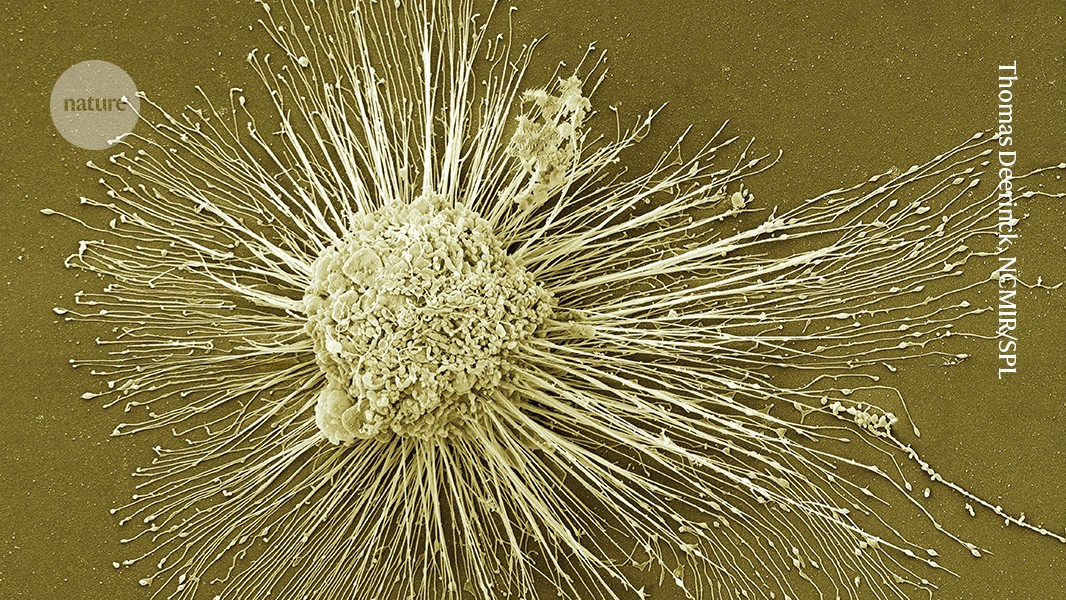

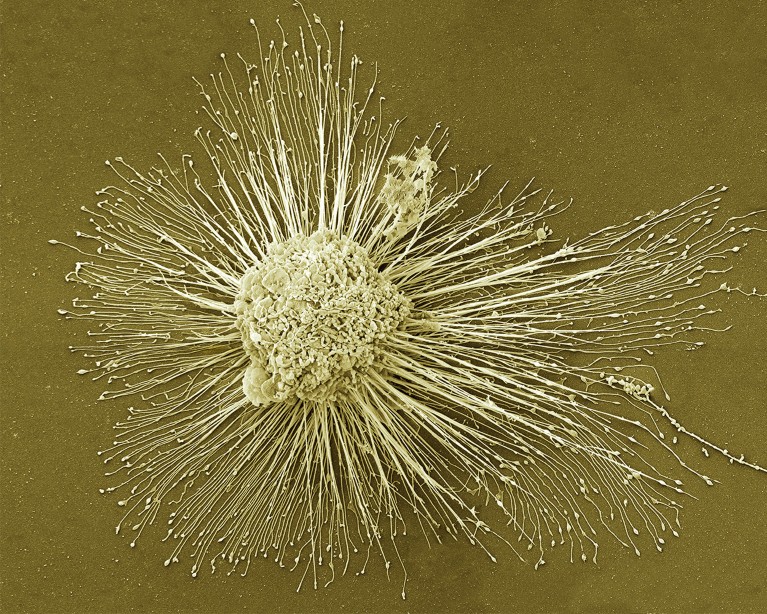

Induced pluripotent stem cells, which can form any of the body’s cell types, could be used to regenerate damaged tissues.Credit: Thomas Deerinck, NCMIR/SPL

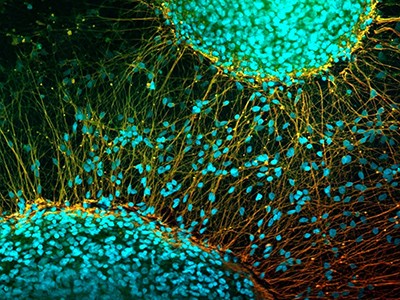

In 2012, the discovery of a way to ‘reprogram’ mature mouse and human cells into a primitive state from which they could develop into any of the body’s cell types won Shinya Yamanaka, a biologist at Kyoto University in Japan, a half share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. His demonstration of how to make these cells, known as induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, also raised hopes that personalized treatments could soon follow, to regenerate damaged tissues such as those of the eye, brain and spine.

