Ethics approval

Human subjects research approval was obtained (University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics (Medical) Committee Clearance Certificate No. M170880, M2210108), and ethics approvals were also obtained at each study centre. Informed consent was obtained from participants for all samples collected. Every participant was provided with an information sheet and consent documents, either in English or translated into the local language. Participants had opportunities to discuss concerns with the interviewer, and participants who could not read or write had documents read aloud with a witness31. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board deemed that the de-identified data transferred to Stanford University do not constitute human subjects research and thus did not require a further ethics approval beyond the human subjects research approval obtained at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Community engagement

Each study centre conducted pre-study engagement before recruitment during both AWI-Gen 1 and AWI-Gen 2, adapting to the local contexts to engage with community members and discuss feedback and concerns related to the study. For example, in DIMAMO, South Africa, pre-study engagement involved meeting with tribal leaders, the community advisory team and community representatives. In Navrongo, Ghana, the community engagement team visited chiefs and elders of the various study communities and informed them of the proposed study, and followed up with a community sensitization gathering before AWI-Gen 1 with a larger audience of chiefs, elders and people of the study communities. The community durbar was excluded from AWI-Gen 2, because of the continuing COVID-19 outbreak. In Nairobi, Kenya, the community engagement team held several consultative meetings with members of the community advisory committee, village elders, community health volunteers and AWI-Gen study participants before, during and after the study. The village elders and community health volunteers were crucial in mobilizing study participants who could not be reached by telephone. Questions from participants were related to how blood and stool samples would be used and why the study was focused on women. If during recruitment and sample collection there were notable health concerns28 (for example, hypertension), the participants are referred into their clinical health-care service infrastructures. These mechanisms and processes varied from country to country and for sites within a country, depending on resources and local context.

Study design and cohort selection

Inclusion criteria included previous participation in the AWI-Gen 1 study28 and continued participation in the AWI-Gen 2 study. This AWI-Gen 2 microbiome study is a companion study to an AWI-Gen 2 menopause study, and so only participants self-identifying as female were surveyed for the microbiome sub-study. A small number of men were recruited owing to a fieldwork mix-up. Given the understudied nature of these populations, we did not fully exclude samples from men in downstream analyses; rather, samples from men were excluded from site comparisons and disease associations, but included when cataloguing genomic novelty. Participants were chosen semi-randomly from the overall AWI-Gen 2 participant pool, with extra measures taken to ensure a cross-section of individuals with respect to menopause status and hypertension. See Supplementary Methods for extended recruitment details.

A harmonized approach for stool sample collection was implemented in all study sites to ensure equal temperature exposures and handling of all samples. In Soweto, Nairobi and Nanoro, participants came to central locations for interviews and biomarker collection. Participants were given stool sample collection kits that were either collected the same day or collected from their homes or at a central location in the following days. At the Navrongo, DIMAMO and Agincourt study centres, participants were visited in their homes for interviews and biomarker collection. Participant phenotype data and survey information were stored in REDCap servers based in South Africa, Burkina Faso, and Ghana (v.9 to v.13, regularly updated through the course of the study). Participants were given a stool sample collection kit to use at their home, which was collected by fieldworkers within 24 h.

Each participant self-collected a single stool samples using an OMNIGene GUT OMR-200 Collection Kit (DNA Genotek). This preservation kit maintains DNA integrity and taxonomic composition across a wide range of ambient temperatures81, including the temperatures that are experienced year-round at each of the study sites. Samples were immediately frozen at study centres and then collectively shipped frozen to a central laboratory in Johannesburg, South Africa, where they were thawed, aliquoted into cryovials and stored at −80 °C. After obtaining necessary exportation and importation permits, all samples were shipped on dry ice in a single shipment to the United States for downstream processing. Samples were thawed once more to retrieve aliquots for DNA extraction. We previously conducted analysis to ensure that storage and shipping conditions would not significantly affect measured microbial composition81. Altogether, this approach minimized any technical confounders that would have coincided with study site, and we do not anticipate any other site-level methodological variation that would affect sample composition. Participant metadata, including age, demographic information, health history and blood biomarkers were collected as part of the larger AWI-Gen 2 project, with methods similar to those used in AWI-Gen 1 (ref. 31).

DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing

All stool samples were extracted at the same time, in the same facility to minimize batch effect. DNA was extracted from samples using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen, catalogue no. 51804) from 300 µl of stool sample according to manufacturer’s instructions. Bead beating was performed for 10 min at 30 Hz, followed by rotation of the adapter and an extra 10 min of bead beating using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, catalogue no. 85300) using a 2-ml Tube Holder Set (Qiagen, catalogue no. 11993), and DNA extractions were eluted with C6 Elution Buffer in a final volume of 80 µl. DNA concentration was quantified by spectrophotometer using the DropSense 96 platform (Trinean, catalogue no. 10100096). Every extraction batch of 96 samples included one water blank as a negative control and one mock community aliquot (Zymo Research, catalogue no. D6300) as a positive control.

All libraries were prepared concurrently at the same facility and sequenced at the same time across several flow cells. Samples were evaluated for concentration, integrity and purity before library preparation using the 5400 Fragment Analyzer System (Agilent, catalogue no. M5312AA). Metagenomic libraries were prepared using the NEB Ultra II kit (NEB, catalogue no. E7645L) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Library concentration was quantified using quantitative polymerase chain reaction and fragment length distribution was analysed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, catalogue no. G2939BA). Libraries were pooled and 2 × 150-base-pair reads were generated using the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, catalogue no. 20012850).

Metagenomic read preprocessing and taxonomy profiling

Metagenomic reads were deduplicated using HTStream SuperDeduper v.1.3.3 with default parameters, trimmed using TrimGalore v.0.6.7 with a minimum quality score of 30 and a minimum read length of 60. Reads aligning to version hg38 of the human genome were removed using BWA v.0.7.17 (ref. 82). Metagenomic reads were taxonomically profiled using mOTUs v.3.0.3 (ref. 83) and counts were distributed to GTDB84 species using the GTDB_v207 mapping file available as part of the mOTUs database.

Given the number of previously unknown bacterial taxa observed in our assembly approach (see below), we aimed to better characterize the taxonomic composition by including our assembled bacterial genomes into the mOTUs database. To do so, we extended the mOTUs database with the scripts available under https://github.com/motu-tool/mOTUs-extender/. In brief, marker genes were identified in all high-quality assembled genomes using fetchMG v.1.2 (ref. 85). Those genes were then clustered together with the genes in the mOTUs database v.3.0.3. The resulting extended database contained 662 new genome clusters and reduced the fraction of unassigned reads for nearly all samples. Particularly in samples from Nanoro and Navrongo, the new genome clusters carried a large part of the relative abundance (Extended Data Fig. 3). For GTDB-level profiling, the GTDB-tk classification of our assembled genomes were added to the GTDB_v207 mapping file. Unless indicated otherwise, all analyses shown here are based on the extended mOTUs database.

All samples were used for metagenome assembly and new feature discovery (n = 1,820). Samples from males, one sample with a potential label mismatch, and samples with high percentages of human reads (percentage of human reads more than or equal to 70%, n = 4 samples) were excluded from classification-based analyses and site comparisons, leaving 1,796 samples for other analyses.

Participant covariate processing

Extensive participant data were collected as part of the AWI-Gen study, including demographic, ethnolinguistic, family composition, pregnancy, cognition, frailty, household amenity, substance use, general health, diet, infection history, cardiometabolic disease and physical activity information. Participants also gave blood, urine and stool samples, and underwent ultrasound, blood pressure, blood and urine testing for various metrics. Not all data were available for every participant, and some participants gave stool samples for microbiome analysis but did not complete other testing or questionnaires. At the time of analysis for the microbiome study, not all participant data had gone through quality control. In total, 59 variables were available to use as covariates in the microbiome study.

Before using covariate data in microbiome analysis, we first collapsed the covariate dataset to only those variables that we expected to be most meaningful to avoid unnecessary multiple-hypothesis testing and measuring associations between dependent variables. First, we removed variables that had overwhelmingly missing data, excluding those that had entries for 100 or fewer participants (for example, several ultrasound measurements). Second, we filtered variables with not enough unique values (such as sex, which had only one group). Lastly, we excluded variables with an entropy (calculated with the infotheo package v.1.2.0.1 (ref. 86) in R) of less than 0.2 to avoid variables that were too uniform in the participant set to power comparisons (for example, breast cancer or cervical cancer status with only 10 and 12 cases, respectively).

