Ethics declaration

This research used data from participants in the UKB study for discovery and from the Vanderbilt University’s biorepository of DNA (BioVU) linked to de-identified medical records for replication of specific results. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant in UKB study. The BioVU study was designed as an opt-out biobank. The UKB study received ethics approval from the North West Centre for Research Ethics Committee (no. 11/NW/0382) and the BioVU study from the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board.

Research collaboration framework

This study mainly used WGSs called with DRAGEN 3.7.8 from 490,542 UKB2,3 participants (data field 24310). Further analyses used SNP-array genotypes and imputed genotypes from two reference panels: Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) plus UK10K and TOPMed. This work is the result of a collaboration between teams at Illumina Inc. (UKB application ID 33751) and The University of Queensland (UKB application ID 12505). All WGS analyses were performed under Illumina’s application. All analyses requiring WGS data or SNP-array data imputed with TOPMed reference panel were performed on the DNA Nexus platform, whereas analyses not requiring individual-level data or not cloud-restricted were performed on local computing clusters.

Selection of samples of European ancestry using SNP-array data

The first sample selection was performed using principal component loadings computed from 1000 Genomes (1KG) for 207,965 autosomal SNPs on the 488,377 samples with SNP-array data available and selecting samples within 3 s.d. of the 1KG reference European ancestry population mean for the first 10 principal components (455,516 samples of European ancestry retained). We selected samples having both SNP-array and WGS data available and consenting to data use to have 452,618 samples of European ancestry in the GWAS analyses.

Processing of raw WGS data

We defined stringent quality control steps to ensure high quality of the remaining genotypic information. We first individually processed each one of the 136,477 autosomes chunks of raw Binary Variant Call Format data. In the first step, we kept all samples and removed variants with the following conditions: minor allele count (MAC) < 30, non-‘PASS’ variant and variants with more than 200 alleles. Multi-allelic variants were split into separate rows and long allele names fewer than 100 characters were renamed. We merged each chunk into a single file containing all autosomes variants of MAC > 30 and all WGS samples (about 130 million variants). We then applied a second quality control step, keeping only the European ancestry samples identified previously, normalizing variants on GRCh38 reference genome and applying the following filters: genotype missingness more than 0.1, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P = 10−8 and sample missingness threshold of 0.05. We had a total of \(M_\rmW\rmG\rmS=40,575,204\) SNPs and indels. These samples were used in GWAS analyses. We computed a genomic relationship matrix (GRM) for these 452,618 samples from 583,191 genotyped SNPs of MAF > 0.01. We extracted a sparse GRM with non-zero entries for pairs of relatives with a genomic relationship coefficient (calculated as an allelic correlation, equation (1)) above 0.05 and used it to estimate pedigree-based heritability. We also extracted a set of 347,630 unrelated European ancestry samples for the GREML analyses for which we generated a new set of WGS genotypes. Finally, we computed allele frequencies from the full 452,618 set and the LD scores from the smaller 347,630 set with a block size of 1 Mb and an overlap of 500 kb between blocks.

Grouping variants for GREML-LDMS and covariates processing

To compute MAF and LD partitioned GRMs, each variant was assigned in one of four MAF (0.01–0.1%, 0.1–1%, 1–10%, 10–50%) and further assigned an LD bin (on the basis of the median LD score statistic within each MAF bin) (Supplementary Table 2). LD score statistics were calculated for each SNP as the sum of squared correlations between allele counts at that SNP and that of all nearby SNPs within a 1-Mb window. Sample relatedness between individuals i and k was computed using the following estimator47:

$$A_ik=\frac1M\mathop\sum \limits_j=1^M\frac(x_ij-2p_j)(x_kj-2p_j)2p_j(1-p_j)$$

(1)

where xij is the minor allele count at SNP j for individual i, M the number of variants used to quantify relatedness and pj the MAF at SNP j.

