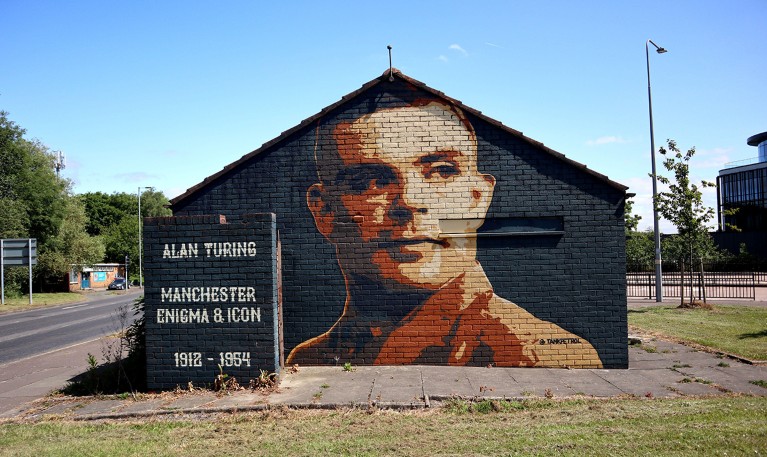

In 1950, in a paper entitled ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’1, Alan Turing proposed his ‘imitation game’. Now known as the Turing test, it addressed a question that seemed purely hypothetical: could machines display the kind of flexible, general cognitive competence that is characteristic of human thought, such that they could pass themselves off as humans to unaware humans?

Three-quarters of a century later, the answer looks like ‘yes’. In March 2025, the large language model (LLM) GPT-4.5, developed by OpenAI in San Francisco, California, was judged by humans in a Turing test to be human 73% of the time — more often than actual humans were2. Moreover, readers even preferred literary texts generated by LLMs over those written by human experts3.

This is far from all. LLMs have achieved gold-medal performance at the International Mathematical Olympiad, collaborated with leading mathematicians to prove theorems4, generated scientific hypotheses that have been validated in experiments5, solved problems from PhD exams, assisted professional programmers in writing code, composed poetry and much more — including chatting 24/7 with hundreds of millions of people around the world. In other words, LLMs have shown many signs of the sort of broad, flexible cognitive competence that was Turing’s focus — what we now call ‘general intelligence’, although Turing did not use the term.

What is the future of intelligence? The answer could lie in the story of its evolution

Yet many experts baulk at saying that current AI models display artificial general intelligence (AGI) — and some doubt that they ever will. A March 2025 survey by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence in Washington DC found that 76% of leading researchers thought that scaling up current AI approaches would be ‘unlikely’ or ‘very unlikely’ to yield AGI (see go.nature.com/4smn16b).

What explains this disconnect? We suggest that the problem is part conceptual, because definitions of AGI are ambiguous and inconsistent; part emotional, because AGI raises fear of displacement and disruption; and part practical, as the term is entangled with commercial interests that can distort assessments. Precisely because AGI dominates public discourse, it is worth engaging with the concept in a more detached way: as a question about intelligence, rather than a pressing concern about social upheaval or an ever-postponed milestone in a business contract.

In writing this Comment, we approached this question from different perspectives — philosophy, machine learning, linguistics and cognitive science — and reached a consensus after extensive discussion. In what follows, we set out why we think that, once you clear away certain confusions, and strive to make fair comparisons and avoid anthropocentric biases, the conclusion is straightforward: by reasonable standards, including Turing’s own, we have artificial systems that are generally intelligent. The long-standing problem of creating AGI has been solved. Recognizing this fact matters — for policy, for risk and for understanding the nature of mind and even the world itself.

Questions of definition

We assume, as we think Turing would have done, that humans have general intelligence. Some think that general intelligence does not exist at all, even in humans. Although this view is coherent and philosophically interesting, we set it aside here as being too disconnected from most AI discourse. But having made this assumption, how should we characterize general intelligence?

A common informal definition of general intelligence, and the starting point of our discussions, is a system that can do almost all cognitive tasks that a human can do6,7. What tasks should be on that list engenders a lot of debate, but the phrase ‘a human’ also conceals a crucial ambiguity. Does it mean a top human expert for each task? Then no individual qualifies — Marie Curie won Nobel prizes in chemistry and physics but was not an expert in number theory. Does it mean a composite human with competence across the board? This, too, seems a high bar — Albert Einstein revolutionized physics, but he couldn’t speak Mandarin.

