Duplicated text and unusual statistics have been flagged in 130 studies by a single physician-researcher and his co-authors.Credit: Getty

A team of scientist–sleuths has flagged data-integrity concerns in 130 studies authored by the same biomedical researcher, a specialist in women’s health and gynaecology, and his colleagues. The sleuths published their findings in a peer-reviewed paper earlier this year1.

Some of the studies that were identified as potentially problematic have been cited by other researchers or included in analyses that could inform clinical practice. The number of papers being questioned is among the highest by a still-active life-scientist, say some specialists.

The 130 studies were published between 2014 and 2023 and report the results of clinical trials and other research on maternal and women’s health. The highlighted problems include oddities in reported statistics, unfeasible results and text that is identical to other papers. Ahmed Abbas, an obstetrician and gynaecologist at Assiut University in Egypt, is listed as a co-author or corresponding author for all 130 articles. Abbas did not respond to Nature’s request for comment.

Biomedical paper retractions have quadrupled in 20 years — why?

Some of the papers remain part of the literature. Eleven have been retracted. Before it was retracted, one of those 11 was included in a 2019 meta-analysis on a treatment to prevent miscarriage. The retractions of the paper by Abbas and his team and another, unrelated paper will probably change the conclusion of the analysis, says one of the 2019 work’s authors.

The inclusion of a potentially unreliable study in a systematic review can have harmful consequences, because “it can immediately affect how a surgeon or an [obstetrician–gynaecologist] is doing their job”, says James Heathers, a forensic meta-scientist at Linnaeus University in Växjö, Sweden, who was not involved with the investigation that identified the data-integrity concerns.

Women’s health specialists are actively developing strategies to prevent the publication of questionable data. But they say that once these papers are published, it’s difficult to purge them from the literature.

Alaa Mohamed Ahmed Attia, the dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Assiut University, with which Abbas is affiliated, did not respond to Nature’s request for a comment on the concerns raised about Abbas’s publications in this year’s peer-reviewed paper.

Rejection and retraction

The 130 flaggedstudies were described in a paper published in May1 in the Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction by obstetrician and gynaecologist Ben Mol, at Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and his colleagues.

In 2016, Mol peer-reviewed an unpublished manuscript co-authored by Abbas about a clinical trial of the hormone progesterone to prevent miscarriage. Mol noticed discrepancies in the paper and notified the journal, he says. The journal rejected the work by Abbas and his team. But in 2017, a different journal, The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, published a version2 of the manuscript that included changes to the sections that Mol had flagged, he says. The journal ultimately retracted the paper in December 2019.

According to the retraction notice, the journal’s editors-in-chief learnt that previous versions of the manuscript “showed significant changes to the underlying data.” The notice also said that when contacted, the authors could not provide the original data to verify the results. According to the journal’s publisher, Taylor & Francis, concerns about the paper were first raised in February 2019. The resulting investigation led to the article’s retraction later that year, the publisher says. Abbas did not respond to Nature’s request for comment about the retraction.

Massive database

Mol’s team decided to survey all papers by Abbas with the exception of literature reviews, case reports and studies done as a part of an international collaboration. They identified 263 papers that included Abbas as an author. These studies collectively enrolled more than 74,000 participants between 2009 and 2022.

Of the 263 studies analysed in the paper, 130 — almost half — raised the sleuths’ concerns. Some of the papers had statistics that seemed unfeasible. One used wording that was similar to that of a previously published paper. The articles that the team flagged appeared in journals produced by several publishers such as Taylor & Francis and Springer Nature, which also publishes Nature. Nature’s news team is editorially independent of its publisher. When asked for comment by the news team, Springer Nature did not respond.

The sheer number of studies that were claimed to have been produced in such a short period of time caught the attention of Mol’s team. According to the reported registration and publication timeline of the papers, in May 2017, Abbas would have been conducting 88 simultaneous clinical studies. Catherine Cluver, a gynaecologist and obstetrician who leads the preeclampsia research unit at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, agrees with Mol’s team that it seems unfeasible to conduct such a large number of studies at one time. “Doing all of the regulatory work, the ethics approvals, making sure the trials are being run correctly … I think there is no way you could do more than four or five, and even then, it’s a push,” she says.

