Theory

For a gas mixture, the differential cross-section of Migdal effect from neutron–nucleus scattering in the soft limit is given by26,27,57

$$\frac\rmd^2\sigma \rmdE_\rmR\rmdE_\rme=\sum _i\frac\rmd\sigma _\rms^i\rmdE_\rmR\sum _n\kappa \frac\rmdp_\upsilon ^i(n\kappa \to E_\rme)\rmdE_\rme$$

(2)

where the summation over i accounts for each species in the gas mixture. \(\sigma _\rms^i\) denotes the scattering cross-section, which includes contributions from elastic (n, n), inelastic (n, n′), fission (n, 2n) and radiative capture (n, γ) processes and can be obtained from the ENDF database ENDF/B-VIII.0 (ref. 58). The term \(p_\upsilon ^i(n\kappa \to E_\rme)\) is the transition probability for ionization of an electron from an initial state nκ to a final state with energy Ee. This probability can be obtained from first principles using the Dirac–Hartree–Fock method27,57. As we use a 2.5-MeV D–D neutron beam and require an approximately 50 keV NR threshold in our analysis, the chemical bonds of C–H and C–O (about 10 eV) are easily broken at our recoil energies. Accordingly, it is reasonable to approximately treat the C, H and O as the free atoms in our NR energy regime and calculate the likelihood of electrons from Migdal scattering as the sum of the individual Migdal transition probabilities for C, H and O, respectively. Note that we include all final states with at least one electron above the energy threshold of detector, \(E_\rme^\mathrmth\). This is particularly relevant as it allows for a precise description of the Migdal effect in the experiment.

To compare with the elastic scattering cross-section, we calculate the total Migdal cross-section by integrating over the kinematically allowed range of NR energies and the energy spectrum of emitted electrons in equation (2):

$$\sigma _\textMigdal=\int _\textmax[E_\rmR^\textmin,E_\rmR^\rmth]^E_\rmR^\textmax\int _E_\rme^\rmth^E_\rme^\textmax\frac\rmd\sigma _\rms^i\rmdE_\rmR\sum _n\kappa \frac\rmdp_\upsilon ^i(n\kappa \to E_\rme)\rmdE_\rme\rmdE_\rme\rmdE_\rmR$$

(3)

where \(E_\rmN^\max \) can be expressed as \(E_\rmR,\rmm\rma\rmx=\frac4m_\rmnm_\rmTE_\rmn(m_\rmn+m_\rmT)^2\), where mn is the mass of the incident neutron, mT is the mass of the target nucleus and En is the kinetic energy of incident neutron. \(E_\rme^\max =10\,\mathrmkeV\). \(E_\rmn^\mathrmth\) and \(E_\rme^\mathrmth\) are the thresholds of detector for nucleus and electron recoils, respectively. The ratio \(r=\sigma _\textMigdal/\sigma _\textElastic\) will offer a direct measure to assess the impact of the Migdal effect in dark matter detection experiments. Extended Data Fig. 1e compares the theoretically calculated Migdal differential probabilities for the gas mixture with the experimentally measured results (more detailed information of the theoretical cross-section calculations can be found in Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information Note 1). The integrated theoretical probability in the 5–10 keV range is 3.9 × 10−5, which is consistent with the experimental result of \((4.9_-1.9^+2.6)\times 10^-5\) within the margin of error.

