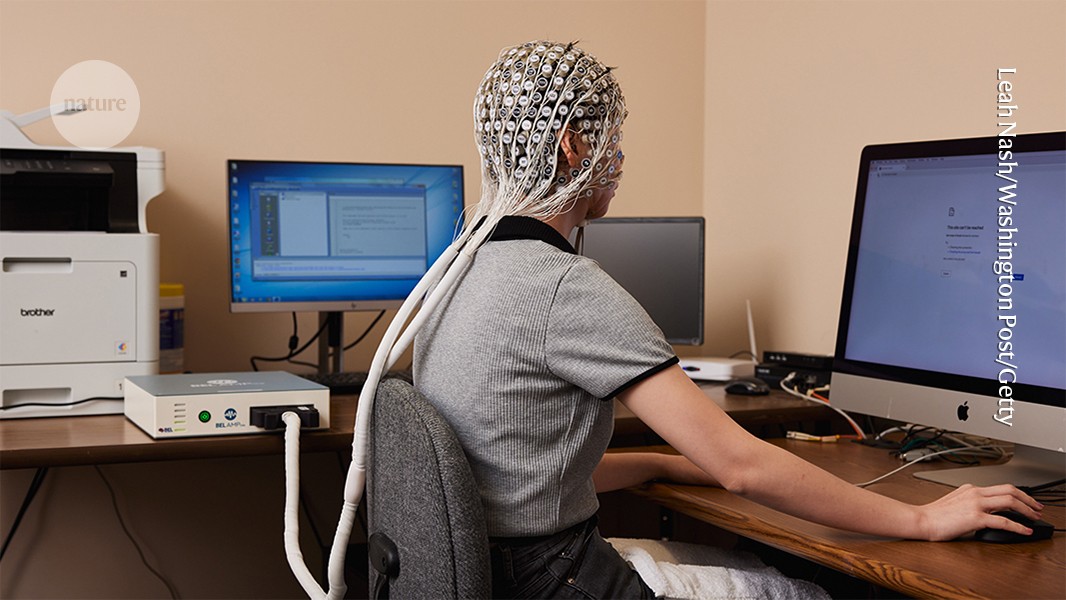

Electroencephalography can be used to study brain activity while people are completing tasks with and without the help of chatbots such as ChatGPT.Credit: Leah Nash/Washington Post/Getty

The brains of people writing an essay with ChatGPT are less engaged than those of people blocked from using any online tools for the task, a study finds1. The investigation is part of a broader movement to assess whether artificial intelligence (AI) is making us cognitively lazy.

How close is AI to human-level intelligence?

Computer scientist Nataliya Kosmyna of the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and colleagues measured brain-wave activity in university students as they wrote essays either using a chatbot or an Internet search tool, or without any Internet at all. Although the main result is unsurprising, some of the study’s findings are more intriguing: for instance, the team saw hints that relying on a chatbot for initial tasks might lead to relatively low levels of brain engagement even when the tool is later taken away.

Echoing some posts about the study on online platforms, Kosmyna is careful to say that the results shouldn’t be overinterpreted. This study cannot and did not show “dumbness in the brain, no stupidity, no brain on vacation”, Kosmyna laughs. It only involved a few dozen participants over a short time period and cannot speak to whether habitual chatbot use reshapes our thinking in the long-term, or how the brain might respond during other AI-assisted tasks. “We don’t have any of these answers in this paper,” Kosmyna says. The work was posted ahead of peer review on the preprint server arXiv on 10 June1.

Easy essays

Kosmyna’s team recruited 60 students, aged 18 to 39, from 5 universities around the city of Boston, Massachusetts. The researchers asked them to spend 20 minutes crafting a short essay answering questions such as “should we always think before we speak?” that appear on Scholastic Assessment Tests, or SATs.

Are the Internet and AI affecting our memory? What the science says

The participants were divided into three groups: one used ChatGPT, powered by OpenAI’s large language model GPT-4o, as the sole source of information for their essays; another used Google to search for material (without any AI-assisted answers); and the third was forbidden to go online at all. In the end, 54 participants wrote three different essays while in their assigned group, and then 18 were re-assigned to a new group to write a fourth essay on one of the topics that they had tackled previously.

Each student wore a commercial electrode-covered cap, which collected electroencephalography (EEG) readings as they wrote. These headsets measure tiny voltage changes from brain activity and can show which broad regions of the brain are ‘talking’ to each other.

The students who wrote essays using only their brains showed the strongest, widest-ranging connectivity among brain regions, and had more activity going from the back of their brains to the front, decision-making area. They were also, unsurprisingly, better able to quote from their own essays when questioned by the researchers afterwards.

The Google group, by comparison, had stronger activations in areas known to be involved with visual processing and memory. And the chatbot group displayed the least brain connectivity during the task.

More brain connectivity isn’t necessarily good or bad, Kosmyna says. In general, more brain activity might be a sign that someone is engaging more deeply with a task, or it might be a sign of inefficiency in thinking, or that the person is overwhelmed by ‘cognitive overload’.