Metallohydrolases catalyse some of the most difficult hydrolysis reactions in biology by using their bound metal ions to activate a water molecule positioned adjacent to the substrate bond to be cleaved16,17,18. Engineering new metallohydrolases is currently of considerable interest for degrading human-generated environmental pollutants, for which there has not been sufficient time for efficient hydrolytic enzymes to evolve19,20,21. Protein engineering has expanded the scope of substrates that can be hydrolysed by metallohydrolases, but this often requires initial promiscuous activity22,23. De novo enzyme design has been used to generate new metallohydrolases6,10,24, but these have had relatively low activity and efficiency, and have required extensive directed evolution to match the activity and efficiency of native enzymes24. Given an ideal metallohydrolase active site, de novo enzyme design seeks to identify or generate a protein scaffold that positions the catalytic residues, metals, and substrates in optimal catalytic geometries with high accuracy25,26. RFdiffusion has been used successfully to scaffold active sites, but the search has been limited by the need to specify the sequence positions and conformations of the catalytic residues8,9,27.

We reasoned that a generative artificial intelligence design method that only required the specification of side-chain functional group positions around a reaction transition state, and was capable of sampling over all possible sequence positions and conformations of these residues, could more readily satisfy complex catalytic constraints14,15,28,29. We set out to develop such an approach, and used it to design new metallohydrolases starting from a quantum chemistry-generated active site description with a bound metal cofactor.

To enable sequence-position and side-chain rotamer-agnostic enzyme design, we developed a generative artificial intelligence flow-matching model called RFdiffusion230. RFdiffusion2 extends the capabilities of RFdiffusion to generate scaffolds that position a set of functional residues (a ‘motif’) in two key ways. First, it enables atomic substructure scaffolding: RFdiffusion can only scaffold backbone-level motifs (with the side-chain and backbone atom N-Cα-C=O positions specified), whereas RFdiffusion2 can scaffold arbitrary atom-level motifs (any subset of amino acid heavy atoms). This is important for enzyme design because it allows users to specify only the positions of the key functional groups that interact with the reaction transition state, rather than the full side-chain and backbone conformation. Second, RFdiffusion2 enables sequence-position-agnostic scaffolding: RFdiffusion requires specification of the primary sequence positions of the motif residues, but RFdiffusion2 can scaffold motifs whose primary sequence positions are unknown. RFdiffusion2 replaces diffusion with flow matching31,32 and achieves sequence-position-agnostic atomic substructure scaffolding by providing randomly selected native atomic coordinates (but not their sequence positions) during training in addition to the partially noised, sequence-labelled atomic coordinates. With these improvements, RFdiffusion2 generates diverse proteins starting directly from catalytic configurations that consist of input functional group positions and substrate coordinates. Allowing the model to resolve the a priori unknown degrees of freedom (that is, the primary sequence positions and side-chain rotamer conformations of the catalytic residues) is considerably more effective at generating self-consistent design solutions than randomly sampling those degrees of freedom before inference, because the space is far too large to enumerate, as was necessitated with RFdiffusion. A detailed description of RFdiffusion2 training and benchmarking results for a wide range of active site scaffolding problems is described elsewhere30.