To calculate correlation between covariates and associations between covariates and microbiome composition, we transformed non-numerical covariates into numerical values on the basis of ordered factor levels. For example, values for the Menopause covariate were changed from Pre-menopausal to 1, from Peri-menopausal to 2 and from Post-menopausal to 3. Most covariates were binary (for example, Probiotics could contain either the value Yes or No) and were converted to 1 (for Yes) and 2 (for No) in this process. The full list of binary variables is: Arthritis, Diabetes status, Diabetes treatment, Hypertension status, Hypertension treatment, Pesticides, Vigorous work, Weekend work, HIV medication, HIV status, Cattle, Other livestock, Potable water, Poultry, Refrigerator, Toilet, Deworming treatment, Probiotics, Chew tobacco and Smokeless tobacco. The variables describing time (Deworming period, Probiotics period, Antibiotics and Diarrhoea last) were ordered according to recency with the order WithinLastWeek < WithinLastMonth < WithinLastSixMonths < WithinLastYear < WithinLastTwoYears < WithinLastThreeYears < Longer < Never. Employment was ordered as Self-Employed < FormalFull-time < FormalPart-time < Informal < Unemployed. Site density was ordered as Nanoro < Navrongo < DIMAMO < Agincourt < Soweto < Nairobi.

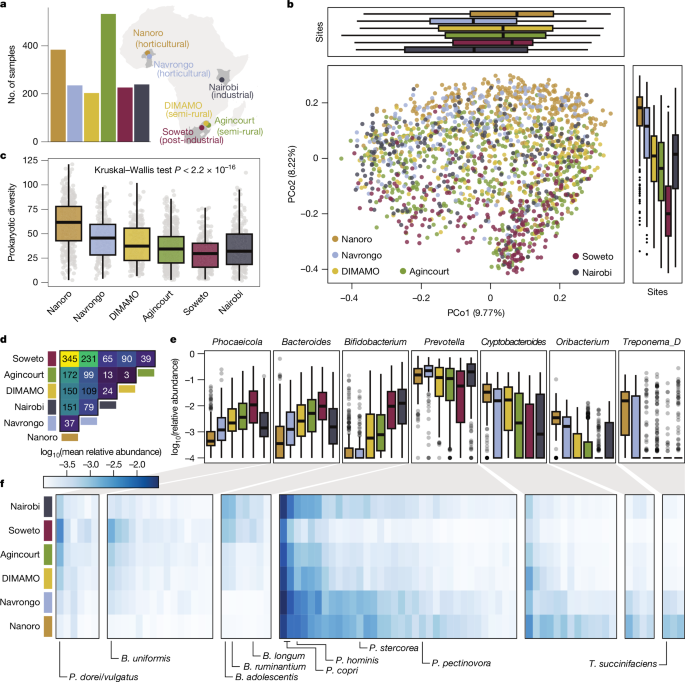

Microbial diversity, composition and site differences

To measure prokaryotic alpha-diversity, species counts were rarefied to 5,000 using the rrarefy function available through the vegan R package v.2.6-4 (ref. 87). Alpha-diversity was measured as inverse Simpson index after rarefaction, and prokaryotic richness was measured as number of species with relative abundance greater than or equal to 1 × 10−4 after rarefaction).

Beta-diversity was calculated on the Bray–Curtis distance using the vegdist function from vegan87 and the pco function from the labdsv R package v.2.1-0 (ref. 88). To assess the amount of variance explained by covariates, we undertook distance-based redundancy analysis with the dbrda function from vegan. In an iterative manner, the covariate explaining the highest amount of variance was added to the model formula. To reduce redundancy of highly correlated covariates, all available covariates were transformed into numerical values (using ordinal factors, whenever applicable) and the Pearson correlation between covariates was calculated. In cases of highly correlated covariates (Pearson’s r ≥ 0.8), the covariate that explained the higher amount of variance in the prokaryotic composition was chosen for the iterative model (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Prokaryotic species prevalence was defined as the fraction of individuals in a study site in which a given species is found at a relative abundance of more than or equal to 1 × 10−4. The difference between sites for individual taxa was calculated using a generalized fold change89. In short, instead of comparing the median (the 50% quantile) between distributions, the generalized fold change is the mean of the differences between two distributions at several quantiles and can therefore resolve differences also in low-prevalence taxa. Figure 3d shows the number of taxa for which the generalized fold change between sites exceeds the 90% quantile of all pairwise site comparisons across all prokaryotic species.