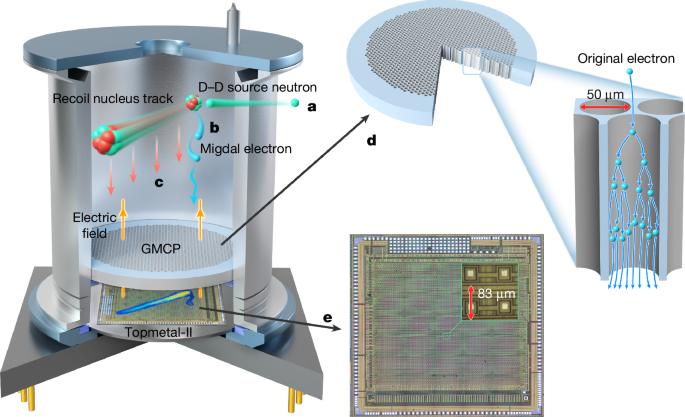

Detector assembly

The detector unit is sealed using brazing and laser welding to ensure high gas tightness and good mechanical properties. The main detector components—ceramics, Kovar alloys, beryllium and lead glass—have a low out-gas rate, which greatly reduces the pollution of other impurities in the gas. To fill the detector with working gas, the detector has a gas pipe that is brazed to the cathode. By using brazing technology, the metal ceramic tube shell is constructed of three layers of ceramic rings and four layers of Kovar alloy rings, with a ceramic ring placed between every two layers of Kovar alloy rings. The ceramic layer is used for insulation and positioning between the Kovar alloy layers. The Kovar alloy rings at both ends of the cermet tube shell are used to seal the connection with the cathode and the base by laser welding. The middle two Kovar alloy rings are used to install the gas microchannel plate (GMCP) as the exit electrode of the GMCP. The GMCP is installed in a cermet tube, and the support ring is extruded to fix the GMCP. The two electrodes of the GMCP are electrically connected by the Kovar alloy on the metal cermet tube. The ceramic pedestal is also composed of ceramic and Kovar alloy. A pixel chip is mounted on the ceramic pedestal and electrically connected to the ceramic pedestal using gold wire. The power supply of the pixel chip and information transmission are realized by 24 pins on the ceramic pedestal. The basic performance of the detector is tested59, the parameters and performance of GMCP are provided60, detailed parameters of the Topmetal-II chip are described52,61 and the electronic information of the detector is given62. The structure of the detector and its geometric parameters are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a.

Electronic system and data acquisition

The electronics system is functionally divided into three layers: (1) the front-end electronics readout board, (2) the back-end electronics board and (3) the high-voltage board. The front-end electronics board primarily includes the gas pixel detector (GPD) unit and the GPD data readout circuit. The back-end electronics board comprises the main controller, data and firmware storage, communication interfaces and devices, and an external clock. The high-voltage board consists of the GMCP bottom-surface feedback circuit, voltage divider circuit, high-voltage chip and monitoring circuit.

Front-end board

It is positioned at the top of the electronics system to host the GPD. The performance metrics of the Topmetal-II can be adjusted by external voltages.

Back-end electronics board

It is responsible for multi-channel signal processing. The FPGA (field-programmable gate array) is equipped with flash memory, storing multiple files to ensure the system can boot correctly in the event of original file corruption. Backup configuration files are stored at specific addresses to mitigate the risk of system startup failures due to FPGA configuration errors.

High-voltage board

It generates and regulates high voltage. The GMCP bottom surface produces pulse signals on electron arrival, which can serve as GPD trigger signals. These signals are processed through a comparator to enhance energy resolution.

Topmetal-II data processing

During detection, the output data from the Topmetal-II is quantized, encoded, compressed and stored in real-time in the embedded Multi-Media Card. The GMCP bottom surface signals, coordinated universal time (UTC), system operational status and monitoring data are stored in the embedded Multi-Media Card with different headers. The scanning frequency of the chip determines the performance metrics of the detector, with pixel switching frequency required to be maintained at the MHz level. Consequently, a data compression scheme has been integrated into the data processing. The detector uses the difference compression method for data compression: the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of each pixel per frame is stored and compared with the ADC value of the previous frame. If the difference exceeds a preset value, the pixel is identified as a signal pixel and transmitted to the erasure module, thereby achieving data volume compression. The frame refresh time of the Topmetal is 2.59 ms, and the coincidence timing resolution between the GMCP signal and the Topmetal is 262 ns (ref. 63).

Detector calibration

The energy resolution of the detector is calibrated with a 5.9-keV 55Fe source. Photons emitted by 55Fe pass through a collimator and then through a beryllium window above the detector, generating photoelectrons and depositing energy in the detector. The energy spectrum is fitted using a Gaussian distribution, and the full width at half maximum of resolution at 5.9 keV is obtained to be 26.54% (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Further tests on the detector demonstrate strong linearity in its energy response, and the variation of energy resolution with energy can be described by a relationship proportional to 1/√E (ref. 64).

