When surgeons removed a 33-year-old woman’s right lung as part of her cancer treatment in 1995, they expected a dramatic and permanent reduction in her breathing power. But that’s not what happened. Instead, her remaining lung pulled off a trick that scientists had long thought impossible in humans: it grew new tissue, and lots of it. Over the next 15 years, her left lung compensated for the loss of its partner by nearly doubling in volume and growing millions of new air sacs, called alveoli1.

“Until then, the prevailing view was that lungs are not really regenerative,” says Purushothama Rao Tata, a biologist at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina. “But in my view, lungs are not really different from liver,” he says. “Lungs have tremendous regenerative capacity.”

Nature Outlook: Lung health

Over the past decade or so, researchers have started exploring the regenerative abilities of the lungs in earnest. The findings are changing how scientists see the organ. It is becoming clear that lungs, although quiescent when undisturbed, are able to react and respond to injury or infection, thanks to specialized cells that have a surprising ability to morph from one type to another. Faults in this process are also emerging as key mechanisms behind lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), raising the intriguing possibility that this currently incurable condition could be slowed, stopped or even reversed.

Such treatments are sorely needed. “COPD is the third leading cause of death in the world,” says Ed Morrisey, a biologist who studies lung development and regeneration at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “And yet we don’t have any really good therapy.” For other diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) — a fatal condition in which the lungs become progressively scarred and stiff — the outlook is similarly bleak. Even with a lung transplant, respite from IPF is usually only temporary because recipients often don’t survive for longer than about five years. Researchers hope that the hitherto overlooked ability of the lungs to rebuild themselves might hold answers.

Hidden potential

One reason that the adult human lung’s ability to regenerate flew under the radar for so long is because it can partly compensate for lost tissue by drawing on physiological spare capacity. Age is another. Young mice and rats, for example, rapidly grow extra tissue when one lung is removed, but this ability declines as the animals get older. Young children can regrow some lung tissue. This is possibly related to human lung development continuing after birth and into the teenage years. But, as with rodents, this ability seems to diminish with age. What’s more, surgery to remove lung tissue is usually performed on older adults. Lung recovery is not followed up long-term, meaning signs of regeneration would be missed.

Yet, it has long been clear that the lung must have some repair capacity — after all, people routinely recover from lung injury caused by viral infections, such as influenza. By the early 2000s, researchers were developing the tools to explore lung regeneration in detail. Pioneering work by developmental biologist Brigid Hogan and her team at Duke in 2009, for example, definitively established2 that basal cells in the lung airways act as stem cells, which can generate specialized cell types. Reports of lung regrowth in humans (including in the 33-year-old woman with cancer) followed. And around the same time, research on the mouse lung showed how stem cells contribute to regeneration.

Thanks to innovations, such as ‘omics’ technologies for studying gene activity in space and time; advanced cell-culture techniques, including keeping human lung slices alive; and 3D mini-lung structures grown from stem cells, called organoids, discoveries have multiplied at pace. Cell atlases3 of healthy and diseased lungs have identified about 70 predicted cell types and linked specific types to genes involved in COPD and fibrosis.

