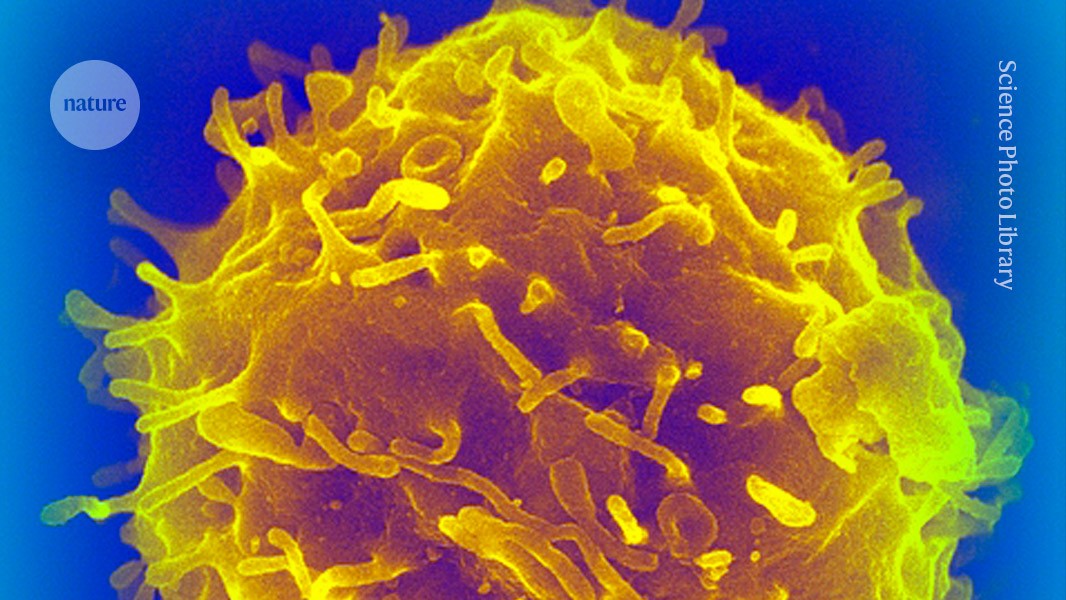

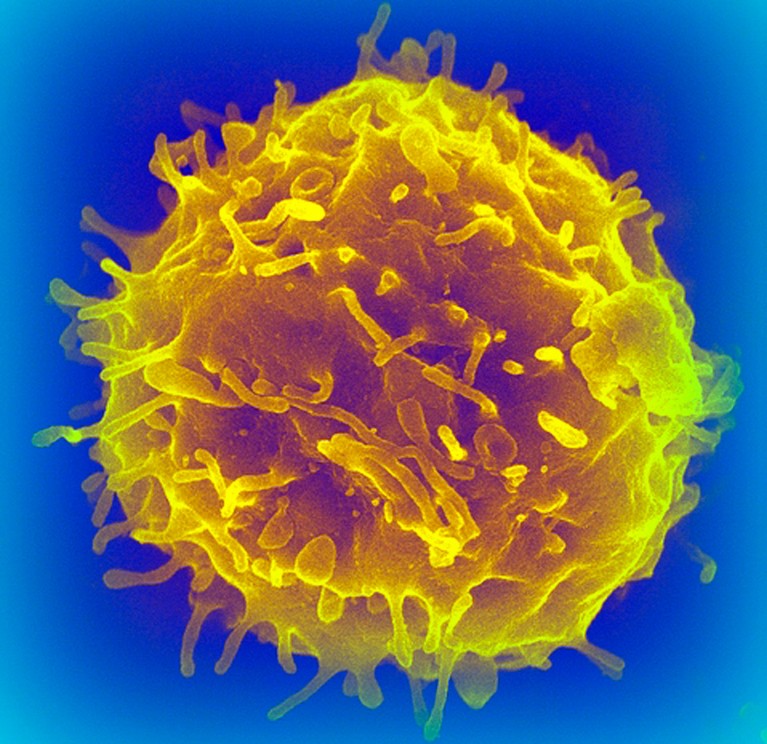

Haematopoietic stem cells from donors have been used to treat hundreds of thousands of people with blood cancer and other blood disorders.Credit: SPL

Ever since the first blood-forming stem cells were successfully transplanted into people with blood cancers more than 50 years ago, researchers have wondered whether they developed cancer-causing mutations. A unique study1 on the longest-lived transplant recipients and their donors has revealed that people who receive donor stem cells don’t seem to have an increased risk of developing such mutations.

