitis and ADHD.

Paller worked on a study published in 2016 that stratified children’s health data on the basis of whether they regularly got at least four nights of adequate sleep per week. The researchers found that the odds of having an attention deficit disorder or ADHD diagnosis were two to five times higher for children in the low-sleep group, depending on the severity of their atopic dermatitis8.

Wan and her colleagues examined more than 30,000 electronic health records spanning 20 years to look for relationships among atopic dermatitis, sleep disorders and neuropsychological conditions in people under 18. The researchers compared the rates of diagnoses of ADHD, anxiety, depression and learning disorders in the five years after participants were diagnosed with a sleep disorder. Their key finding was that, in the absence of atopic dermatitis, having a sleep disorder increased the risk of developing a neuropsychiatric disorder by 1.7-fold to 2-fold. Among children with atopic dermatitis, the impact of sleep disorders was more profound, leading to a 2.4-fold to 2.7-fold higher risk of being diagnosed with a neuropsychiatric condition.

These results, published in February, suggest that although poor sleep might be a mediator between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric conditions, there might also be an extra interaction between the skin disease and sleep problems9. “Somehow there is this modification or statistical interaction between atopic dermatitis and sleep disorders on the subsequent development of these neuropsychiatric conditions,” Wan says.

Wan is now taking a closer look at how atopic dermatitis severity and poor sleep might translate into neuropsychiatric diagnoses. She and her colleagues will test how sleep disruptions affect neurocognition in children with the skin condition by assessing executive functioning skills, cognition and emotional regulation. She hopes to clarify which symptoms of atopic dermatitis lead to increases in neurodevelopmental diagnoses. “Is it truly ADHD that we might be more likely to detect in children with atopic dermatitis, or is it that they’re very itchy, literally itchy in their skin, and it’s hard for them to stay still?”

In his own clinic, Thyssen has seen big differences in children’s behaviour before and after successfully treating their atopic dermatitis. “You see how they cannot sit still. They are climbing on the walls in your clinic while you talk to their parents,” he says. Until their skin condition is sufficiently treated, he says, he struggles even to attain eye contact with many of his elementary-school-aged patients.

Dermatologists are studying the impacts of atopic dermatitis on mental health.Credit: Ana Alves/Alamy

Wan says that more work is needed to distinguish whether atopic dermatitis exacerbates existing neurocognitive conditions, or causes symptoms that could be mistaken for inattention, hyperactivity or other features of ADHD. “Some of those details still need to be really looked at with more robust studies,” she says.

Atopic dermatitis is known for being the first in a line of commonly associated conditions called the atopic march, which includes food allergies and asthma. The biological mechanisms behind this progression are not well understood, Paller says, but it is clear that they all involve an inflammatory pathway called type 2 immunity — a suite of immune cells and cytokines that the body typically calls upon to fight off parasites. Type 2 immunity is notorious for its involvement in allergies, activating histamine-producing mast cells that lead to temporary conditions such as itchy eyes and a runny nose. The chronic itch of atopic dermatitis is mainly caused by type 2 immune cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, that trigger sensory neurons in the skin, both of which signal through the IL-4 receptor.

Itch on the brain

People with atopic dermatitis tend to have higher levels of type-2-related cytokines in their blood, and some scientists have proposed that system-wide inflammation might also affect the brain. “If you have increased systemic inflammation, that may also influence neuroinflammation, which has emerged as a potential driver of neuropsychiatric conditions,” Wan says. That’s a reasonable hypothesis. After all, type-2-immunity pathways in the brain help to regulate cognition, learning and recovery from injury. Levels of some type 2 cytokines are higher in the blood of people with depression and stress, and anxiety can enhance type 2 immunity.

Although the dots connect in theory, Wan says that direct evidence for an immune-mediated association between atopic dermatitis and brain function is scant. A 2019 study10 reported that treatment with dupilumab brought down the levels of several type-2-related cytokines in the blood of people with atopic dermatitis. However, no studies have looked at blood cytokine levels and changes to neuropsychiatric disorder risks in the same group of people with atopic dermatitis.

Then again, perhaps inflammatory cytokines don’t need to reach the brain to have an effect on mood. In 2017, a team led by Kim described the interactions between the immune and nervous systems in the skin that produce signals that are eventually processed in the brain as itch11. Now, Kim wants to know whether those local interactions are sufficient to affect mental health directly. Rather than rashes, embarrassment and chronic itch causing only a conscious awareness that leads to depression or anxiety, Kim suggests that chronic itch itself could be sending signals to the brain, through sensory and spinal-cord neurons, indicating that something is wrong.

There is evidence that chronic itch can cause alterations to the peripheral and central nervous systems. The condition enhances the reactivity and sensitivity of itch-sensing neurons, says Gil Yosipovitch, a dermatologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida. He and others have done brain-imaging studies that have revealed that many of the brain regions activated by itch are also implicated in neuropsychiatric conditions.

More from Nature Outlooks

Although direct evidence is still lacking, Yosipovitch suspects that cascades of inflammatory signals can reach the brain indirectly, possibly through the nervous system, contributing to functional and structural changes that have neuropsychological effects. In his clinical experience, he’s noticed that many people with the inflammatory skin disease psoriasis, which is also associated with heightened rates of depression, experience improvements in mood shortly after starting on a monoclonal antibody drug — well before their skin disease clears up. The drug, called secukinumab, blocks the cytokine IL-17, which is implicated in depression.

In March, Yosipovitch’s group published a study12 showing that within a month of starting secukinumab, ten people with psoriasis had reduced cortical thickness in two areas of the brain associated with itch. By contrast, increases in cortical thickness in one of these regions have been observed in people with depression and anxiety. Yosipovitch says he would not be surprised to see similar changes in the brains of people taking systemic drugs for atopic dermatitis, although no such study has been done.

Kim and his colleagues have started using animal models to more directly test his idea that chronic itch signalling through the nervous system can affect mood and cognition. Using a process called chemogenetics, the researchers selectively activate genes in itch-responsive brain regions in rodents, and then watch for behavioural changes. Kim also wants to test whether the same processes could be at work in organs besides the skin. “Maybe what itch is actually teaching us is how we sense cues from tissues across the board,” he says. All internal organs are innervated by sensory nerves, he says, and not much is known about what those nerves do. “There might be hundreds of diseases where you have organ dysfunction that could send cues to the brain to mediate all these other problems, related to mood, cognition, attention,” Kim says.

Whatever the mechanism linking the disease to neuropsychology, dermatologists need to keep mental health in mind. “When we treat skin disease, it’s not really just about treating the skin,” Wan says, but rather the whole person, their family and their quality of life.