The number of samples for these analyses (Fig. 1 and associated supplements) was distributed across the different sites as follows: Nanoro, n = 382; Navrongo, n = 218; DIMAMO, n = 201; Agincourt, n = 532; Soweto, n = 226; Nairobi, n = 237.

Metagenome assembly and external dataset comparison

All samples (n = 1,820), including samples for male participants, were included in metagenomic assembly analyses (Nanoro, n = 384; Navrongo, n = 235; DIMAMO, n = 203; Agincourt, n = 533; Soweto, n = 226; Nairobi, n = 239). Metagenomic reads were assembled using megahit v.1.2.9 (ref. 90) and assembly quality was assessed using QUAST v.5.2.0 (ref. 91). Metagenomic assemblies were binned into draft genomes using MetaBAT v.2.5 (ref. 92), CONCOCT v.1.1.0 (ref. 93) and MaxBin v.2.2.7 (ref. 94), and subsequently dereplicated and aggregated on a per-sample basis using DAS Tool v.1.1.6 (ref. 95). Bin quality was assessed using CheckM v.1.2.2 (ref. 96). To create a dereplicated genome set, MAGs were dereplicated using dRep v.3.4.3 (ref. 97), filtering to only include genomes with a minimum CheckM completeness of 50% and maximum CheckM contamination of 5%. In dereplication, we implemented a primary clustering threshold (-pa) of 0.9 and secondary alignment threshold (-sa) of 0.95, requiring minimum overlap between genomes (-nc) of 0.3, using multiround primary clustering (–multiround_primary_clustering) and greedy secondary clustering with fastANI v.1.33 (ref. 98) (–greedy_secondary_clustering, –S_algorithm fastANI) to reduce the computational complexity of dereplicating a large genome set. For dereplication, cluster representatives were chosen using scoring criteria that included a completion weight (-comW) of 1, contamination weight (-conW) of 5, N50 weight (-N50W) of 0.5, size weight (-sizeW) of 0, and centrality weight (-centW) of 0. Genome filters and scoring were consistent with standards used in the UHGG50. The final genome set was taxonomically classified and placed in a tree with GTDB-tk v.2.3.0 (ref. 99) using the GTDB r214 catalogue and default parameters. Phylogenetic trees were visualized with iTOL v.6 (ref. 100). The dereplicated prokaryotic genome set was compared against the UHGG v.2.0.1 species representatives using dRep v.3.4.3 with the same parameters as previously stated above.

Protein-coding genes were predicted from each medium-quality and high-quality prokaryotic genome, before genome dereplication, using prodigal v.2.6.3 (ref. 101) with parameters -c -p meta to exclude partial genes. Putative proteins were clustered successively using mmseqs v.14.7e284 (ref. 102) linclust command with alignment coverage (-c) of 0.8 in target coverage mode (–cov-mode 1) and greedy secondary clustering (–cluster-mode 2) at 100% and 95% amino acid identity (–min-seq-id). The 95% identity protein set was compared against the UHGP95 v.2.0.1 proteins using mmseqs v.14.7e284, and proteins sharing 95% amino acid identity over 80% of the UHGG protein were considered to match the UHGP set.

Modelled accumulation of previously unknown prokaryotic genomes and proteins with further participant sampling was determined by randomly subsetting the full participant set or site-specific participant sets to a range of individuals (1–1,500) in 100 iterations and counting the number of prokaryotic genome cluster or protein clusters represented by the participant subset.

Comparison with external metagenomic studies (Extended Data Fig. 7) used the same pipelines for read preprocessing, assembly and binning, with the exception of Carter et al.43 who published a MAG catalogue. All genomes from the UHGG, AWI-Gen 2 and external metagenomic studies were dereplicated using the same parameters as described above.