Concern over numbers

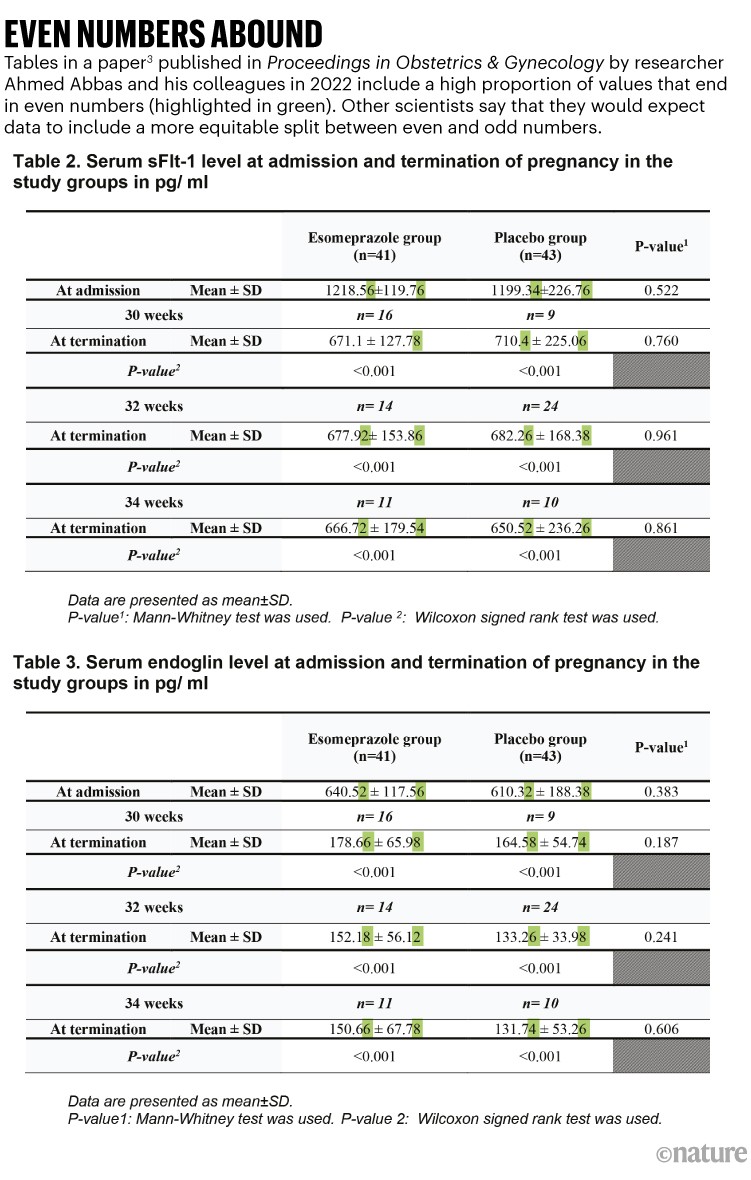

A common issue identified by Mol and his colleagues was statistical oddities. One paper they flagged, published in the journal Proceedings in Obstetrics and Gynecology3, evaluated the effect of the medication esomeprazole in women with the pregnancy complication preeclampsia. The sleuths noted that the last digit of 31 of the 32 values in tables 2 and 3, including means and standard deviations, are even numbers (see ‘Even numbers abound’). In scientific data, the digits of such measurements and statistical results tend to be more equally distributed between odd and even numbers, so the chance of having so many values ending in even numbers would be low. The numbers are a “concern”, according to the paper by Mol and his team.

Source: Ref. 1

The tables also feature numerous pairs of numbers that have identical digits after the decimal point — for example, 0.76. Some of the repetitious values are in the same table; some are split across the tables. This, too, is concerning, says the paper by Mol and his team.

These unusual numbers should compel the authors to present their raw data, says Nicholas Brown, a psychologist and research-integrity specialist at Linnaeus University.

The editor-in-chief of Proceedings in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Donna Santillan, said in a statement that all inquiries about research or publication misconduct are investigated by the journal. Santillan, a reproductive sciences researcher at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, declined to comment on whether this study is currently being investigated, citing privacy concerns.