The deconvolution method is used to evaluate the position resolution of the detector65. When measuring the position resolution of the detector, the experimental distribution is treated as the convolution of the theoretical distribution with the detector resolution function. In practical terms, a flat and smooth-edged copper plate is positioned directly above the detector. X-rays propagate vertically from the source through both the detector and the copper plate. Consequently, the copper plate obstructs a portion of the X-rays, allowing only half of them to enter the detector. The resulting image obtained by imaging the X-rays with the detector shows only the half irradiated by X-rays. In this scenario, the theoretical distribution can be represented by a Dirac Delta function, whereas the experimental distribution can be expressed as the spatial resolution Gaussian function of the detector. The average σ measured in the X and Y directions is 2.4 pixels (200 μm; Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Simulation

The software framework Star-XP66, specifically developed for this type of gas detectors, is used to simulate Migdal events. Star-XP is built on the well-established GEANT4 simulation platform, which incorporates high-precision neutron collision data from evaluated databases such as ENSDF and JEFF, with rigorous validation for neutron energies below 20 MeV (ref. 67). In particular, it uses the G4NDL4.6 dataset derived from ENDF, ensuring reliable low-energy neutron simulations. The framework considers various primary effects of charged particle motion and ionization in gas, incorporates electronic logic for digitized outputs consistent with experiments and, based on theoretically calculated Migdal electron spectra, integrates a dedicated Migdal effect generator to investigate event selection algorithms and efficiencies.

A comprehensive detector simulation has been implemented in GEANT4, incorporating all main structural components of the experimental setup, including the gas-sensitive detector, ceramic supports, GMCP glass frame, beryllium window and surrounding lead shielding. The model also contains the liquid scintillator system for monitoring neutron flux and spectrum inside the shielding enclosure. This full-scale implementation enables a realistic treatment of particle transport and interactions, allowing us to rigorously evaluate neutron activation backgrounds and ensuring the reliability of the subsequent physics analyses.

D–D neutron flux and spectrum

The neutron flux and spectrum of the D–D neutron generator are measured and monitored using a 2″ × 2″ diameter EJ309 liquid scintillator detector. The energy linearity and resolution of the detector are calibrated by fitting the Compton edges and full energy deposition peaks of multiple radioactive gamma sources, and the parameterization is described68,69. The response matrix of the EJ309 liquid scintillator detector is simulated with GEANT4 (ref. 70), incorporating neutron interactions with the liquid scintillator, detector energy linearity and resolution and the neutron response function of the EJ309 liquid scintillator68. Neutron energy deposition is determined by applying pulse shape discrimination techniques68 to distinguish neutron signals from gamma background, leveraging the fact that neutron signals typically exhibit a longer tail in the light emission waveform in liquid scintillator. An iterative unfolding process is used using the response matrix and measured energy spectrum. Various algorithms (GRAVEL71 and MLEM72) and initial spectra (Gaussian and uniform) are tested, showing negligible differences in the unfolded neutron spectrum. Statistical uncertainties and the correlation matrix of the unfolded spectrum are obtained using the bootstrap method. The measured neutron spectrum has a peak energy at 2.5 MeV, aligning well with the simulated spectrum73 (Extended Data Fig. 3j). The detailed information on the calibration of EJ309 liquid scintillator, neutron and gamma discrimination measurements, and spectral deconvolution is provided in Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Information Note 2.

Experimental details

Before the experiment, measurements of neutrons from the neutron generator and environmental gamma energy spectra are conducted using a liquid scintillator at 87° (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). During the experiment, neutron beam monitoring is performed in the 0° and 180° directions using liquid scintillators for the D–D neutron generator beam, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 4a.

Data acquisition is conducted in two runs: run I in March 2024 and run II in July 2024. In run II, an additional detection unit is added (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Extended Data Fig. 4g,h shows the count rate variations of the Migdal detector and the liquid scintillator detector. The count rate of the liquid scintillator is normalized to the average count rate of the Migdal detector, demonstrating good consistency between the neutron beam and the detector counts. Extended Data Fig. 4e,f shows the variations in the 55Fe gain calibration during the experiment on each day. The pressure and temperature of the detector chamber are continuously monitored during the experiment, and the gas state fluctuations and good airtightness performance during the experiment are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4i–k.