As a secondary analysis, we further quantified the contribution to trait heritability from ultra-rare variants (MAF < 0.01%) by including an extra GRM in both our GREML and HE analyses. Given that unrelated individuals are unlikely to share ultra-rare variants, this extra GRM was assumed to be diagonal (in fact, it is diagonal dominant) with diagonal elements (Dii for individual i) calculated as

$$D_ii=\frac1M\mathop\sum \limits_k=1^K\fracN(N-2k)S_ik+k^2M_kk(N-k/2)$$

(2)

In equation (2), M = 760,525,073 denotes the total number of ultra-rare variants, Mk the number of ultra-rare variants found in exactly k out of N individuals and Sik is the number of variants of count k in the sample (for example, number of singletons when k = 1) that individual i carries. We show in Supplementary Note 3 how equation (2) can be derived from equation (1).

Phenotypes and covariates quality control

From the initial set of 40 million variants, we computed a set of genotypic principal components for each MAF/LD bin independent variants. Parameters for LD pruning was a window of 1 Mb and a R2 = 0.1 for variants of MAF > 0.01 and R2 = 0.01 for MAF < 0.01. In total, 325,484 common variants and 2,435,866 rare variants were retained and 30 genotypic principal components for each bin (that is, 8 × 30 = 240 principal components in total) were computed in the set of unrelated samples using the randomized matrix algorithm implemented in PLINK2 (ref. 48). To obtain genotypic principal components for the full sample set, we computed the loading for each variant then projected them for a per-sample score. For samples included in both sets, the mean correlation between computed and projected genotypic principal components was more than 0.999, with the minimum correlation at 0.982.

We included as base covariates sex, year of birth, assessment centres, fasting time at blood sample collection, month of assessment and prescription drug usage. For the drug usage information, we extracted the field 20003 of the UKB, mapped it to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification codes and grouped in large categories (statins, diuretics, anti-hypertensive, beta-blockers, calcium blockers, angiotensins)49. Furthermore, we also grouped individuals on the basis of their north and east birth coordinates (UKB fields 129 and 130) with a k-means clustering, with different numbers of clusters (10, 20, 50, 100). Individuals with missing birth location (typically, those born outside the United Kingdom) were grouped into a separate cluster. All fasting times greater than 24 h were merged into a single group. Similarly, missing data for assessment centres and month of assessment were grouped into distinct groups. We binarized each of these sets of covariates including each possible year of birth, dropped unused levels for each phenotype and standardized each covariate to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. To reduce data dimensionality (and reduce collinearity), we applied a singular-value decomposition on the covariate matrix from which we selected the top singular vectors associated with eigenvalues explaining in total greater than 99% of the total variance.

Phenotypes were selected on the basis of data availability and clinical relevance. Phenotypes were standardized within each sex to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. For quantitative traits, samples with phenotypic values above 6 s.d. were excluded. Further specific quality control procedures were performed on a trait-dependant basis (Supplementary Table 3).

For each of the 41 phenotypes, we generated 5 sets of covariates on the basis of the singular-value decomposition of the base covariates, the base covariates and principal components, the covariates principal components and the 4 different numbers of k-means-based birth clusters. In total, we fitted as covariates the singular-value decomposition of six different sets of covariates, generated on either the unrelated or full (related) sets of samples.