The results are surprising but reassuring, says Michael Spencer Chapman, a haematologist at the Barts Cancer Institute in London.

“It’s fantastic news for people undergoing these therapies,” says Alejo Rodriguez-Fraticelli, a quantitative stem-cell biologist at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Barcelona, Spain.

Blood-forming, or ‘haematopoietic’, stem cells are precursor cells that reside in the bone marrow and give rise to all types of blood cell. They have been used to treat hundreds of thousands of people with blood cancers and bone-marrow diseases. The transplants involve depleting a person’s entire blood stem-cell reserves and replacing them with cells from a healthy donor. But researchers have long worried that putting the cells under such pressure could increase the risk of cancer. In rare cases, about 1 in every 1,000 transplants, donor cells develop into a cancer in the recipients.

Fishing expedition

The latest study, published in Science Translational Medicine this week, looked at mutations in specific genes that have been linked to cancer. It was thought that these mutations could give haematopoietic cells a growth advantage in transplant recipients, allowing them to rapidly divide and multiply as the recipient ages and eventually develop into leukaemia.

Some of the first transplants were conducted at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center starting in the late 1960s. In 2017, Masumi Ueda Oshima, a clinical researcher who studies post-transplant ageing at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, and her colleagues decided to reach out to the recipients of these transplants, and their donors, to collect samples of their blood and compare how the cells had aged. “It was really a big fishing expedition,” she says.

The team collected blood samples from 32 individuals — 16 donor–recipient pairs — who had received their transplants between 7 and 46 years ago. They used a highly sensitive technique to sequence genes known to acquire mutations associated with bone-marrow cancers.

The team found cells with mutations in all the healthy donors, even those as young as 12 years old. The older the donor, the mutations were present in their blood, but overall the frequency remained low — just one in a million of the sequenced base pairs.

The researchers then compared mutation patterns in 11 donor–recipient pairs for which they could access donor blood samples from the time of the transplant. They found similar mutation patterns in both groups. On average, mutations occurred at a rate of 2% per year in donors, and 2.6% per year in recipients. “Surprisingly, there actually are very few new mutations in the stem cells arising through the transplant process,” says Spencer Chapman. That suggests transplant recipients’ cells age at a similar rate to those in their donors, and they don’t have an increased risk of developing mutations, which might predispose them to blood cancers.

The fact that the mutations remain stable for so long after a transplant shows that “the regenerative capacity of the hematopoietic system is really profound”, says Ueda Oshima.

Rodriguez-Fraticelli says that although the results are comforting, they are based on a small number of individuals, which makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions.

Complex ageing

Spencer Chapman observed similar results in a separate study of donor–recipient pairs2, which was been posted online as a preprint in April 2023. His study included 10 transplant recipients who received haematopoietic cells from their siblings between 9 and 31 years earlier. But they didn’t just look for changes in specific genes associated with cancer, instead they extracted and grew haematopoietic cells in a dish and sequenced the entire genomes of individual cells. On average, they found that recipients had only slightly more mutations than their donors, adding just 1.5 years of normal ageing — a similar finding to Ueda Oshima’s.

When he and his colleagues looked specifically at mutations known to give cells a growth advantage, they noticed that cells that had only one of these mutations were found at similar levels in recipients and donors. But cells with two or more of these advantageous mutations were present at higher levels in recipients than donors. The result could help to explain why in rare cases, transplanted cells can develop into tumours.

But more work is needed to better understand the implications of these ageing processes, in terms of cancer risk and immune function, says Spencer Chapman.

Both studies could have implications for people receiving stem-cell transplants and blood-based gene therapies to treat sickle-cell disease, for example. More of these therapies are “hitting the mainstream” and being given to children, who will need to rely on the transplanted cells for the rest of their lives, says Spencer Chapman.