Identification of NR tracks and ER tracks

Inspired by the relevant work of the MIGDAL Collaboration74, YOLOv8 (ref. 75) is applied for ER and NR recognition (training details and model performance are provided in Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Information Note 4). Considering accuracy and training speed, the YOLOv8m model architecture is the optimal choice for this study. By training, the model architecture can identify tracks in images and provide their classification and positional range information. Data annotation is performed using a platform called Label Studio, in which ERs and NRs are marked in the graphical interface. The training dataset consists of 6,000 experimental data track images and 2,400 simulated data images. For the experimental data images, half feature 55Fe characteristic X-ray photoelectron tracks, and the other half exhibit D–D source experimental NR tracks. For the simulated data images, half include electron tracks of 4–10 keV, and the other half represent NR tracks generated after the interaction of simulated 2.5 MeV neutrons with gas. The validation dataset consists of 3,000 experimental data images and 600 simulated data images, maintaining the same proportions as the training set. By training 200 epochs, the best-performing model achieves an ER identification accuracy of 99.0% and an NR identification accuracy of 99.7%. The model is then used to recognize and retain instances with both ER tracks and NR tracks, in which the distance between track clusters is less than 4 pixels, for further reconstruction and selection.

Migdal event selection algorithm

To better distinguish between NR and ER tracks for events pre-selected by the YOLO program, the following procedure is implemented. To reconstruct NRs, the average ADC value of the non-zero pixels is calculated, and the pixels with values below the average are excluded. This requirement effectively removes non-NR track from the frame, as the ADC values of the pixels along the NR are significantly higher than those of other signals. The remaining pixels are fitted with a straight line using the least squares method, and the resulting line is designated as the central trajectory of the NR track. The standard deviation \(\sigma \) of the resulting Gaussian distribution, which stands for the diffusion of NR, is then obtained. The two intersection points of the central track line with the image boundaries (x0, y0) and (x′0, y′0) are designated as initial pixel points. The endpoints of the NR track, (xn, yn) and (x′n, y′n), are iteratively refined using the centre-of-gravity method. Taking (x0, y0) as an example, with (x0, y0) as the centre and 5σ as the radius, the new centre of gravity (x1, y1) is calculated with weighted formula ADC × exp(d/d0), where d is the distance between the pixel and (x0, y0) and d0 is the pixel scale, and the centre-of-gravity method is applied repeatedly within this region until the calculated centre-of-gravity position converges between consecutive iterations.

To prevent the influence of NR tracks on the reconstruction of ER tracks, morphological erosion processing is applied to the NR track. All pixels with their centres at the midpoint between the two endpoints, at a distance of 4σ from the line, and within a radius of 4σ, are considered as the NR and removed. To ensure the remaining tracks correspond to ER signals, the ER vertex (xe, ye) is reconstructed for the residual tracks following the methodology described in ref. 76. The distance between the NR and ER is evaluated by

$$R=\fracD-4\sigma L_\rmER$$

(4)

where D is the distance between the reconstructed ER start point and one of the NR endpoints, and LER stands for the remaining length of ER after NR subtraction. Events with R > 0.5 and ER track length exceeding 5 × 83 µm are discarded, whereas all events with ER track lengths below this threshold are retained. In other words, events are retained if the reconstructed ER vertex lies closer to the NR endpoints along the ER track. To reduce the impact of edge distortion, events are ignored if the edge ADC or edge hit count exceeds 20% of the related summation value. Moreover, events are disregarded if the NR vertex is near the electron track lying within the 3σ range from the edge, or if both ends of the track hit the edge. To minimize accidental coincidences and multi-track backgrounds, events are also disregarded if there are ADC values exceeding 4σ on both sides of the fitted line for the NR. Extended Data Fig. 5 shows the track information of six Migdal candidate events in the experiments.

Quenching effect

The quenching effect in gases refers to the phenomenon in which the kinetic energy of ions is dissipated through inelastic collisions or excitation processes during their interaction with other molecules77. When ions collide with gas molecules, they transfer energy to the gas molecules, resulting in their excitation or ionization. This energy transfer process is typically inelastic, meaning the kinetic energy of the ions is converted into the internal energy of the gas molecules. In radiation detectors, the quenching effect influences the intensity and characteristics of the detection signals, causing ions with the same kinetic energy to deposit a lower detectable energy in the detector compared with electrons. The ratio between these two energies is defined as the quenching factor. We obtain the quenching factors for the working gas elements from the TRIM78 database, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 6a, and incorporate the corresponding quenching effects into the simulation of NR tracks.