How close is AI to human-level intelligence?

A definition that excludes essentially all humans is not a definition of general intelligence; it is about something else, perhaps ideal expertise or collective intelligence. Rather, general intelligence is about having sufficient breadth and depth of cognitive abilities, with ‘sufficient’ anchored by paradigm cases. Breadth means abilities across multiple domains — mathematics, language, science, practical reasoning, creative tasks — in contrast to ‘narrow’ intelligences, such as a calculator or a chess-playing program. Depth means strong performance within those domains, not merely superficial engagement.

Human general intelligence admits degrees and variation. Children, average adults and an acknowledged genius such as Einstein all have general intelligence of varying level and profile. Individual humans excel or fall short in different domains. The same flexibility should apply to artificial systems: we should ask whether they have the core cognitive abilities at levels comparable to human-level general intelligence.

Rather than stipulating a definition, we draw on both actual and hypothetical cases of general intelligence — from Einstein to aliens to oracles — to triangulate the contours of the concept and refine it more systematically. Our conclusion: insofar as individual humans have general intelligence, current LLMs do, too.

What general intelligence isn’t

We can start by identifying four features that are not required for general intelligence.

Perfection. We don’t expect a physicist to match Einstein’s insights, or a biologist to replicate Charles Darwin’s breakthroughs. Few, if any, humans have perfect depth even within specialist areas of competence. Human general intelligence does not require perfection; neither should AGI.

Universality. No individual human can do every cognitive task, and other species have abilities that exceed our own: an octopus can control its eight arms independently; many insects can see parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that are invisible to humans. General intelligence does not require universal mastery of these skills; an AGI does not need perfect breadth.

Human similarity. Intelligence is a functional property that can be realized in different substrates — a point Turing embraced in 1950 by setting aside human biology1. Systems demonstrating general intelligence need not replicate human cognitive architecture or understand human cultural references. We would not demand these things of intelligent aliens; the same applies to machines.

Superintelligence. This is generally used to indicate any system that greatly exceeds the cognitive performance of humans in almost all areas. Superintelligence and AGI are often conflated, particularly in business contexts, in which ‘superintelligence’ often signals economic disruption. No human meets this standard; it should not be a requirement for AGI, either.

A cascade of evidence

What, then, is general intelligence? There is no ‘bright line’ test for its presence — any exact threshold is inevitably arbitrary. This might frustrate those who want exact criteria, but the vagueness is a feature, not a bug. Concepts such as ‘life’ and ‘health’ resist sharp definition yet remain useful; we recognize paradigm cases without needing exact boundaries. Humans are paradigm examples of general intelligence; a pocket calculator lacks it, despite superhuman ability at calculations.

When we assess general intelligence or ability in other humans, we do not attempt to peer inside their heads to verify understanding — we infer it from behaviour, conversation and problem-solving. No single test is definitive, but evidence accumulates. The same applies to artificial systems.

Just as we assess human general intelligence through progressively demanding tests, from basic literacy to PhD examinations, we can consider a cascade of increasingly demanding evidence that warrants progressively higher confidence in the presence of AGI.

Turing-test level. Markers comparable to a basic school education: passing standard school exams, holding adequate conversations and performing simple reasoning. A decade ago, meeting these might have been widely accepted as sufficiently strong evidence for AGI.

Current AIs are more broadly capable than the science-fiction supercomputer HAL 9000 was.Credit: Hethers/Shutterstock

Expert level. Here, the demands escalate: gold-medal performance at international competitions, solving problems on PhD exams across multiple fields, writing and debugging complex code, fluency in dozens of languages, useful frontier research assistance as well as competent creative and practical problem-solving, from essay writing to trip planning. These achievements exceed many depictions of AGI in science fiction. The sentient supercomputer HAL 9000, from director Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, exhibited less breadth than current LLMs do. And current LLMs even exceed what we demand of humans: we credit individual people with general intelligence on the basis of much weaker evidence.

Superhuman level. Revolutionary scientific discoveries and consistent superiority over leading human experts across a range of domains. Such evidence would surely allow no reasonable debate about the presence of general intelligence in a machine — but it is not required evidence for its presence, because no human shows this.

