There’s a book perched near the top of The New York Times bestseller list about what’s wrong with kids today. The Anxious Generation (2024), by psychologist Jonathan Haidt, argues that increasing time spent on smartphones and social media, at the expense of play, is rewiring the brains of children and adolescents and driving soaring rates of mental illness. It leapt to the top of the bestseller list when it was released a year ago and has sat there ever since.

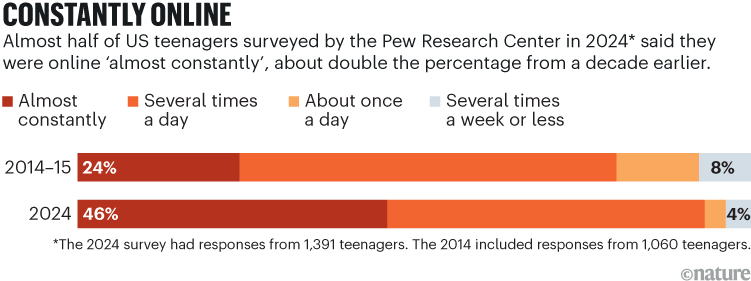

The book reinforced an acute concern among many Western parents about the time that their children spend on smartphones and other screens. In a 2024 survey, nearly half of US teenagers said they were online almost constantly, compared with 24% a decade earlier (see ‘Constantly online’), and one-third used social-media sites such as YouTube almost all the time. Parents are troubled by this technology because “it’s new, it’s different, and it’s not the way that they were raised”, says psychologist Sarah Coyne at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

Although researchers agree that adolescents are struggling with mental health, there is fierce debate about how much phones and social media are to blame. Some scientists say the copious research done so far does not show a large effect of these technologies on teenagers’ psychological health. “Science to date does not support the widespread panic around social media and mental health,” says Candice Odgers, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, who has criticized Haidt’s conclusions.

Source: Pew Research Center

Scientists acknowledge that smartphones and social media can potentially be harmful for some people, if screen time displaces healthy activities, such as sleep, or if posts encourage them to self-harm, for instance. But these tools can also help people connect to support, advice, education and friends. The impact “depends on the individual themselves and their history and their physiology, the content and the context”, says Coyne.

And many researchers are concerned that parents and children are hearing the alarming message propagated by Haidt’s blockbuster book and major media, rather than the more nuanced one suggested by other scientists. Some authorities, meanwhile, are moving to ban phones from schools or restrict teenagers’ access to social media. “Parents and kids are very aware of the narrative and very worried,” says Megan Moreno, an adolescent-medicine physician at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. That sparks family battles over screens — and leaves parents unsure what to do.

Alarming trends

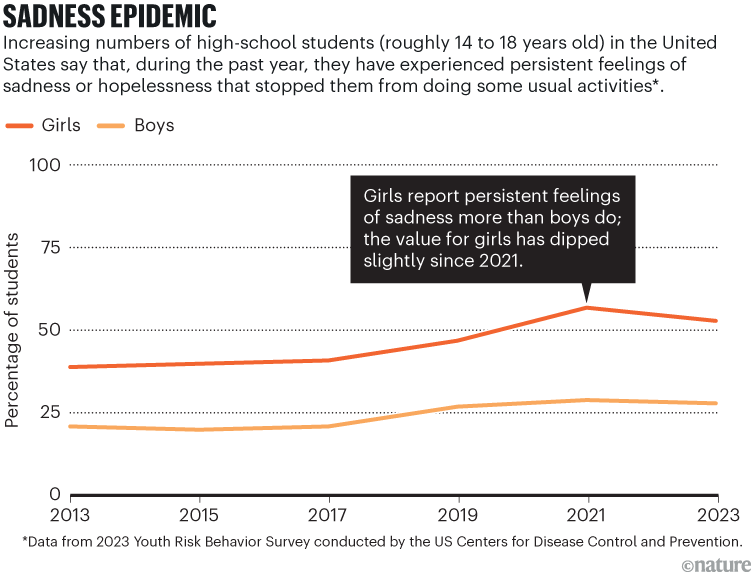

No one denies that adolescent mental health is a huge concern. Research shows that, over the past two decades, rates of mental illness have been increasing in adolescents in many countries1 (see ‘Sadness epidemic’). For instance, surveys of US adolescents found that the share reporting symptoms of depression rose from 16% in 2010 to 21% in 2015 — mostly due to increases in girls — and that rates of suicide rose from 5.4 to 7 per 100,000 in the same period2. Researchers suspect that some of these trends could be down to increased awareness and reporting of mental-health concerns — but they have also searched for other causes.

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Haidt, who works at the New York University Stern School of Business, points out in his book that the upswing in mental illness coincides with the widespread adoption by teenagers of smartphones (the iPhone was launched in 2007) and argues that this edged out real-world socializing, playing and sleep. He then draws on many studies of different types to build an argument that “This Great Rewiring of Childhood … is the single largest reason for the tidal wave of adolescent mental illness that began in the early 2010s”. Haidt points in particular to evidence that heavy social-media use by pre-teen girls is linked to depression and anxiety. “Whenever you look at anxiety, depression, you almost always find the effects are larger,” he told Nature.