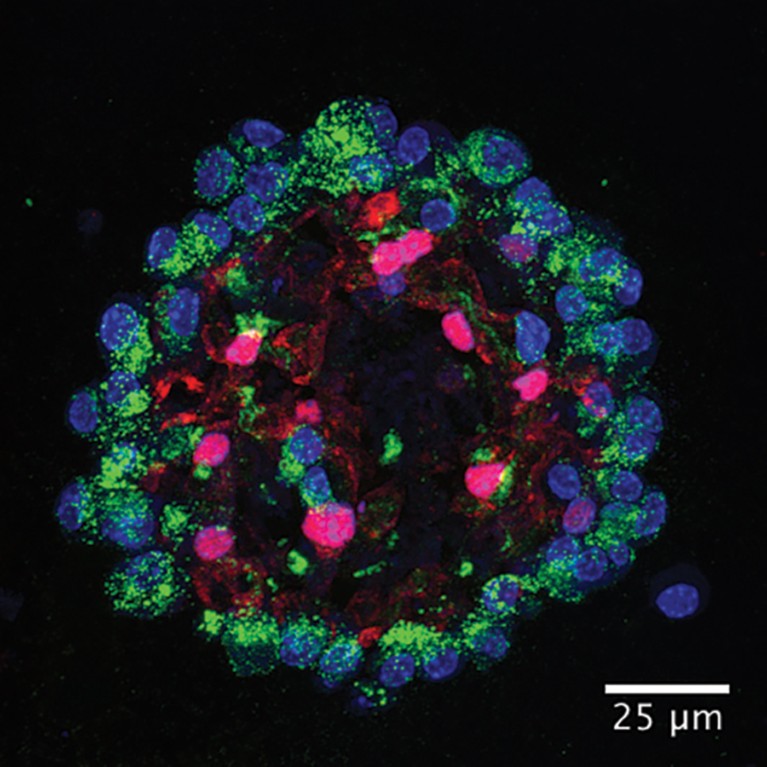

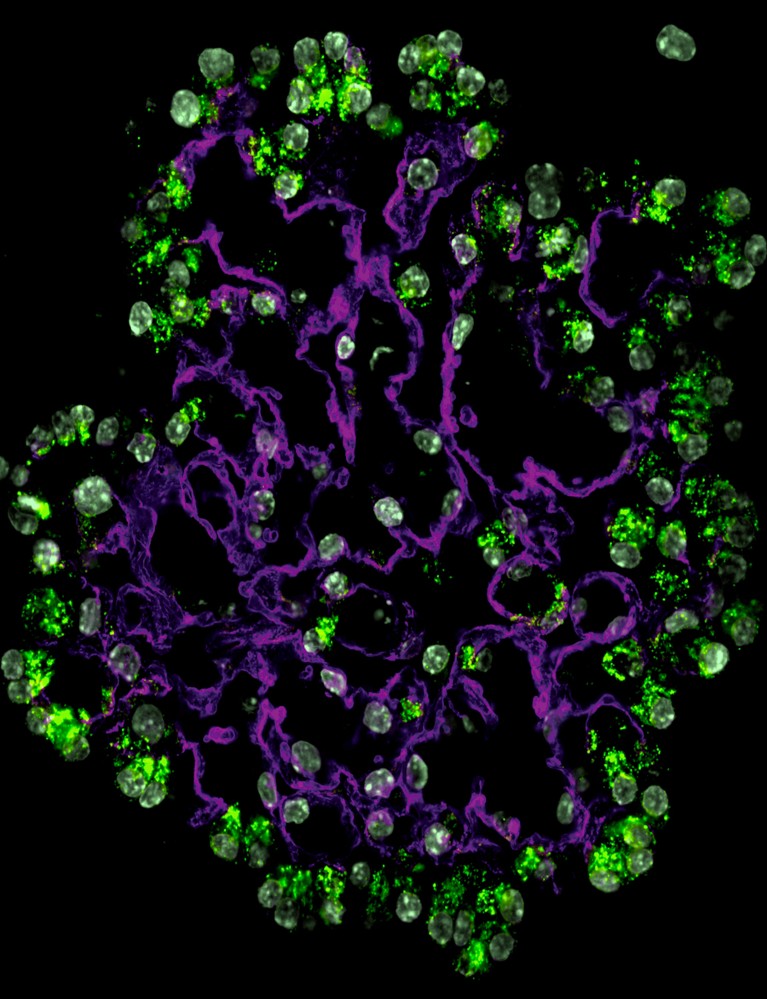

Human lung organoid.Credit: Ziqi Dong/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.09.007

One surprise that emerged from these studies is that lung cells are extraordinarily flexible, says Ana Pardo-Saganta, a stem-cell biologist at the Institute for Lung Health in Giessen, Germany. Other organs rely on a small population of dedicated stem cells for repair. The lung, by contrast, contains differentiated cells that have not only have specialized functions but also the flexibility to switch identities and serve as stem cells if the need arises. “That’s amazing,” says Pardo-Saganta. “We were underestimating the capacity of the lung.”