Background

The background in the experiment mainly arises from three sources:

-

1.

Secondary effects from neutron recoil processes: these include delta electrons and secondary NR generated during nucleon motion, de-excitation radiation from excited nuclear states and bremsstrahlung radiation from charged particles.

-

2.

Beam-related background: this includes gamma rays produced by non-elastic collisions of neutrons, coincidental gamma rays released during the acceleration process of the neutron generator with recoil nuclei and β decay processes from neutron-activated gas atoms.

-

3.

Environmental background: this includes radioactive elements present in the air and materials, as well as coincidences between delta electrons produced by cosmic muons and recoil nuclei.

Following is the detailed discussion of the analysis of specific background components (the results of all backgrounds are shown in Extended Data Table 1).

Recoil-induced δ-ray

The background of delta electrons is estimated using experimental data. First, delta electrons near the NR tracks are identified and selected. With the requirement that the electron tracks are at least 1 mm away from the vertex, the delta electrons in the middle of the track are obtained. Then, the energy spectrum of the selected delta electrons is plotted and fitted with an exponential function. The expected count of observed δ electrons in the 5–10 keV range is 0.59 ± 0.40 over the entire experimental period. Finally, Monte Carlo methods are used to estimate the relative efficiency ratio of selecting delta electrons at the top and middle of the NR track as 0.060, and the expected background count of δ electrons during the experiment is calculated to be 0.035 ± 0.023.

Particle-induced X-ray emission

Theoretically, the maximum energy of the Auger electrons and photoelectrons of the gas is only 0.5 keV (from oxygen)79, which is barely detectable by the detector within the energy range of 5–10 keV.

Bremsstrahlung processes

-

1.

Quasi-free electron bremsstrahlung: in the Coulomb field of the recoiling ion, an electron from the nearby target atoms can be scattered, resulting in the emission of bremsstrahlung radiation80.

-

2.

Secondary electron bremsstrahlung: an electron ejected from the nearby target atoms by the impact of the recoiling ion can interact with other atoms in the target material, leading to the emission of bremsstrahlung radiation81.

-

3.

Atomic bremsstrahlung: the electron bound to the target atoms can be excited to highly bound states or to the continuum due to the impact of the recoiling ion. Subsequently, it can return to the initial state, emitting bremsstrahlung radiation82. If the electron excited to the continuum does not revert to its bound state, a phenomenon known as radiative ionization occurs, also resulting in the emission of bremsstrahlung radiation. In the analysis, the radiative ionization contribution is calculated and considered as part of the overall atomic bremsstrahlung.

-

4.

Nuclear bremsstrahlung: this process arises from the Coulomb scattering interactions between the recoiling ion and the target atoms83.

In general, the spectra of these four bremsstrahlung processes exhibit a layered structure within the continuum X-ray spectrum. Specifically, the quasi-Free electron bremsstrahlung, secondary electron bremsstrahlung, atomic bremsstrahlung and nuclear bremsstrahlung processes predominate in distinct energy regions of the X-ray spectrum84,85. The theoretical differential cross-sections for the four bremsstrahlung radiation processes induced by protons or light ions with few MeV kinetic energies are described80,82,85,86.

To estimate the expected number of electrons induced by the four bremsstrahlung processes, the expected number of X-ray emissions and the energy spectrum of X-ray emissions for each type of nucleus are estimated from the differential cross-section of bremsstrahlung. The spectrum is then input into GEANT4 to simulate the photoelectric process. A 200-μm vertex cut for NR and photoelectron is applied, and an energy cut of 5–10 keV is imposed. The resulting background expectation value is calculated to be 10−7, which can be neglected (see Extended Data Fig. 6c–f and Supplementary Information Note 3).

Random track coincidences

The random track coincidence is characterized through both data-driven and GEANT4 simulation approaches. In the experiment, the number of photoelectrons, Compton electrons and other possible processes that produce keV-level electrons occurring in the same frame as the NR tracks is estimated. The events with energy deposition in the range of 5–10 keV are selected and represented in a 2D distribution plot of dE/dX compared with circularity. Out of 8.17 × 105 collected events, a total of 63 events are identified as photoelectrons and Compton electrons. The Monte Carlo simulation is then applied to randomly distribute NRs and ERs in the same frame image. Through a selection algorithm, the accidental coincidences are identified as 0.29% of all cases. The expected yield of accidental coincidences in the dataset is then calculated to be 0.180.