Treponema succinifaciens core genome analysis and functional profiling

We evaluated the complete set of T. succinifaciens MAGs in our genome catalogue before dereplication. To identify T. succinifaciens genomes, we selected all genomes with completeness of more than 90% and contamination less than 5% that fell into a secondary cluster with genomes classified as Treponema_D succinifaciens by GTDB-tk in our dereplicated genome catalogue (n = 244). Coding sequences were annotated with bakta v.1.8.2 (ref. 103). Core genes, defined here as genes present in at least 80% of genomes, were identified with roary v.3.12.0 (ref. 104).

Public T. succinifaciens genomes with completeness of more than 90% and contamination less than 5% were downloaded from the UHGG50, Carter et al.43 and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). To build a global phylogenetic tree, core genes were identified and incorporated into a core gene multiple sequence alignment using roary v.3.12.0 (ref. 104) and MAFFT v.7.407 (ref. 105). The core gene multiple sequence alignment was used as input to FastTree v.2.1.11 (ref. 106), and the resulting phylogenetic trees were visualized in iTOL v.6 (ref. 100). Phylogeographic signal was statistically quantified using the same method as Hildebrand et al.107: we calculated pairwise phylogenetic distance between all genomes on the basis of branch length using DendroPy108, and implement a permuted multivariate analysis of variance test with 1,000 permutations with adonis2 (ref. 87) to evaluate whether phylogenetic distances within countries are smaller than phylogenetic differences between countries.

Associations between T. succinifaciens presence and host phenotype were performed for all participants from Nanoro, Burkina Faso and Navrongo, Ghana. Host phenotype measurements included antibiotic history, anthropometric measurements, livestock ownership, hypertension status and all biomarkers. Associations were tested using a linear model that adjusted for site and for antibiotic history, excepting the association with antibiotic history, which only adjusted for site. Correction for multiple-hypothesis testing was performed with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Antimicrobial resistance profiling was performed with the Resistance Gene Identifier109, and ‘Loose’ matches were omitted. Carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) annotation was performed on all high-quality MAGs from AWI-Gen 2 using dbCAN3 v.4.1.4 (ref. 110) with the prok parameter for conservative, high-confidence annotations. Substrate annotation was performed at the CAZyme family level using the high-level substrate annotations from the dbCAN3 substrate mapping table, and substrates were grouped according to biological origin.

Viral fraction characterization

Phage genomes were annotated from metagenomic assemblies with VIBRANT v.1.2.1 (ref. 111), and genome quality was determined with checkV v.1.0.1 (ref. 112). Redundant genomes from each sample were removed by clustering medium- and high-quality genomes using a database built with BLAST 2.14.0 (ref. 113), clustering at a minimum of 95% ANI and 85% alignment fraction using checkV supporting scripts with default parameters. Phage richness was measured as the number of assembled phage genomes per sample after removal of duplicate genomes. A unified catalogue of phage genomes was built by clustering the representative phages from each individual using the same clustering parameters, and this catalogue was compared against the MGV v.1.0 (ref. 114) vOTU representative phage genomes using the same BLAST clustering approach and parameters. Alternate phage profiling using read-based classification (Extended Data Fig. 9) was performed with Phanta v.1.1.0 (ref. 115) using the combination of MGV and UHGG as the reference database. Phage richness measured with Phanta was defined as the number of phage species clusters present at greater than or equal to 10−5% relative abundance. Differences between alpha-diversity metrics across sites were tested with a linear model, using the anova function from base R to estimate the significance of the difference. Modelled accumulation of previously unknown phage genomes with further sampling was performed using the same methods as described above for modelled prokaryotic genome and protein accumulation.

Crassvirales and crAssphage prevalence was defined as the fraction of individuals with taxon relative abundance of greater than or equal to 10−5%. Previously unknown jumbophages were defined as viral genomes in the dereplicated genome catalogue with length greater than 200 kb that did not cluster with an MGV vOTU representative. We further filtered the new jumbophages to highlight only jumbophages with evidence supporting prevalence and novelty, by including only those with assembled genomes present in at least five individuals, and with alignment fractions less than 10% against any MGV vOTU representative. Jumbophage genes were annotated with bakta v.1.8.2 (ref. 103). Read-level presence of jumbophages was defined at greater than 0.1 coverage threshold as measured using CoverM v.0.7.0 (ref. 116).

