The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) plans to cut off funding for certain projects about climate change, greenhouse gases and fossil fuels.

Specifically, the agency is poised to no longer financially support research on why Earth’s climate is changing, on how to enhance climate-change literacy, on assessing climate-change anxiety and more, according to internal NIH documents and e-mails that Nature has obtained.

Trump gutted two landmark environmental reports — can researchers save them?

The documents, which were sent to the top grants officials at 9 of the NIH’s 27 institutes and centres, provide an inside look at how the agency under US President Donald Trump will fund research at the intersection of human health and climate. For those who feared that the administration might cancel all projects mentioning climate change — which Trump has in the past called a “hoax” — the latest directive comes as welcome news.

But others see the NIH’s changing focus as undermining its stated commitment to extending the lifespan of people in the United States. If the goal “is to have Americans as uninformed as possible about the challenges we’re facing, that’s a pretty devastating comment on the administration’s concern for the health of Americans”, says Kristie Ebi, a specialist in climate, weather and human health at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The NIH, which is the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research, did not respond to Nature’s queries about the new guidance, the forthcoming cuts to climate-related grants or scientists’ frustrations. It is unclear whether the documents have been finalized or whether they are subject to further change.

Decisions, decisions

Before 2022, the NIH had been investing about US$10 million per year in research on the human-health impacts of a rapidly warming world — small change for an agency with an annual budget of about $47 billion. But that year, the administration of former US president Joe Biden, Trump’s predecessor, launched the Climate Change and Health Initiative (CCHI), which prioritized environmental-health research and coordinated it across the entire agency. The CCHI received $40 million from the US Congress in both 2023 and 2024.

The initiative’s fate has been in question since Trump took office in January, given that its website has been taken down, and media reports emerged that the agency would end all future research on the health effects of climate change. It now appears that the CCHI is getting rebranded: it will be called, at least internally, the Health and Extreme Weather initiative.

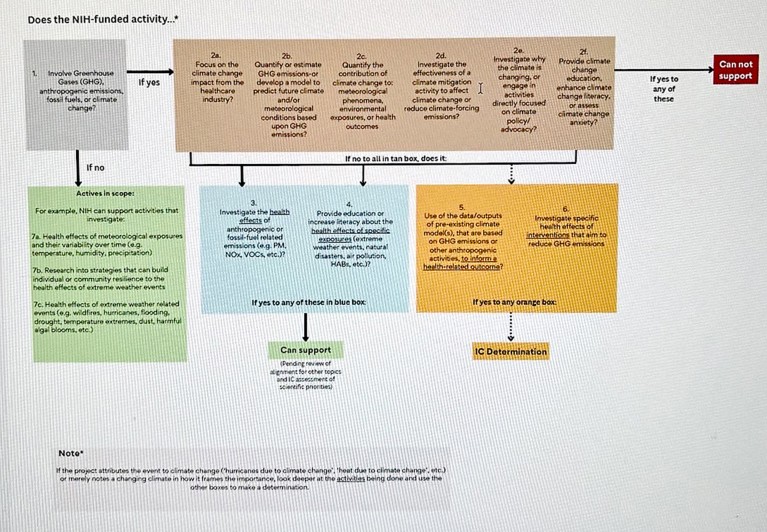

A decision tree circulating amongst NIH staff members that indicates which climate-related grants can still be funded (see Supplemental Info below for PDF).

The research the initiative funds will change too, reflecting a push to focus on extreme-weather events rather than the changing climate or the conditions making those events more likely. Nature obtained a decision tree (see above) that will be used to help grants-management staff to evaluate whether to fund or terminate projects.

Much of the research that the CCHI funded, focused on the health effects of weather-related events such as wildfires or heatwaves, will continue. That comes as a relief to Ebi: “In the short term, it doesn’t matter if a wildfire is attributed to climate change — people need answers to its impacts on health and how to mitigate that risk,” she says.

But a slew of research is no longer deemed within NIH’s remit, the documents show. For example, projects creating educational modules for classrooms on climate change are out. And so is one investigating how to make a more climate-friendly asthma inhaler (inhalers usually release a greenhouse gas when used). “Greenhouse gases are the reason we have climate change, and the problem will get worse unless we address them,” says Preeti Jaggi, an infectious-diseases physician at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, who also studies the sustainability of the healthcare industry.

Joshua Rosenthal, an environmental-health researcher who co-led the CCHI until his retirement in March, says the more that Trump administration officials “narrow the ability of NIH to support research that will protect people from the harms of climate change, the more people will suffer”.