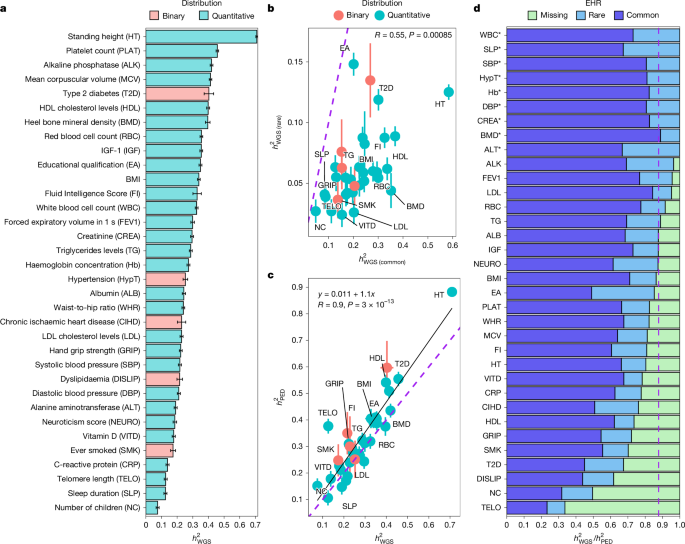

GREML-based estimates

After generating several sets of covariates and/or phenotypes, we used MPH18 to obtain GREML and Haseman–Elston (HE) regression heritability estimates. HE estimates were obtained by initializing all variance components to 0 (except the residual variance initialized to 1) then performing one iteration of the minimum norm quadratic unbiased estimation implemented in MPH18, which is equivalent to HE regression and allows a proper adjustment for covariates. Our primary analyses used GRMs calculated for each of the eight MAF/LD groups of SNPs and several sets of covariates. Analyses aiming at partitioning \(\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2\) across various genomic annotations were obtained using a larger number of GRMs as described below. SNP-based heritability estimates of binary traits were converted on the liability by multiplying them by \(K(1-K)/[\phi (\varPhi ^-1(K))^2]\), where K denotes the prevalence of the binary trait in the population (here the entire sample of 452,618 European ancestry participants in the UKB), ϕ and Φ−1 are the probability density function and quantile function of a standard normal distribution, respectively.

Pedigree-based estimates

Pedigree-based estimates of narrow sense heritability \((\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2)\) were obtained from a set of 171,446 pairs of relatives (GRM value greater than 0.05) identified in the UKB. For all traits except height, educational attainment and fluid intelligence score, we modelled the phenotypic covariance between relatives (conditionally on a set of covariates X) using the following model:

$$\rmc\rmo\rmv(\,y_i,\,y_j|X)=\sigma _\rmA^2\pi _ij+\sigma _\rmN\rmA^2\pi _ij^2+\delta _ij\sigma _\rmE^2,$$

(3)

where yi and yj are the phenotypes of individuals i and j, πij their observed GRM value and δij a direct indicator variable that equals 1 when i = j and 0 otherwise. Parameters \(\sigma _\rmA^2\), \(\sigma _\rmNA^2\) and \(\sigma _\rmE^2\) capture additive genetic effects, non-additive genetic effects (including effects of shared environments that are correlated with πij) and residual effects, respectively. We estimated these parameters using a computationally efficient maximum-likelihood procedure implemented in R (‘Code availability’). We then used resulting estimates to calculate \(\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2\) as \(\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2=\hat\sigma _\rmA^2/(\hat\sigma _\rmE^2+\hat\sigma _\rmA^2+\hat\sigma _\rmN\rmA^2)\).

For height, educational attainment and fluid intelligence, which are known to be subject to assortative mating (AM), we used a similar model to ref. 50, that is

$$\beginarrayl\rmc\rmo\rmv(\,y_i,\,y_j|X)=\sigma _\rmA^2(0.5)^d_ij[1+\theta ]^d_ij+\sigma _\rmE^2\delta _ij\\ \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\approx \,\sigma _\rmA^2(0.5)^d_ij+\sigma _\rmA^2\theta [(0.5)^d_ijd_ij]+\sigma _\rmE^2\delta _ij\\ \,\,\,\,\,\,\,=\,\sigma _\rmA^2\pi _ij+\sigma _\rmA\rmM^2\pi _ij\left(\frac\rml\rmo\rmg(\pi _ij)\rml\rmo\rmg(0.5)\right)+\sigma _\rmE^2\delta _ij\endarray$$

(4)

where \(d_ij=\log (\pi _ij)/\log (0.5)\) measures the degree of relatedness between pairs of individuals, θ denotes the correlation between genetic values of mates in a population undergoing assortative mating for many generations, and \(\sigma _\rmAM^2=\sigma _\rmA^2\theta \). The first order approximation in equation (4) assumes that θ ≪ 1.

Using estimates of \(\sigma _\rmA^2\) and \(\sigma _\rmE^2\), we then calculated \(\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2\) as \(\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2\,=\,\) \(\hat\sigma _\rmA^2/(\hat\sigma _\rmE^2+\hat\sigma _\rmA^2)\). Note that \(\sigma _\rmAM^2\) does not affect the phenotypic variance because its contribution is multiplied \(\log (\pi _ii)\approx 0\) (in outbred populations). Standard errors for both models (equations (3) and (4)) were obtained using the delta method. We used the TetraHer module51 implemented in the LDAK software tool52 to estimate the heritability of binary traits (under models defined by equations (3) and (4)) directly on the liability scale using the prevalence in the entire sample of European ancestry participants. All analyses were adjusted for the same set of covariates used for GREML analyses.

