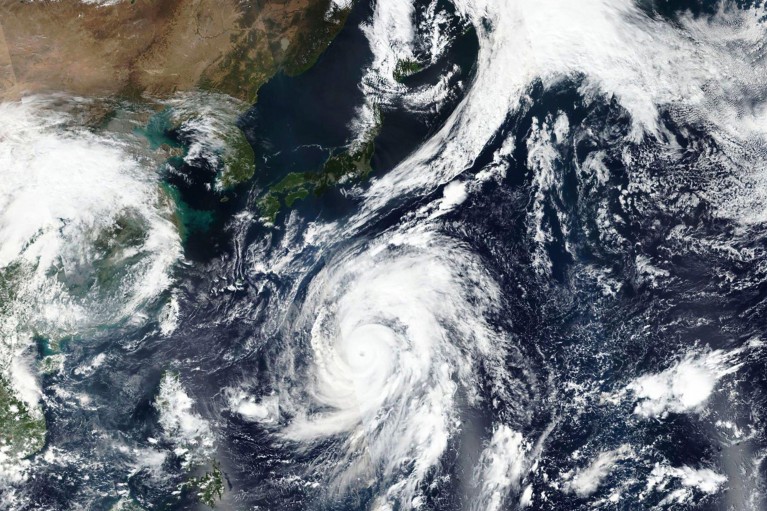

Typhoon Hagibis approaches Japan in 2019. The storm was one of the events used to study the accuracy of an AI-based forecasting system.Credit: NASA Worldview, Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS)/AP/Alamy

Google DeepMind has developed the first artificial intelligence (AI) model of its kind to predict the weather more accurately than the best system currently in use. The model generates forecasts up to 15 days in advance ― and it does so in minutes, rather than the hours needed by today’s forecasting programs.

The purely AI system beats the world’s best medium-range operational model, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts’ ensemble model (ENS), at predicting extreme weather such as hurricanes and heatwaves. The breakthrough could help usher in an era of AI weather forecasting that is quicker and more reliable than today’s systems, researchers say. The system, called GenCast, is described today in Nature1.

Superfast Microsoft AI is first to predict air pollution for the whole world

Conventional forecasts, including those from ENS, are based on mathematical models that simulate the laws of physics governing Earth’s atmosphere. They use supercomputers to crunch data from satellites and weather stations ― a process that takes hours and vast amounts of computing power.

GenCast, by contrast, has been trained only on historical weather data, which enables the system to draw out complex relationships between variables such as air pressure, humidity, temperature and wind. This helps it to outperform strictly physics-based systems, says Ilan Price, a research scientist at Google DeepMind in London and an author of the paper.

“We’ve really made dramatic progress to catch up and now overtake [physics-based models] with machine learning”, Price says.

AI surge

AI weather forecasting has advanced rapidly, with multiple companies racing to develop new and better models. Among them are Huawei2 in Shenzhen, China, and Nvidia in Santa Clara, California. Earlier this year, Google released NeuralGCM3, a hybrid system that combines physics-based models with AI to produce short- and long-term forecasts on a par with conventional models.

Some of the AI systems released to date are ‘deterministic’ models, meaning that they offer only a single forecast and do not estimate the likelihood that the forecast will be correct. By contrast, GenCast generates ‘ensemble’ forecasts: a suite of forecasts that have each been produced from slightly different starting conditions. By combining these forecasts into an ensemble, scientists can produce a final forecast and estimate the probability that the forecasted weather will occur.

How machine learning could help to improve climate forecasts

Price and his colleagues trained the AI on global weather data from 1979 to 2018 and then predicted the weather of 2019. To check its accuracy, they compared GenCast forecasts with actual weather data and ENS forecasts for that year.

GenCast was more accurate than ENS on 97% of the measures used on a scorecard to evaluate such ‘probabilistic’ forecasts. It was also better at forecasting extreme heat, cold and wind, as well as tropical-cyclone tracks.

GenCast produces one 15-day forecast within 8 minutes on an AI processing chip. This speed is “quite substantially faster” than the time it takes conventional models, Price says.

Code for all

The researchers have released the underlying code and are making model parameters called ‘weights’ available for non-commercial use. Price says this will help to “democratize” research and increase public access to weather modelling.

“This is a really great contribution to open science,” says Matthew Chantry, a machine-learning coordinator at the European Centre For Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in Reading, UK. “We need to understand how these models perform in the most extreme weather events”, and publishing the model and data publicly will allow the research community to assess them, he says.

Chantry read a manuscript of the paper when it was posted on a preprint archive last year and was inspired by GenCast’s ‘diffusion’ approach, which introduces random noise into the model to refine its reliability. “We’ve actually implemented some of the key breakthroughs in our own machine-learning model,” he says. The resulting model, called Artificial Intelligence/Integrated Forecasting System (AIFS), will be published soon, he adds.

Having more accurate forecasts sooner can help people make informed decisions, Price says, especially for those living in the path of a hurricane.