Continuing investigation

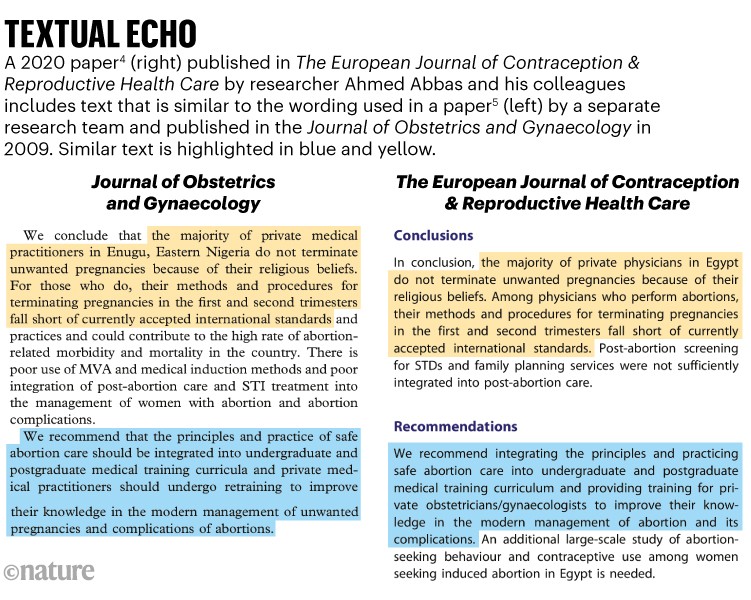

Other studies flagged by Mol’s team describe apparently improbable results. In a 2020 survey4 in The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care that assessed the attitudes of obstetricians and gynaecologists in Egypt towards abortion, for example, the mean age of physicians surveyed was 42.6, and their mean number of years in practice was 26.4. For these numbers to be correct, the mean age at which these physicians started practicing would be 16.2. The same paper contains phrases that are identical to those of a study5 published in 2009 by different authors (see ‘Textual echo’).

Source: Ref. 1

The journal’s publisher, Taylor & Francis, says that it is currently investigating the paper, after concerns were raised in December 2023. Abbas did not respond to a request for comment about the investigation.

Mol says that he is not accusing the authors of data fabrication and it’s possible that the discrepancies are a result of unintentional errors. “We’re just presenting the facts and then other people can draw a conclusion.”

Clinical-trial checklist

Some publications that specialize in women’s health told Nature that they are actively working to keep problematic research from being published. For example, a group of journal editors are fighting against data falsification in the field of obstetrics and gynaecology by sharing information about potentially flawed papers. The group also drew up a checklist of seven requirements that randomized controlled trials must meet to be published, such as ethics-committee approval. If a trial’s authors don’t fulfil these requirements, “we’re not going to publish it”, says Vincenzo Berghella, editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine and a maternal-fetal specialist at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

How a data detective exposed suspicious medical trials

If problematic studies do end up in journals, investigating them post-publication can be a “painstakingly difficult” process, says Žarko Alfirević, a specialist in fetal and maternal medicine at the University of Liverpool, UK. “The burden of proof needs to be enormously high” for journals to admit that fraud has been committed, he says.

To mitigate the damage of problematic studies in the medical literature, Alfirević, who is an editor at Cochrane, a group that reviews medical evidence, is pushing for the adoption of trustworthiness assessments of randomized controlled trials as a condition for authors to include them in systematic reviews.

Downstream effect

The risk of flawed papers affecting medical care is real, says Mol. One example is the 2017 study by Abbas and his colleagues on the use of progesterone to prevent miscarriage and the 2019 systematic review in which the study was included. That same review by Cochrane also incorporated a second study, authored by a different group, that was also subsequently retracted. Both papers contributed to the review’s conclusion that progesterone supplements might reduce the risk of miscarriage in women who have experienced recurrent miscarriages. The review has been cited in ten clinical guidelines.

Now it’s clear that, despite what the retracted studies suggested, the supplements are not effective for all women who have experienced recurrent miscarriages6. The review’s corresponding author, David Haas, an obstetrician and gynaecologist at Indiana University in Indianapolis, says that it is “highly likely” that the two retractions will change the review’s conclusion. He and his colleagues are now working to publish an updated version of the review in which the retracted studies have been removed. A notice on the current online version of the review says that the review authors have been advised that the study by Abbas and his colleagues is the subject of investigation and the review team has moved the study from ‘included studies’ to ‘studies awaiting classification’.

How papers with doctored images can affect scientific reviews

Another review that included a paper authored by Abbas and his colleagues is also being updated. The meta-analysis7, published in 2023, analysed papers on a strategy combining progesterone and a procedure on the cervix to prevent pre-term birth and concluded that the combination could be successful. Among the papers analysed was a study8 by Abbas and his co-authors, which was published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics in 2020.

The journal retracted the paper in late 2023, noting that “inconsistencies were found within the dataset … which call into question the validity of the data.” The authors of the meta-analysis say they are aware that Abbas’s paper has been retracted and they are about to submit an amended version that excludes the retracted work. “Fortunately, removing this paper from our meta-analysis has not influenced the primary outcome,” says corresponding author Craig Pennell, an obstetrician and gynaecologist at the University of Newcastle in Australia.