Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet Tate Modern, London. Until 1 June 2025.

As artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots such as ChatGPT reopen fundamental questions about the nature of authorship and creativity, it’s worth looking to the past to find answers about the future. In the 1950s and 1960s, an epoch of rapid social and technological change swept the globe.

New institutions and nations arose from the ashes of the Second World War. The quest to decode secret German military communications resulted in the development of the world’s first electronic computer, Colossus. War-time innovations, such as the use of microwave radiation for radar systems and synthetic nylon fibre for military uniforms, started to find their way into daily life in the form of ovens and clothing fabrics. How artists responded to this moment — when the possibilities opened up by modern technology seemed almost limitless — is the subject of Electric Dreams, a wide-ranging exhibition running until June at the Tate Modern art gallery in London.

The 150-odd pieces of vintage tech art on display explore the emergence of innovative techniques and materials that resulted in an explosion in kinetic and optical art, works that move or give the illusion of movement.

How an AI-powered lion became a teaching tool

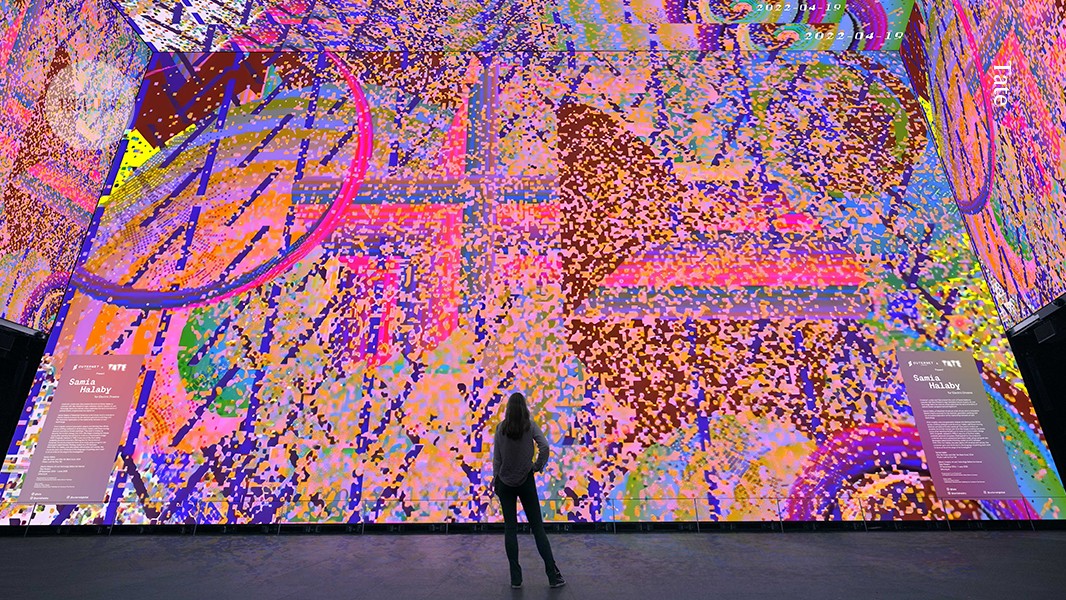

The dawn of modern computing elicited a range of reactions. For visual artist Samia Halaby, the answer was to learn programming to incorporate computer algorithms into her practice as an artist. In an interview with the Tate’s curatorial staff, Halaby recalled seeing images on a computer screen for the first time and thinking, “my paintings are dull compared with this screen”.

Halaby arrived in the United States in the early 1950s after her family was forced to flee their home during the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, just as the world of visual art was coming into contact with modern computing. Computer-generated patterns reminded her of her distant homeland — evoking memories of the geometry of medieval Arabic art. Her paintings from subsequent decades are filled with abstract patterns that pulse with movement.

But some artists were more circumspect about readily adopting information and communication technologies originally developed by the military or corporate entities, using their work to explore the tension between artistic creativity and the cold, logic-based precision of machines.

Artist versus machine

The exhibition opens with artist Vera Spencer’s mesmerizing collage of punched cards. These perforated cards served as the information processing ‘bits’ of early computers. Groups of punched cards sorted into a specific sequence became a ‘program’. When Spencer created her work Artist versus Machine in 1954, such computers were still in use. By reaching into the machine’s innards and stitching its bits into a vibrant, hand-crafted pattern, Spencer wanted to send a message about the value of the human touch. Other artists laboured meticulously to repurpose war-time radar controllers into sketching devices that could create ‘useless’, whimsical patterns.

That spirit of taking back control might well resonate with many twenty-first century artists and writers who view AI systems with deep suspicion. And that is perhaps the ultimate value of this retrospective look. The graphics and motorized components from the mid- to late-twentieth century can seem quaint to the modern eye, but the moral quandary at the heart of these works is timeliness.

Atsuko Tanaka wears her Electric Dress at the 1956 Second Gutai Exhibition in Tokyo.Credit: Tate

In 1956, avant-garde artist Atsuko Tanaka was exploring one such dilemma when she first wore her Electric Dress — a costume modelled after the dazzling neon signs of Osaka, Japan, and made of 200 painted blinking light bulbs. The Tate exhibit of the dress describes how Tanaka thought the bulbs took on an unreal beauty when the electricity was switched on, “as if they were not made by human hands”.

This mid-twentieth-century melding of the Japanese kimono with industrial technology also happened to be incredibly hot and heavy (weighing about 60 kilograms). With so much electricity coursing around her, the dress could have been deadly. Although Tanaka died in 2005, before social media became a dominant cultural phenomenon, her dress can be seen as a metaphor for technology that can dazzle and delight yet also be a source of deep discomfort.

Digital lives

Several other artworks anticipate Internet culture in surprising ways. Liquid Views — Narcissus’ Digital Reflections by Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss from the early 1990s features a digital pool of water that a person can interact with as their reflection is projected on to a large screen, allowing an audience to watch this interaction. In the Greek myth, Narcissus falls in love with his own reflection. Liquid Views was one of the first digital artworks that allowed this type of real-time interaction with one’s own image. Today, selfie culture has turned us all into versions of Narcissus; the camera’s reflected reality is a proxy for self-worth.

The exhibition has an impressively broad geographical range. New Tendencies, an art movement that emerged in the 1960s in Zagreb, Croatia, for instance, saw computer-mediated art as inherently ‘democratic’ because it often enabled audience participation and bridged cultural divides.

Art and science: close cousins or polar opposites?

The art collective Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), based in the United States, joined forces with India’s National Institute of Design after a chance meeting at the 1970 Japan World Exhibition in Osaka (Expo ’70). Together, they launched the world’s first proto chatroom — a network of telex machines, connecting E.A.T. outposts in Stockholm, New York, Tokyo and Ahmedabad, India. Visitors to the chatroom, part of the Utopia: Q&A 1981 exhibition in 1971, could ask questions using interfaces that resembled online messaging boards. The chatroom conversation inevitably turned lewd — one person, for instance, wanted to know how weightlessness would affect lovemaking on the Moon.

What these pre-Internet-era chat transcripts show is that the human response to technological change has remained remarkably similar over time. The purpose of good art is to document this response; to make it tangible; to give structure to fleeting emotions.

As Halaby explains, in her curatorial interview, the best art often emerges during revolutionary times and “uses the technology of its time”. Electric Dreams reminds us that not just computer scientists, but artists, too, can provide visions about what is to come as AI and virtual reality reorder society over the next few decades.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.