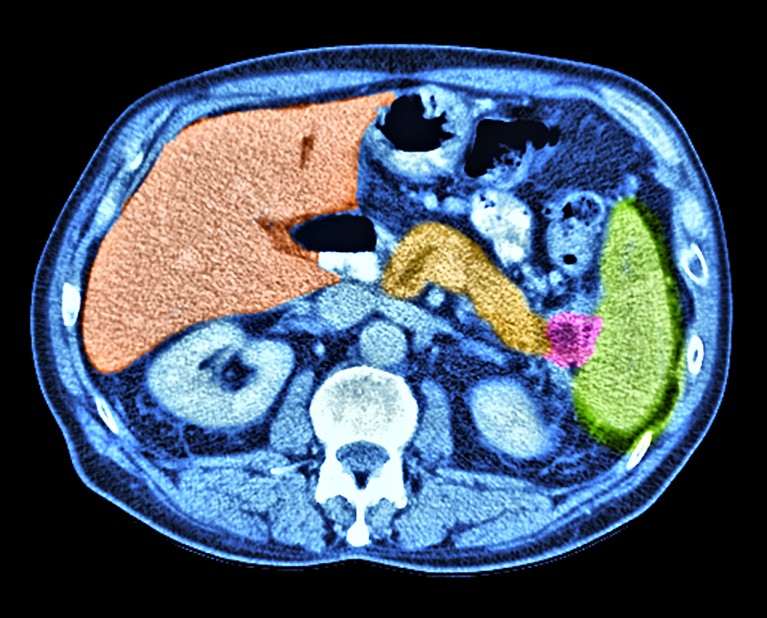

Pancreatic cancer is not a disease that reveals itself easily, at least not initially. The pancreas is tucked deep in the abdomen, behind the stomach, so tumours aren’t easy to see or feel. A person might experience gastrointestinal distress, nausea, back pain, weight loss or fatigue — all symptoms that can be caused by a variety of conditions, most of which are much more common than pancreatic cancer.

By the time an individual develops symptoms that are worrisome enough to prompt a visit to a physician, such as dark urine or pale stools, the cancer has often spread. In four out of five people diagnosed with the disease, the cancer has spread beyond the pancreas and surgery is no longer an option. Once the disease has metastasized, it is almost always deadly. The five-year survival for people with stage four pancreatic cancer is just 3%.

Nature Outlook: Pancreatic cancer

Catching pancreatic cancer early is paramount — and can save lives. In one study1, individuals at high risk of developing the cancer received yearly computed tomography (CT) imaging, endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to look for the disease. Over 23 years, 26 of around 1,700 people in the cohort that underwent surveillance developed pancreatic cancer. Compared with about 1,500 people in a cancer database, those in the surveillance group were more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage and have smaller tumours — 39% had stage one cancer, compared with just 10% in the control group. At the earliest stages, pancreatic cancer can be surgically removed, improving outcomes. The five-year-survival rate was also much higher for the group that underwent yearly surveillance (50% compared with 9% for the control group).

Screening for pancreatic cancer, however, is tricky. Beyond the vague nature of early symptoms, the disease itself is much rarer than many other cancers — the lifetime risk is between 1% and 2%, so screening everyone isn’t feasible. “You can have universal screening for breast cancer and colon cancer,” says Michael Goggins, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. For pancreatic cancer, however, “the numbers don’t add up”, he says. Routine imaging is recommended for some people with an elevated risk, including those with a family history of the disease, with certain genetic variants that make them more susceptible or with some types of pancreatic cyst. But those individuals account for only about 10–15% of pancreatic cancer cases. To catch the other 85% early, researchers first need to find a way to identify more people with a high enough risk of the disease that they would benefit from screening. But even for people with risk factors, identifying the disease is like finding a needle in a haystack. The aim is to bring it down to “a very small haystack before you start looking”, says Suresh Chari, a gastroenterologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

At the same time, researchers need easier ways of detecting pancreatic cancer. The gold-standard imaging tools physicians currently use to spot the disease — MRI and endoscopic ultrasound — are costly and not widely available. So, they are working to identify signatures in the blood called biomarkers that can signal the presence of early-stage cancer.

It’s a daunting problem, and an urgent one. Models suggest that by 2030, pancreatic cancer will become the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, surpassing colorectal cancer, and the third leading cause of cancer deaths in Europe. “We’re trying to give more patients the opportunity for cure,” says Randall Brand, a gastroenterologist at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Shrinking the haystack

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer include old age, obesity, smoking, alcohol and diabetes. But even for people at risk, the disease is rare. People with type 2 diabetes, for example, have about a twofold increased risk, but this still doesn’t amount to many people — certainly not enough to screen the tens of millions of people living with diabetes in the United States. “From an early-detection standpoint, it wasn’t very helpful,” Chari says.