For each trait, we calculated the EHR as \(\rmE\rmH\rmR=\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2/\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2\). Standard errors of EHR were calculated using the delta method assuming the sampling correlation between \(\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2\) and \(\hath_\rmP\rmE\rmD^2\) is zero. This assumption is supported by the fact that pairs of individuals contributing to each estimator are non-overlapping.

Heritability enrichment in coding variants

We partitioned \(\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2\) to assess the relative contribution of coding and non-coding variants to trait heritability. Specifically, we focused on coding variants within loci covered by WES technologies. We identified these WES loci using the Resource field 3803 (based on IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v.1.0 and 100 bp flanking region upstream and downstream of each capture target). In total, 408,096 (that is, 1% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%) variants were included in the WES-covered regions and 40,167,108 variants were not. We used the Nirvana pipeline version 3.22.0 (Code availability section) to predict the functional consequence of each variant. We defined a set of coding and non-coding variants on the basis of different consequence categories (Supplementary Table 2). Each of the eight MAF and/or LD groups of variants was then split into three subgroups defined as coding variants within WES loci (0.71% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%), non-coding variants within WES loci (0.29% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%) and variants outside WES loci (99% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%). We then calculated a GRM for each of the 24 resulting subsets of variants. We ran GREML analyses simultaneously fitting those 24 GRMs and also fitting the full set of covariates. We defined the heritability enrichment in coding variants using the following equation:

$$\hatE(\rmc\rmo\rmd\rmi\rmn\rmg)=\frac\hath_\rmC\rmo\rmd\rmi\rmn\rmg^2/M_\rmC\rmo\rmd\rmi\rmn\rmg\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2/M_\rmW\rmG\rmS$$

(5)

where \(\hath_\rmC\rmo\rmd\rmi\rmn\rmg^2\) is the overall contribution to \(\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2\) from coding variants and MCoding the total number of coding variants used in the analysis, that is approximately 0.71% of 408,096. Standard errors of \(\hatE(\rmc\rmo\rmd\rmi\rmn\rmg)\) were derived using the delta method. We used a similar approach to define and calculate heritability enrichment in other functional annotations (for example, in non-coding variants within WES loci or in variants within loci that are conserved across species). These further analyses are described in the Supplementary Note 1.

GWAS analyses

We performed associations analyses between 34 phenotypes and WGS variants using Regenie53 while fitting all covariates used for heritability estimation (including 100 k-means for birth coordinates). We computed the step 1 leave-one-chromosome-out genomic predictors using 500,999 LD-pruned common variants (LD r2 > 0.9, window size 10 Mb, MAF > 0.05). We then used these predictors for step 2 in both WGS and imputed datasets. We used a stringent P value threshold of 5 × 10−9 to determine genome-wide significance. We used PLINK54 to clump genome-wide significant associations for each trait into independent loci. The PLINK parameters used to perform clumping were an LD r2 < 0.01 between lead SNPs located within 1 Mb of each other.

To further ensure the statistical independence of our associations, we performed a joint analysis fitting all clumped SNPs simultaneously, then only retained genome-wide significant SNPs from the joint analysis. Joint analyses were performed independently for each chromosome while fitting the same covariates as in marginal GWAS analyses and corresponding leave-one-chromosome-out genomic predictors to account for stratification and cryptic relatedness as implemented in Regenie. Joint analyses used multivariate linear regression for quantitative traits and Firth’s penalized logistic regression for binary traits. Specifically, we used the R package logistf (‘Code availability’) to perform Firth’s correction following the procedure described in ref. 53.