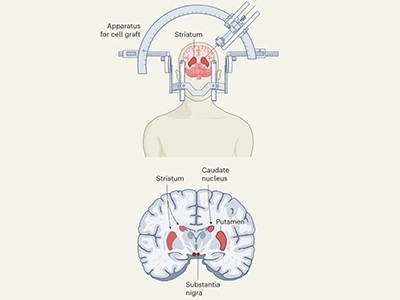

Two studies in Nature this week1,2 report work using stem cells that has clear potential to treat one condition: the progressive neurodegenerative disorder Parkinson’s disease. One research group, based in Japan, injected neural progenitors induced from donor-derived iPS cells into seven individuals. The other team, based in the United States and Canada, injected cells created from embryonic stem cells into 12 individuals.

Clinical trials test the safety of stem-cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease

Both studies, which are reporting the results of early-stage clinical trials, show that the interventions were safe, and that, on average, the recipients experienced measurable improvements in typical symptoms such as tremor and rigid movements.

Although neither study used participants’ own cells, the results nevertheless represent welcome news for a huge number of people. In 2021, some 11.8 million individuals worldwide were living with Parkinson’s3, more than double the number 25 years earlier. The numbers are increasing, and could reach 25 million in the next quarter of a century, according to a modelling study published by The BMJ 4.

Such work has the potential to transform lives, but it is important that these therapies do not move into the clinic too quickly. Researchers must be allowed to take as much time as is necessary to complete safety and efficacy tests.

Many countries are exploring how to get drugs and therapies to market more quickly. Japan is currently in the spotlight, with a slew of its universities, companies and funding bodies preparing to apply for fast-tracked regulatory approval for certain products based on iPS cells, in some cases perhaps even within the year, as we report in a News Feature.

Japan’s big bet on stem-cell therapies might soon pay off with breakthrough therapies

These organizations are working in a system, launched in Japan in 2013, that permits ‘regenerative-medicine products’ to be licensed for temporary use if early-stage clinical trials show that the products are safe to use and have potential for clinical benefit. This system allows products to be rolled out without completing phase III randomized-controlled clinical trials — which are generally considered to be the ‘gold standard’ test around the world. However, after conditional approval, evaluations do continue, and both safety and efficacy must be shown conclusively or the product is withdrawn.

Although clearly riskier than the usual process, in theory, this system allows potentially life-changing interventions to be provided more quickly to people for whom alternative treatments aren’t available. This is one of the reasons why it is being watched closely around the world. The other reason is that there is a perception in many countries that conventional regulation is holding back innovation. Yet early examples from the fast-track process suggest that speed must be tempered with care.

Between 2015 and 2021, two cell-based regenerative-medicine products and two gene therapies were granted conditional approval in Japan under the same system. Safety does not seem to have been an issue, but two of the products did not meet the efficacy requirements for full approval and were withdrawn from the market last year. The performance of the other two is not yet known. They will need to meet the full efficacy requirements in the next few years if they are not to be withdrawn5.

Paralysed man stands again after receiving ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells

One interpretation of this outcome is that the fast-track system’s safeguards are working. But at least two of the candidate treatments clearly needed more time in clinical trials. The failure to achieve the desired level of efficacy meant that patients experienced false hope, and, because treatments granted conditional approval are paid for through Japan’s public health-insurance system, taxpayers were landed with an unnecessary bill.

The fast-track system also incentivizes companies to roll out as many interventions as possible before a product’s conditional approval expires, maximizing potential revenue. This has led some to call for the efficacy requirements for conditional approval to be raised.

The two studies published this week offer hope for people with a disease that is currently only manageable; there is no cure. Such early-phase clinical trials are a crucial part of both the research and the regulatory journey. However, subsequent trials are also essential, because they are designed specifically to assess whether a therapy could benefit patients.

There is a need to raise awareness among both policymakers and the public of why careful and thorough evaluation of new science-based medical products is best for all concerned — patients, researchers and organizations taking such interventions to the clinic. Regenerative medicine is an exciting and promising science, and it has taken researchers decades to bring it to the point of clinical application. Regulators around the world must not put that promise at risk by rushing the final stage of the process.