Complementing this, full GEANT4 simulations evaluate three background components: (1) single-neutron-induced NR electron pairs; (2) independent neutron interactions producing separate NRs and electrons; and (3) neutron-generated NRs coinciding with gamma-induced electrons. The simulation accounted for all detector components and material interactions, with electrons (5–10 keV) and NRs (>35 keVee) selected using identical criteria to the experimental analysis. The simulated electron energy spectra show good agreement with experimental distributions (Extended Data Fig. 6b). The total simulated background of 0.156 events (0.128 single neutron + 0.019 multi-neutron + 0.009 neutron–photon) matches the data-driven estimate within uncertainties, validating our background modelling framework.

Neutron activation

GEANT4 simulations show that the production rates of unstable nuclides 3H and 14C are both less than 0.01 per million NR tracks with the energy greater than 35 keVee. Considering the half-life of 3H (12.32 years) and 14C (5,700 years), the background from neutron activation can be neglected.

Trace contaminants

The radioisotope content at natural abundances in He-DME-based gas mixtures is evaluated, including isotopes of 1H, 4He, 12C and 16O, as well as trace radionuclides such as 222Rn, 85Kr, 39Ar and 210Pb. Among the radioactive isotopes of 1H, 4He, 12C and 16O, 3H and 14C contribute almost all electrons by beta decay, with their activities in the detector being (6.38 ± 6.38) × 10−8 Bq and (4.58 ± 4.58) × 10−5 Bq, respectively. Other trace radioactive elements generate an average of (7.25 ± 0.94) × 10−7 electrons per second with energies ranging from 5 to 10 keV. The probability that these electrons have a vertex distance less than 200 μm from ions is 0.00339. Therefore, the estimated value of the trace contaminants background, normalized to the number of experimental data, is 0.00106 ± 0.00087 (see Supplementary Information Note 3, Gas radioactivity).

Muon-induced δ-rays

The measurement results of the local cosmic muon flux in Lanzhou87 is adopted to estimate the rate of δ-ray production in the detector sensitivity region. Considering the NR rate of D–D neutron source as 1 event per second, the ratio of δ-ray production and NR in the 5–10 keV energy region, accounting for the detector energy resolution, is 1.85 × 10−5. As the locations of δ-ray production and NR are both evenly distributed, their positions are randomly sampled in the detector sensitivity region based on their production rate, and a vertex distance cut of shorter than 200 μm is applied. The 73% muon exclusive efficiency of the detector is also considered in the calculation. The simulation shows that the δ-rays would contribute 0.013 events, normalized to the number of experimental data.

Secondary NR fork

The production category, rate and energy spectrum of the primary recoil nucleus are estimated by simulating the interactions of the neutron from D–D source with the DME gas with GEANT4. The primary recoil nuclei are then put into TRIM78 to simulate the following cascade process in the DME gas. The vertex distance between primary recoil and secondary recoil is required to be less than 200 μm, and the energy of secondary recoil nucleus should fall into the region of 5–10 keVee, considering the quenching factor88 of NRs. By applying the cut on the 2D distribution of track deposition energy and track length, it is able to reduce the background yield to below 10−3, while maintaining a signal efficiency of approximately 98%.

Uncertainty and significance

Background error estimation

The systematic uncertainty of recoil-induced δ-ray mainly comes from the YOLO model. The difference in the estimated yields between the two models (YOLOv8m and YOLOv8n) with different model sizes is considered as the systematic uncertainty of this background. For the systematic uncertainty of random track coincidences, both the error in the circularity and dE/dX discrimination of electrons, as well as a 10% variation in the wobble discrimination parameter, and the difference in the background yields with different YOLO models, are considered to estimate the uncertainty. The main contributors to trace contaminants of radionuclides are 3H, 14C and 222Rn. As we have used gas sealed for over a year, the gas radioactivity should be significantly lower than the atmospheric average level. The systematic uncertainty of muon-induced δ-rays consists of the uncertainties of muon flux and detection efficiency. According to the measurement results, the impact of muon flux uncertainty can be neglected, whereas the detector energy resolution contributes a systematic error of 3%. The uncertainty of εER is taken as the difference between YOLO models. The energy resolution of the NR tracks is extrapolated based on the energy resolution \(\propto 1/\sqrtE_\textdeposit\) as described in ref. 64. The energy resolution affects the counting of events selected above 35 keVee in the NR energy spectrum, and we have taken this effect into account in the systematic error of \(n_\texttot^\textNR\).