In the 2000s, Chari sifted through the literature and came across something he hadn’t seen before: in some cases, diabetes might be not just a risk factor, but also a symptom of pancreatic cancer. Chari wondered whether he would find more pancreatic tumours in people who were newly diagnosed than in those who had lived with the disease for years.

Pancreatic cancer (pink) can be difficult to identify owing to the position of the pancreas.Credit: Alfred Pasieka/SPL

Two studies from his team – one2 involving more than 2,000 people and a subsequent one3 of nearly 20,000 people — found that, in the three years following a diagnosis of diabetes, adults aged 50 years and older had a much higher risk of pancreatic cancer than did people without diabetes, “six- to eightfold higher than what you expect otherwise”, Chari says. Chari and his team have since used electronic health records to develop an algorithm that attempts to distinguish between regular type 2 diabetes and pancreatic-cancer-associated diabetes4. Those in the latter group tend to be older when diagnosed with diabetes and their blood-sugar levels tend to rise faster in the years before diagnosis. They also tend to lose weight rather than gain it. The model takes into account the individual’s age at diagnosis, and changes in weight and blood glucose levels in the year before diagnosis. It then assigns a pancreatic cancer risk score and stratifies people into three levels of risk, the highest of which contains people who are around 20 times more likely to develop the disease than the general population. “We think that between new-onset diabetes and the impact score, we have defined a high-risk group,” Chari says.

Chari is now testing this model in a trial of nearly 9,000 people. Half of the participants will receive a risk score, and those identified as very high risk will undergo a CT scan. The other half, the control group, won’t receive any pancreatic cancer screening. His team will track pancreatic cancer diagnoses in both groups for five years through electronic medical records. The goal is to assess whether the risk score combined with a scan allows pancreatic cancer to be caught earlier than if people are not screened.

So far, using the model to assess risk through health records has been easy. But participants haven’t had a scan as quickly as Chari would like. The process of getting informed consent has delayed CT scans by three or four months, “which is not what you want to see in real life”, Chari says. The risk is that the delay might mean that they miss the window of opportunity to treat the cancer early and improve survival.

In the United Kingdom, it is recommended that people aged 60 and over, who have new-onset diabetes and have experienced weight loss receive a CT scan within two weeks. To reach even more people who fit these criteria, the UK National Health Service launched a pilot study in June to actively identify individuals at risk by combing through health records at around 300 primary-care facilities.

A blood test would be even easier than a CT scan, and another option for winnowing down he haystack, Chari says. Researchers have yet to identify biomarkers that can reliably detect early-stage pancreatic cancer, but that might soon change.

Hunt for a cancer signal

Since efforts to detect pancreatic cancer early began more than four decades ago, hundreds of potential biomarkers have been tested. But none of them has made it into routine clinical practice. That’s partly because pancreatic cancer is so rare. Any screening tool needs to have an exceptionally high level of accuracy to be useful. “If you apply a marker that’s not perfect in a population that doesn’t have a lot of pancreatic cancer, you’re going to end up working up a lot of false positives,” Brand says.

One of the first biomarkers for pancreatic cancer, identified in 1979, was a protein on the surface of tumour cells called CA 19-9. Although some physicians still use it to track the response to treatment in people with pancreatic cancer, not every individual makes the protein and high levels aren’t always indicative of cancer, limiting its utility.

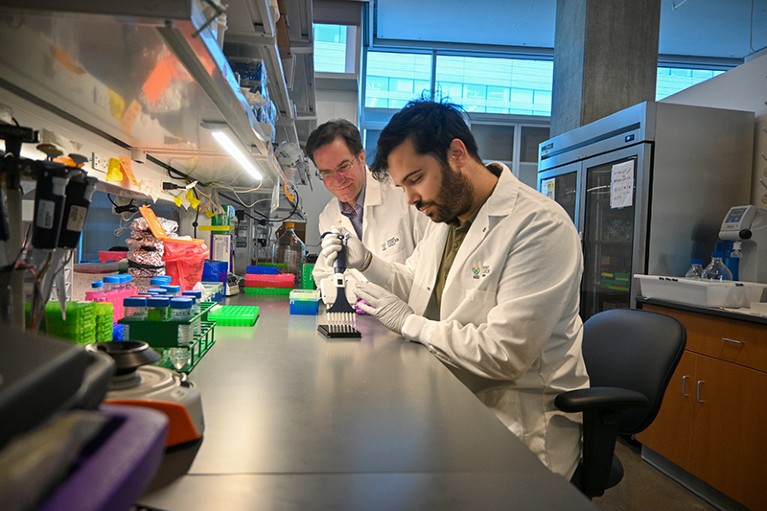

Other proteins seem more promising. Jared Fischer, a molecular biologist at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, and his team have been working on a test that identifies enzymes called proteases, which degrade proteins specific to pancreatic cancer. Proteases occur naturally throughout the body, but in many cancers, including pancreatic cancer, the enzymes help cancer cells to chew up proteins that give tissue structure, such as collagen, clearing the way for cancer to grow, according to Fischer.