Association between microbiome features and HIV status

Participants from Agincourt, South Africa, Soweto, South Africa and Nairobi, Kenya were included in this analysis. Participants from DIMAMO, South Africa were excluded because of the low number of PLWH (n = 6). Participants from Nanoro, Burkina Faso and Navrongo, Ghana were excluded because HIV status was not measured in these populations owing to a low national prevalence of HIV. A total of 848 participants were included in this analysis, capturing 129 PLWH and 719 seronegative individuals (Table 1 and Supplementary Data 9). The rest of the samples from those sites were either HIV positive, but reported not to take ART (n = 28, n = 22 in Agincourt, n = 3 in Soweto, n = 3 in Nairobi). Male individuals and individuals with missing/discrepant HIV/ART data or with low read counts were excluded. Prokaryotic alpha- and beta-diversity were calculated as described above.

We undertook differential abundance analysis using a linear mixed effect model implemented in the lmerTest R package v.3.1-3 (ref. 117), including site, exposure to antibiotics and self-reported recency of diarrhoea as random effects, because those factors had shown to be related to microbiome composition in the previous analyses. Overall effect size was estimated through the lmerTest package as well and generalized fold change within each site was calculated as described above.

For the machine learning analysis, we trained statistical models using the SIAMCAT R package v.2.5.0 (ref. 89) for both all data combined and for each site separately. In short, relative abundances were normalized using the log.std method in SIAMCAT. Samples were split for five-times repeated fivefold cross-validation (20% of samples were retained for testing and not included in model training) and for each split, an L1-regularized logistic regression model was trained on the training folds, using standard parameters. Model evaluation was performed within the cross-validation (for example, within a site) by applying each model to the respective left-out test fold. The predictions for each sample were averaged across repeats and AU-ROC was calculated with the pROC package v.1.18.2 (ref. 118). For cross-site evaluation, the external data was normalized with the recorded normalization parameters (frozen normalization), all models from the cross-validation were applied to the normalized data, and predictions were averaged again for AU-ROC analysis. For the LOSO analysis, models were trained as described on data from two sites combined (for example, Agincourt and Soweto) and were then applied on the data from the left-out site (Nairobi).

To test the fraction of positive prediction in other sites, we calibrated the model prediction to an internal 5% false positive rate; that is, recorded at which prediction threshold 5% of HIV− samples were incorrectly classified as PLWH. The model trained on all data combined was then applied to the data from Nanoro, Navrongo and DIMAMO to quantify the number of samples that resulted in a prediction above the threshold value.

Viral feature comparison between seronegative individuals, PLWH who are ART-naive, and PLWH who are ART+ was performed using phage relative abundance profiles generated by Phanta. Phage richness was calculated as the number of phage species present at greater than or equal to 10−5% abundance in Phanta profiles, as opposed to using total count of assembled phages, because Phanta abundance profiles have features with sufficient prevalence for differential abundance analysis and machine learning models. Differential feature analysis and machine learning models were performed using the same methods as the prokaryotic analysis above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with R v.4.1.2 using the statistical test specified in the respective Methods section. Correction for multiple-hypothesis testing was performed with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure119 as implemented in the p.adjust function in base R in all analyses where several tests were performed. Plots were generated in R using the packages ggplot2 v.3.4.2 (ref. 120), cowplot v.1.1.1 (ref. 121), pheatmap v.1.0.12 (ref. 122) and tidyverse v.2.0.0 (ref. 123).

Ethics and inclusion statement

All authors of this study fulfilled criteria for authorship inclusion, and researchers from each study centre are represented as authors. Researchers from all institutions were involved throughout the study process. Study centre staff facilitated community engagement sessions, which identified specific community concerns and determined that this study is locally relevant. Roles and responsibilities were agreed upon amongst collaborators before conducting the research. Authors of this study have led formal capacity-building genomics workshops for local scientists during the course of the study (Extended Data Fig. 1), along with further informal training. This study has been approved by local ethics review committees (Methods). Research pertinent to the study centres and led by local researchers has been taken into account in the citations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.