An important example of this flexibility, or plasticity, lies in the lung’s balloon-like alveoli. Each alveolus comprises an ultra-thin cell called AT1. This cell takes up 95% of the alveolus and interfaces with blood capillaries to facilitate gas exchange. Another cell, AT2, occupies the remaining 5%. Its day job is to produce surfactant to lower the surface tension in the alveolus. But if the AT1 cell is injured, the AT2 can moonlight as a stem cell that produces an AT1 cell4. Tata and his team have studied this transition by following gene-activity patterns in alveolar cells as they repair an injury. These techniques allow researchers to predict not just cell type, or specialized function, but also what the cell is doing at any particular time. The researchers found that rebuilding alveoli relies on finely tuned crosstalk between AT2 cells and another kind of cell called an alveolar fibroblast5.

Alveolar fibroblasts reside in the space, or interstitium, between alveoli. They are responsible for generating the stretchy molecular scaffold, or extracellular matrix (ECM), that supports lung cells. After injury, Tata says, the alveolus undergoes extensive remodelling, in which areas of thickened interstitium exist next to areas of enlarged alveoli with thin interstitium. In healthy regeneration, these areas resolve into normal structures.

Cellular role play

But lung-cell plasticity is a double-edged sword. More flexibility creates more opportunity for faults, resulting in abnormal regeneration. Evidence suggests that this is what occurs in COPD and fibrosis. In early COPD, the small airways of the lungs, the bronchioles, become inflamed, thicker and stiff. Later, the interstitium of the alveoli becomes thin and weak. As a result, the air sacs enlarge and break down, resulting in emphysema. In fibrosis, the opposite happens: the interstitium becomes thickened and stiff.

These disruptions to the interstitial ECM look similar to the normal remodelling process, says Tata. To find out more, he and his team examined what happened if they manipulated the genes that changed activity in the cell states that the researchers had observed in AT2 cells and alveolar fibroblasts. They found that normal rebuilding requires these states to exist only transiently. When Tata’s team forced AT2 cells to maintain transitional genes, the fibroblasts persisted in their remodelling state, producing excess ECM and causing fibrosis. Conversely, blocking transitional genes prevented the formation of the remodelling fibroblasts. This caused ECM production to drop, creating emphysema-like changes.

These findings suggest that both emphysema and fibrosis stem from the same faulty regenerative mechanism, with environmental factors, genetics or chronic injury tipping the balance towards different outcomes. Tata’s team is focusing on targeting cell states to return a diseased system back to a healthy balance.

Similar discoveries — of crosstalk between epithelial cells and fibroblasts helping the lungs to maintain the right balance during regeneration — have emerged from Morrisey’s lab. His team has identified molecular signals that are secreted by lung fibroblasts and picked up by epithelial cells6. Other teams have shown that abnormal cell plasticity in IPF results in alveolar cells adopting abnormal cell states and switching types to become airway cells, hindering regeneration7. These results point to a local community of cell types, including immune cells, that need to work together either to maintain healthy tissue or to regenerate.

Alveolar organoids showing alveolar type-2 (green) and alveolar type-1 cells (magenta) and nuclei (blue).Credit: Tata lab, Duke University.

The physiology of the lung itself is also key. For example, researchers, including Morrisey, have shown that stopping the expansion and contraction of the lung that happens during breathing causes AT1 cells to switch identity and become AT2 cells. These breathing-induced forces diminish in people with stiff fibrotic lungs — a change that probably exacerbates the progression of the disease.

Oxygen levels, too, affect lung-cell plasticity. At the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge, UK, developmental biologist Emma Rawlins found that low levels of oxygen help to direct lung-cell differentiation during development — but that chronic hypoxia induces differentiated human AT2 cells to switch fates to become airway cells, mimicking the bronchiolar switch seen in IPF. Hypoxia is prevalent in chronic lung diseases, such as fibrosis, meaning that the two factors might work together to promote disease progression8. The emerging picture is that of an intricate and dynamic system.

Consequently, researchers who are looking to slow or reverse chronic lung disease are studying tissue-level interventions. Researchers know of, and can manipulate, some molecular communication signals, but targeting them to the right cells at the right time is a significant barrier. Tata’s team, for example, is identifying chromatin features that are unique to conditions such as IPF as a way to target therapeutics, such as peptides, that can modulate gene activity in cells.

These approaches are a radical departure from conventional medicine. Rather than giving a single intervention, therapies will probably involve sequential steps of different treatments to coax lung cells back into healthy states. “We have a lot of basic science to do up front,” says Morrisey.