His group’s test, called the protease activity-based assay using a magnetic nanosensor, or PAC-MANN, is inexpensive and requires “less than a single finger prick of blood”, Fischer says. He predicts that people will be able to use a home-testing kit to draw a small amount of capillary blood and then send it to a lab for testing. The result could be returned to physicians for them to discuss with the person.

Jared Fischer (left) is working on a test to identify proteases specific to pancreatic cancer.Credit: OHSU/Christine Torres Hicks

The researchers have tested5 their system on blood samples from 356 people. The test performed well, but Fischer says that is often true in small initial studies that use data from the researchers’ own institutions. When the assay is used for a larger number of anonymous samples — the next step for PAC-MANN — performance often “drops like a rock”, he says. He is hoping PAC-MANN will avoid that fate.

Other teams are for looking for signs of pancreatic cancer in strands of RNA. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) help to control the expression of genes, including those that regulate cell growth, division and proliferation. Both normal and tumour cells release miRNAs, and researchers can leverage differences in expression levels of some miRNAs to detect cancer. But they’re not very specific. “You can easily find them, but you’re never certain where they’re coming from,” says Ajay Goel, an oncology researcher at City of Hope, a cancer research and treatment organization based in Duarte, California.

Goel and his colleagues have developed a two-part test that looks not only at miRNA floating in the blood but also at that released inside the tiny-sac-like exosomes that pancreatic and other cells use to offload waste. These exosomes have cell-surface markers that are unique to every tissue type, Goel says, giving researchers a clue as to where they came from. Analysing both types of RNA improves the test’s accuracy by limiting both false positives and false negatives. “That’s exactly what the goal should be for any detection test,” Goel says. In work, presented at the American Association for Cancer Research in 2024, involving about 1,000 people, the test achieved high sensitivity, meaning it managed to accurately identify 97% of people with early-stage pancreatic cancer. The test’s specificity, its ability to accurately identify people who don’t have the disease, was 92%.

Yet another potential biomarker is the snippets of DNA that circulate outside cells. Researchers can collect this cell-free DNA and find signals of cancer in the mutations it carries, the patterns of chemical tags and even the size of the DNA fragments. ClearNote Health, a cancer-detection company in San Diego, California, uses machine learning to predict risk of pancreatic cancer on the basis of the pattern of chemical tags found on cell-free DNA. The test, called Avantect, has a sensitivity of around 68% in detecting early-stage pancreatic cancer — 32% of people who have the disease will get a false-negative result. The test does a better job at ruling out cancer. Only 3% of people who don’t have the disease got an erroneous positive result.

Brand is encouraged by industry finally seeming to take an interest in pancreatic cancer. “It’s really our industry partners that are key to getting it to our patients,” he says. Although many companies are focused on developing multi-cancer detection panels, a few are working on tests that are specific to pancreatic cancer. Both Avantect and PancreaSure, which was developed by Immunovia in Lund, Sweden, are commercially available in the United States. But they aren’t widely used. “Insurance doesn’t pay for them because the level of evidence that’s been generated thus far is not sufficient,” says Anna Berkenblit, chief scientific and medical officer of the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, an advocacy organization in El Segundo, California.

The next test for many of these assays is what’s known as a biomarker bake-off — a competition that allows head-to-head comparisons. So far, the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Bethesda, Maryland, has helped to coordinate two, and a third, which includes PAC-MANN, is under way. During the bake-off, groups of researchers that have developed assays all receive the same samples. Each group runs its test and reports back which samples it has identified as cases of pancreatic cancer and which are not. Results of the second bake-off haven’t yet been published, but “some of the biomarkers seem to be very promising. They are doing better than CA 19-9”, says Sudhir Srivastava, head of the NCI’s cancer biomarkers research group.

Demonstrating that a biomarker can discriminate between cases of cancer and controls is just a first step, says Alison Klein, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Eventually, researchers want to prove that a test can detect cancer before an individual is diagnosed through conventional means. Doing that requires applying the tests to blood samples that were collected months or years before a person was diagnosed, and that’s tricky because “there are not a lot of banks of these samples to test”, says Klein. The hope is that these tests will be sensitive enough to identify cancers that haven’t metastasized and can be removed surgically.

There’s no guarantee that any of these tools will perform well enough to be used for screening, even in high-risk populations. Several tools in combination might be needed, says Berkenblit. But many researchers are optimistic. Klein has seen some promising biomarkers emerge, and efforts to improve imaging by incorporating AI are also in the works. “These are all movement in the right direction,” she says, but “it’s not an easy road”. She understands why families are frustrated with the slow pace of progress.

But because pancreatic cancer is so challenging, that means even small improvements can have a big impact. Klein has been studying pancreatic cancer for decades. “When I started, the survival rate was 5%. Now it’s 13%. That’s a really big difference,” she says. Biomarkers that can catch pancreatic cancer early could boost survival even more. “They have the potential to move the needle.”