We quantified the proportion of variance explained (on the observed scale) by different sets of associations using the following equation:

$$\hath_\rmG\rmW\rmA\rmS^2=\mathop\sum \limits_j=1^m2p_j(1-p_j)\hat\beta _jm\hat\beta _jc$$

(6)

where m is the number of SNPs in the focal set of association, \(\hat\beta _jm\) and \(\hat\beta _jc\) the (winner’s curse corrected30,31) estimated marginal and conditional effect size of SNP j, respectively. For binary traits, we calculated \(\hath_\rmG\rmW\rmA\rmS^2\) as the proportion of liability variance explained by trait-associated variants using the R code provided in ref. 55 (‘Code availability’) with winner’s curse corrected effect sizes (on the observed scale), and allele frequencies and prevalence from the entire sample set. We calculated \(\hath_\rmG\rmW\rmA\rmS^2\) for CVA and RVAs separately then compared these quantities with their corresponding components of \(\hath_\rmW\rmG\rmS^2\) (Fig. 3a). We re-assessed \(\hath_\rmG\rmW\rmA\rmS^2\) for LDL, HDL and ALK in an independent sample of European ancestry participants of the AGD cohort as described in Supplementary Note 2.

We annotated GWAS-identified variants using Gencode v.39 (ref. 56) to determine their position relative to genes and IDT xGen Exome Research Panel (described above) to assess whether a variant lies within a WES locus. We binned trait-associated variants as a function of their distance to the nearest gene. For annotations, we annotated variants using different methods with respect to their functional role. We used unified rank scores annotations provided by dbSNFP57,58 to evaluate the association of rare variants effect sizes with their predicted pathogenic effects. We selected the main annotations (AlphaMissense59, CADD60, Polyphen2 (ref. 61), Revel62, SIFT63) as well PrimateAI3D36, SpliceAI64 and PromoterAI65. We selected a 0.1 and |0.1| thresholds to define pathogenicity in SpliceAI and PromoterAI, respectively. For all other annotations, we used their normalized percentile score and defined pathogenicity as scores above the third quintile of each standardized scores distribution (Supplementary Fig. 6). Conserved variants were defined as variants with Zoonomia phylogenetic score above 2.27, as done previously34.

Finally, we used SuSiE66,67 to fine-map GWAS loci into 95% credible sets. Loci were defined as genomic regions within a 250-kb window on each side of an independent associations. Effect sizes of binary traits were converted to the liability scale using the method in ref. 55.

GWAS of imputed SNPs from HRC + UK10K and TOPMed panels

We ran similar GWAS analyses (to those described above) simply replacing WGS variants with imputed variants from different panels: the HRC + UK10K imputation panel and the TOPMed imputation panels. We applied similar quality control thresholds to both datasets (MAF > 0.01%, hardcalls genotyping missingness rate less than 0.1, sample missingness <0.05, imputation quality INFO score greater than 0.3 and Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium test P > 10−8). We processed the HRC + UK10K-imputed data locally, while TOPMed-imputed genotypes were processed on the DNA Nexus platform. After the quality control process, we were left with 35,152,666 variants for HRC + UK10K imputation and 35,657,593 for TOPMed imputation. For each dataset, we ran Regenie on dosage genotypes for each of the 34 quantitative and binary phenotypes. We used the leave-one-chromosome-out predictions derived from the step 1 computed on WGS data. We used the same clumping and joint analysis parameters described above to identify independent loci. A fine-mapping analysis with SuSiE (as described above) was also performed for each imputed dataset with similar parameters.

Association between variant density and structural variants

For each CVA, we calculated the density of other CVAs (associated with the same trait) within a window of 100 kb. We hereafter refer this quantity as the CVA–CVA density. We perform the same calculations for RVAs and similarly defined an RVA–RVA density for each RVA. Next, we then assigned each of the GWAS variants to an LD block on the basis of European ancestry-specific GRCh38 LD definitions68. We then used publicly available independent associations for tandem repeats (VNTR) and copy-number variants (CNV) and matched them with the traits in our study (20 out of 34 traits, 8,839 unique variants, 9,542 in total). We used ref. 69 for VNTRs, ref. 70 for array-called CNVs (CNVARRAY) and ref. 71 for WES-called CNVs (CNVWES) to inform of the presence or absence of VNTR, CNVARRAY and CNVWES in proximity of a trait-matched GWAS significant variant. We had 3,397 GWAS variants (3,049 common and 348 rare) located on the same chromosome as a structural variant associated with the same trait. We found 300 out of these 3,397 located within 100 kb (172 common and 128 rare). Finally, we fitted two logistic regression models (for common and rare variants separately) regressing a binary indicator of the presence of a nearby (within 100 kb) trait-associated structural variant onto a binary indicator of CVA–CVA or RVA–RVA density equal or larger than 2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.