But other researchers have criticized some of his views. Odgers published one of the most biting critiques in a review of Haidt’s book (see Nature 628, 29–30; 2024). His argument that digital technologies are driving an epidemic of mental illness “is not supported by science”, she wrote, suggesting that Haidt might be mistaking correlation between technology use and mental illness for causation.

At the heart of the dispute is a large, complex and often conflicting body of research that different researchers interpret in different ways.

Many scientists have looked for correlations between measures of screen or social-media use and mental health in cross-sectional studies — which collect data at one moment in time — or longitudinal studies, which track people over time. Although some studies have found benefits, others have reported harms. A big weakness in such analyses is that they often rely on participants self-reporting the time they spend on screens. This is usually inaccurate, because people can’t remember or are embarrassed to answer honestly. “We all agree it’s terrible,” Haidt says.

Are screens harming teens? What scientists can do to find answers

To try and make sense of the conflicting literature, researchers have done dozens of reviews analysing many studies together, again with varying results. Many have found relatively weak associations and small effects of these technologies on mental health. One 2020 analysis3 of more than 80 reviews concluded that there was, on average, a “negative but very small” association between adolescents’ use of digital technology, and social media in particular, and psychological well-being. A 2024 literature review4 by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine “did not support the conclusion that social media causes changes in adolescent health at the population level”.

It’s also unclear in some studies, say Odgers and some other researchers, which comes first: whether social media causes depression, for instance, or whether young people who are depressed are more likely to spend time on social media. “We might have the arrow pointing in the wrong direction,” Odgers says.

The evidence from experiments in which people swear off smartphones or social media for a spell has also been somewhat equivocal. One systematic review5 of 23 mostly randomized trials found some evidence that abstaining from social media improved measures of depression, says Ruth Plackett, a health researcher at University College London who led the review. But other studies found no effect.

From all this evidence, researchers have arrived at differing conclusions. Odgers and others worry that the focus on phones risks distracting scientists and policymakers from other important, but harder-to-tackle, contributors to adolescent mental-health problems, such as poverty, inequality, violence, discrimination and isolation. “We have young people in crisis, and part of it might be technology,” says Amy Orben, who studies digital mental health at the University of Cambridge, UK. “But we also have other areas that we really, truly know influence mental health that aren’t getting near the time they need.”

Haidt takes a different view. He says that the type of small effects that scientists have found is not unusual in public-health studies based on crude measures, such as self-reported screen time. He argues that the effects are often masked when researchers combine and analyse different results — such as data on boys and girls, or measures of overall well-being with those on depression. The links are clearer, he says, in analyses centred on depression and anxiety. “So this is getting very frustrating, because the evidence of harm is there.”

Divergent data

Many scientists say the impacts of smartphones and social media depend on the individual, their family and other circumstances, and what they are doing online. A 2021 study of nearly 400 adolescents, for example, found that 28% of participants felt worse after using social-media platforms (mostly WhatsApp, Snapchat and Instagram), 26% felt better and 45% felt neither better nor worse6.

Such results might help to explain why some other studies, which look at averages, find little impact, says Ine Beyens, a communications researcher at the University of Amsterdam, who led the study. “When you put all these effects together, of course, in the end, you have a very small effect,” she says.

Some researchers have observed potential benefits for certain groups. Coyne researches under-represented populations, including transgender and non-binary youth, and she says, “they’re using their phones in really effective ways, a lot of the time, to find belonging and community”7.

By contrast, a small proportion of young people do use their smartphones or social media in problematic ways, researchers and physicians say, and there is debate about how to define and diagnose what constitutes pathological use. “Nothing one does for eight or nine hours a day — except for sleep — should be viewed as a healthful activity,” says Dimitri Christakis, a paediatrician and researcher at the Seattle Children’s Research Institute in Washington.

Governments are banning kids from social media: will that protect them from harm?

And for some, social-media use can lead to devastating consequences. In September 2022, for instance, a London coroner’s inquest found that 14-year-old Molly Russell “died from an act of self-harm whilst suffering from depression and the negative effects of on-line content”. The inquest heard that Russell had viewed content about self-harm and suicide on the platforms Instagram and Pinterest before she took her own life in November 2017.

During the inquest, a representative of Meta, which owns Instagram, defended the platform’s policies, and a Pinterest representative admitted that the site was not safe when Russell used it. In response to the inquest findings, both firms pointed to ways they were improving their sites. Last year, Instagram launched ‘teen accounts’, which restrict the content young users can view.

Such cases are horrific and tragic, says Coyne, and lead to understandable fear among parents that something similar could happen to their child. But jumping from anecdotal cases to an assumption that social media is a terrible peril for all teenagers is problematic, she and other scientists say. “That’s a genuine fear,” says Coyne, but the “likelihood of that is really, really small”.