Researchers, including Rawlins, are looking to embryonic development for clues about lung regeneration. She hopes to correct aberrant cell behaviour to reset normal regeneration or, in advanced disease, re-initiate developmental processes to rebuild alveoli that are sufficient to improve a person’s quality of life.

A number of hurdles lie between her and this goal, including the limitations imposed by lung-research models. Important biological differences exist between mice and humans, and organoids can recapitulate only a few cell types. “You can’t build a lung in a dish in a way that the body does it in vivo,” says Rawlins.

Breaking the age barrier

More immediate therapeutic developments look set to emerge from efforts to remove a key barrier to regeneration: ageing. COPD and fibrosis are mainly diseases of older people, and both are characterized by a cell state known as senescence.

Senescent cells stop dividing but remain metabolically active, secreting molecules involved in inflammation and repair. They are key to many chronic and acute lung diseases, including COVID-19. In healthy tissues, immune cells clear away senescent cells once repair is complete. If the senescent cells persist, however, their signals can become damaging, perpetuating chronic inflammation and even prompting other cells to become senescent, too. This disrupts healthy cells and contributes to changes in tissues, such as fibrosis. Senescent AT2 cells, for example, don’t differentiate into AT1 cells, hindering regeneration.

Senescent cells accumulate naturally over time, but external factors can accelerate the process. Chronic oxidative stress from cigarette smoking, pollution or infections can trigger senescence, creating chronic, mild inflammation in the lung. “We believe that this inflammation is driving disease progression,” says Peter Barnes, who studies lung disease at Imperial College London. Senescent cells release packages called extracellular vesicles that, like sparks from a wildfire, spread senescence to other cells. In the lung, these vesicles can be transferred from epithelial cells to fibroblasts in the airways9.

This all suggests that removing senescent cells could restore the regenerative abilities. Drugs that either kill senescent cells (called senolytics) or inhibit their development or function (known as senomorphics) are being explored for treatment of chronic lung disease. Clearing senescent cells with a senolytic drug in a mouse model of COPD, for example, has been shown to reverse emphysema10.

Clinical trials are in early stages. Preliminary studies of the senolytics dasatinib and quercetin in people with IPF, for example, showed that the drugs were well tolerated and could proceed to phase II trials. And the diabetes treatment metformin is under investigation for its potential senomorphic properties. A key consideration for the development of such drugs is that healthy AT2 cells undergo a senescence-like stage when producing AT1 cells, says Pardo-Saganta. That means that the senolytic targeting or timing will need to be carefully tailored to avoid inhibiting normal regeneration, she says.

Lessons from the pandemic

Although a lot of lung-regeneration work focuses on chronic disease, it is also highly relevant to acute infections such as influenza and COVID-19, which can cause fibrosis — especially in older people. Both airway and alveolar stem cells are targets of coronavirus infection, says Huaiyong Chen, who studies the effects of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 on lung regeneration at Tianjin Haihe Hospital in China. SARS-CoV-2 also damages the cells that support stem cells, further hindering regeneration, Chen adds.

Monitoring lung regeneration at the level of individual cells would transform prognosis and tailored treatment. Currently, physicians rely on clinical assessments, which Chen says are imprecise. His team is exploring whether tracking biomarkers that cells releases into the blood could be used to monitor damage. This would help to predict the course of a person’s illness, such as how likely it is that cellular injuries might tip regeneration towards fibrosis. Biomarker tracking could also help to monitor the long-term recovery of the lung, which can take many months. The challenge will be integrating the large number of potential biomarkers with clinical data to make them meaningful, Chen says.

Beyond COVID-19, infections such as influenza can have a long-term impact on the lung that regenerative medicine could address. Morrisey’s team has found that a single infection with influenza can cause permanent changes to cellular gene activity in the lungs of mice that are reminiscent of aberrations found in degenerative lung disease11. “The tissue still bears memory of these encounters,” says Morrisey. “My guess is over time, the accumulation of these cell states that are from previous injuries make the tissue less responsive later on.”

How the lung is viewed has changed considerably in a short time — from quiescent organ to poster child for cell plasticity and regenerative medicine. But there’s a long way to go if science is to translate that potential into treatments that could transform lives. “Respiratory medicine has just been really tough,” says Morrisey. “We just don’t understand the organ that well yet.”