Cross-section and significance estimation

The profile likelihood method is used for significance calculation and Migdal effect probability error calculation. In this method, a probability model that depends on both the parameters of interest \(\boldsymbol\pi =(\rm\pi _,\ldots ,\rm\pi _k)\) and additional nuisance parameters \(\boldsymbol\theta =(\rm\theta _,\ldots ,\rm\theta _l)\) is used to describe the data. Denoting the density function as \(f(\bfX|\boldsymbol\pi ,\boldsymbol\theta )\), where \(\boldsymbolX=(X_,…,X_n)\) refers to independent observations, the full likelihood function can be expressed as

$$L(\boldsymbol\pi ,\boldsymbol\theta |\bfX)=f(\bfX|\boldsymbol\pi ,\boldsymbol\theta )$$

(5)

The general approach to constructing confidence intervals is to determine a corresponding hypothesis test. Here, the hypothesis test is \(\rmH_\,:\boldsymbol\pi =\boldsymbol\pi _\) versus \(\rmH_\rma\,:\boldsymbol\pi \ne \boldsymbol\pi _\), and the test can be based on the likelihood ratio test statistic:

$$\lambda (\boldsymbol\pi _|\bfX)=\frac{\sup \\bfX);\boldsymbol\theta \}\sup \L(\boldsymbol\pi ,\boldsymbol\theta $$

(6)

A standard result in statistics is that −2 log λ converges in distribution to a χ2 distribution89. Therefore, we can determine the confidence level for the hypothesis Ha: π ≠ π0 by comparing the difference between −2 log λ across various intervals and its minimum value, and then referencing the corresponding χ2 confidence intervals.

The observed counts X in this experiment follow a Poisson distribution: X ~ Pois(μ + b), where μ is the observed signal rate, and b is the observed background rate. The observed background counts Y are characterized by a Gaussian distribution: Y ~ N(b, σb). Assuming X and Y to be independent, we have

$$f(x,y|\mu ,b)=\frac(\mu +b)^xx!\rme^-(\mu +b)\cdot \frac1\sqrt2\rm\pi \sigma _b\exp \left(-\frac(y-b)^22\sigma _b^2\right)$$

(7)

Here, the hypothesis test is H0: μ = 0 versus Ha: μ ≠ 0. This model can be implemented using the model 5 in the TRolke library of CERN ROOT90 to directly compute the profile likelihood function −2 log λ, the results of which are shown in Extended Data Fig. 7a. The minimum of this likelihood function occurs at \(\mu \) = 5.77, and the corresponding 5σ value is greater than 0, providing significant evidence for the existence of the Migdal effect.

For the estimation of the upper and lower limits of the cross-section probability errors, the profile likelihood method is also used. It is important to note that the calculation of the cross-section probability must account for the signal efficiency. Therefore, the observed counts X in the signal region are modified to X ~ Pois(en + b), where e is the signal selection efficiency and n is the number of Migdal events generated. The background counts Y remain characterized by Y ~ N(b, σb). Moreover, the signal efficiency is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution: Z ~ N(e, σe). The profile likelihood function for this model can also be directly computed using model3 in the TRolke library. The resulting likelihood function, along with the positions of the minimum nmin and its lower and upper limits nll and nul, are shown in Extended Data Fig. 7b. The error propagation is applied as follows:

$$\Delta P_\pm =\sqrt{\left(\fracn_\min -n_\mathrmul/\mathrmlln_\min \right)^2+{\left(\fracn_\mathrmtot^\mathrmNR_\mathrmerrorn_\mathrmtot^\mathrmNR\right)}^2}\times \fracn_\min n_\mathrmtot^\mathrmNR$$

(8)