Turing’s vision realized

Current LLMs already cover the first two levels. As LLMs tackle progressively more difficult problems, alternative explanations for their capabilities — for instance, that they are gigantic ‘lookup tables’8 that retrieve pre-computed answers or ‘stochastic parrots’9 that regurgitate shallow regularities without grasping meaning or structure — become increasingly disconfirmed.

Often, however, such claims just reappear with different predictions. Hypotheses that retreat before each new success, always predicting failure just beyond current achievements, are not compelling scientific theories, but a dogmatic commitment to perpetual scepticism.

AI language models killed the Turing test: do we even need a replacement?

We think the current evidence is clear. By inference to the best explanation — the same reasoning we use in attributing general intelligence to other people — we are observing AGI of a high degree. Machines such as those envisioned by Turing have arrived. Similar arguments have been made before10 (see also go.nature.com/49p6voq), and have engendered controversy and push-back. Our argument benefits from substantial advances and extra time. As of early 2026, the case for AGI is considerably more clear-cut.

We now examine ten common objections to the idea that current LLMs display general intelligence. Several of them echo objections that Turing himself considered in 1950. Each, we suggest, either conflates general intelligence with non-essential aspects of intelligence or applies standards that individual humans fail to meet.

They’re just parrots. The stochastic parrot objection says that LLMs merely interpolate training data. They can only recombine patterns they’ve encountered, so they must fail on genuinely new problems, or ‘out-of-distribution generalization’. This echoes ‘Lady Lovelace’s Objection’, inspired by Ada Lovelace’s 1843 remark and formulated by Turing as the claim that machines can “never do anything really new”1. Early LLMs certainly made mistakes on problems requiring reasoning and generalization beyond surface patterns in training data. But current LLMs can solve new, unpublished maths problems, perform near-optimal in-context statistical inference on scientific data11 and exhibit cross-domain transfer, in that training on code improves general reasoning across non-coding domains12. If critics demand revolutionary discoveries such as Einstein’s relativity, they are setting the bar too high, because very few humans make such discoveries either. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that human intelligence is not itself a sophisticated version of a stochastic parrot. All intelligence, human or artificial, must extract structure from correlational data; the question is how deep the extraction goes.

They lack world models. LLMs supposedly lack representations of their physical environment that are necessary for genuine understanding. But having a world model requires only the ability to predict what would happen if circumstances differed — to answer counterfactual questions. Ask a cutting-edge LLM what differs between dropping a glass or a pillow on a tile floor, and it will correctly predict shattering in one case and not the other. The ability of LLMs to solve olympiad mathematics and physics problems and assist with engineering design suggests that they possess functional models of physical principles. By these standards, LLMs already have world models. Furthermore, neural networks developed for specialized domains such as autonomous driving are already learning predictive models of physical scenes that support counterfactual reasoning and sophisticated physical awareness13.

Alan Turing asked whether machines could think. Credit: Gerard Noonan/Alamy

They understand only words. This objection centres on the fact that LLMs are trained only on text, and so must be fundamentally limited to text-based tasks. Frontier models are now trained on images and other multimodal data, making this objection somewhat obsolete. Moreover, language is humanity’s most powerful tool for compressing and capturing knowledge about reality. LLMs can extract this compressed knowledge and apply it to distinctly non-linguistic tasks: helping researchers to design experiments — for example, suggesting what to test next in biology and materials science4 — goes beyond merely linguistic performance. We are yet to encounter the sharp limitations to LLM performance that this objection predicts.

They don’t have bodies. Without embodiment, critics argue, there can be no general intelligence. This reflects an anthropocentric bias that seems to be wielded only against AI. People would ascribe intelligence to a disembodied alien communicating by radio, or to a brain sustained in a vat. An entity that responds accurately to any question, but never moves or acts physically, would be regarded as profoundly intelligent. Physicist Stephen Hawking interacted with the world almost entirely through text and synthesized speech, yet his physical limitations in no way diminished his intelligence. Motor capabilities are separable from general intelligence.

They lack agency. It is true that present-day LLMs do not form independent goals or initiate action unprompted, as humans do. Even ‘agentic’ AI systems — such as frontier coding agents — typically act only when a user triggers a task, even if they can then automatically draft features and fix bugs. But intelligence does not require autonomy. Like the Oracle of Delphi — understood as a system that produces accurate answers only when queried — current LLMs need not initiate goals to count as intelligent. Humans typically have both general intelligence and autonomy, but we should not thereby conclude that one requires the other. Autonomy matters for moral responsibility, but it is not constitutive of intelligence.