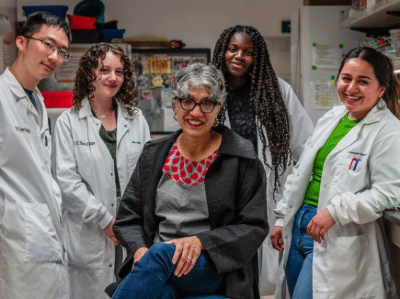

Sonia Guimarães at the Aeronautics Institute of Technology in São José dos Campos, Brazil is a fierce advocate for Black girls to pursue careers in science.Credit: Dalila Dalprat/Personal Archive

Sonia Guimarães’s life is full of firsts. In the 1970s, as a physics student at the Federal University of São Carlos in Brazil, she was the first in her family to attain a university degree. In 1989, she finished her doctorate in electronic materials at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, UK, becoming the first Afro-Brazilian woman to earn a doctoral degree in physics. And in 1993, she became the first Black woman to join the faculty at the Aeronautics Institute of Technology in São José dos Campos, Brazil — a military higher-education institution, where she is still affiliated.

Since early in her career, Guimarães has worked with semiconductors: from using these devices to build solar cells to developing the thinnest internal electrical layers possible so as to miniaturize the devices.

In 2020, she obtained a patent for the development of a ballistic sensor, which detects infrared radiation produced by airborne plane engines. The technology, she says, is unique in Brazil and was supposed to aid the country’s air force. As a Black woman, Guimarães has faced several hurdles throughout her career and has become one of the most outspoken champions of gender and racial equality in Brazilian science.

I help to build support systems for Latina researchers

Guimarães is an advocate for Black scientists on many fronts. Besides being a member of the Brazilian Association of Black Researchers, she is a founding councillor for the Afro-Brazilian Society for Socio-Cultural Development — a non-governmental organization dedicated to promoting visibility and improving the socioeconomic status of Black people in Brazil — and presides over the Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Commission of the Brazilian Physics Society.

She also mentors girls in science, working with programmes including Investiga Menina! (Research, Girl!), a project in Goiás state aimed at getting Black girls involved in science; Futuras Cientistas (Future Female Scientists), a nationwide project focused on secondary-school students; and Pesquisa para Elas (Research for Them), a free online programme of science immersion for teenage girls. Last year, Guimarães started working with Sementes Afrodescendentes (AfroDescendant Seeds), a project focused on anti-racist education in schools in São José dos Campos. She tells Nature’s Careers team why anti-racism work leads to better scientific solutions for society.

What is your great passion as a scientist?

The creation of new and fantastic things. When I started, millions of years ago (giggles), semiconductors were the beginning of everything. There were no mobile phones. There was one computer in the entire university, and it was the size of a huge room. So, as a second-year undergraduate in physics, my professor, physicist Jorge Swieca, introduced me and some of my peers to semiconductors. He told us that these materials could conduct electricity, or resist it – and depending on how they’re made, they can conduct currents precisely when and how you want. I remember him saying that semiconductors were going to be the basis of all technological development that would exist in the future. Bingo! I never looked back.

Who has been your biggest influence or mentor and why?

Professor Swieca gave me the idea of what I was going to do when I grew up. But the person who gave me all the encouragement to overcome the hardships I faced was my mother. When I was about ten years old, my father, an upholsterer, died of tuberculosis. My mother was left with four children to feed and no husband’s salary to count on. But she was ingenious.

Once, a neighbour’s daughter was getting married, and her baker bailed on her a week before the wedding. The neighbour knew my mother had made a cake here and a snack there, and asked for her help with the catering for 100 guests. My mother took it head on: she gathered all my sisters and everyone she knew to make it happen. This is where my mother’s catering business started. It still exists, run by one of my sisters. With money from this business, my mother sent me to university. She paid for my living costs so that I didn’t have to work.

I must have picked up this ‘can do’ attitude from my mother. I can’t drop the ball, otherwise she gets very angry!

Why is anti-racism work important to science?

The world needs solutions for everyone, not just for men, and for people with white skin. And we’re running out of time for answers. When science excludes certain groups, we’re faced with uncomfortable, bizarre situations. For example, some oximeters don’t read blood oxygen levels accurately for dark-skinned people — who then can’t know for certain whether they have COVID-19, say, because the equipment was designed for light-skinned people. That’s stupid.

Collection: Changemakers in science

Scientific progress stalls if only one type of person is looking for solutions. Many groups need to be involved — not just in physics, but in chemistry, mathematics, medicine, engineering, automobile science and everything else. Women are more likely to die in car accidents, even if the accident isn’t very serious. Why? Because test dummies are mostly based on male body size and shape. Women’s breasts are completely overlooked in car safety design.