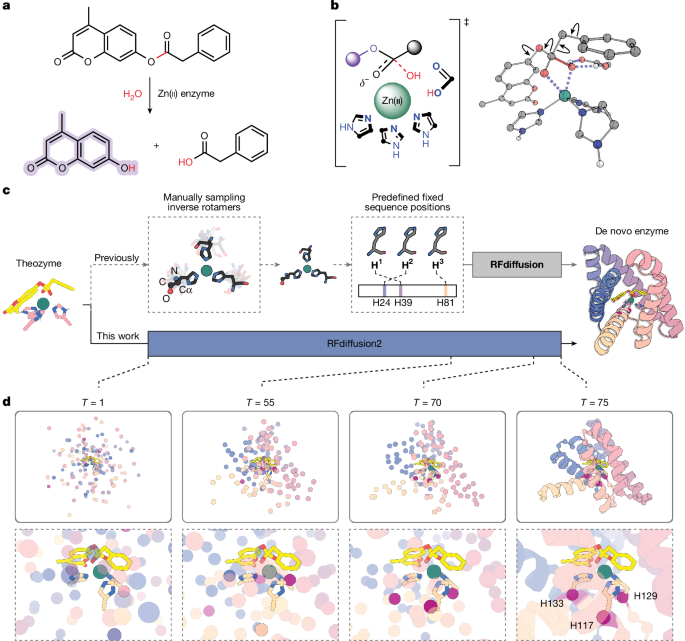

As an initial test of RFdiffusion2, we chose to design a zinc metallohydrolase for the hydrolysis of a fluorogenic ester, 4-methylumbelliferyl phenylacetate (4MU-PA), as a target reaction (Fig. 1a). We began by using density functional theory (DFT) to identify the transition-state geometry of the rate-determining Zn(II)-OH nucleophilic attack on the substrate ester. Four distinct catalytic arrangements based on the stereochemistry of the tetrahedral intermediate and the nature of the oxyanion hole were considered (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Methods 4.1). These calculations provide the coordinates of the three Zn(II)-binding imidazole rings, the metal, and the transition state. Our previous RFdiffusion approach required the backbone coordinates and residue positions as inputs, which would require upfront sampling of the rotameric states and sequence position for each histidine. This cannot be done exhaustively: even with relatively coarse sampling around the side-chain chi angles χ1, χ2, and the backbone torsion angle ψ, there are on the order of 1018 possible choices for the side-chain conformations and sequence placements of our full catalytic site (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1). Whereas each RFdiffusion run has to be initialized with a specific (and generally randomly selected) choice from this enormous set of combinations, RFdiffusion2 as described above searches the entire space in each trajectory.

a, Hydrolysis of 4MU-PA yields phenylacetic acid and a fluorescent coumarin product. b, Example theozyme for Zn(II)-hydroxide nucleophilic attack on the 4MU-PA ester. Two-dimensional representation (left) and 3D DFT model (right). Arrows on the 3D model represent sampled conformational flexibility. c, Comparison of scaffold generation around an input theozyme using previous backbone centric RFdiffusion (top row) versus interaction functional group centric RFdiffusion2. RFdiffusion requires explicit upfront sampling of side-chain conformations and residue sequence positions, whereas RFdiffusion2 only requires the transition-state complex and the catalytic side-chain functional groups, implicitly sampling sequence space and rotameric space during inference. d, Snapshots of the global structure and active site from model XT during an RFdiffusion2 inference trajectory. The coordinates of the input transition-state complex and catalytic functional groups stay fixed during inference while the backbone structure, sequence positions, and unspecified atoms of the catalytic side chains are sampled by RFdiffusion2. The Cα atoms that host the catalytic histidines at the end of the trajectory are retrospectively highlighted as red spheres; these Cα atoms are not predetermined but rather move into the frame to host the fixed side chains as the global structure forms around the motifs.

RFdiffusion2 inference trajectories were used to build protein scaffolds housing the DFT-generated minimal active site configurations, referred to as theozymes2,33. Several snapshots from a representative trajectory are shown in Fig. 1d, transforming random noise on the left into the final backbone on the right (Supplementary Video 1). The Cα atoms of each residue (shown as coloured spheres representing final sequence position) are initially sampled from a Gaussian distribution, and the target functional atom positions (shown in sticks) stay fixed. As the trajectory proceeds from left to right, the global structure takes shape around the motif, with the fixed histidine side chains eventually connecting to Cα atoms of the protein backbone at sequence positions of the network’s choosing. A total of 5,120 RFdiffusion2 inference trajectories were carried out starting from different random seeds and for each of the resulting protein scaffolds, sequences were generated using ProteinMPNN34. The catalytic geometry and interactions with the transition state of those designs for which the AlphaFold235 predicted structure was close to the design model were further optimized using iterative LigandMPNN36 and constrained Rosetta repacking and minimization37 (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Methods 4.1). Designs containing a proposed general base positioned to activate the water molecule (that is, Glu, Asp or His within hydrogen bonding distance of the Zn(II)-bound water) and side-chain hydrogen bonds stabilizing the transition-state oxyanion (if applicable), and that AlphaFold2 predicted to adopt the target structure, were characterized with PLACER12 to assess active site preorganization. A total of 96 designs were selected for experimental characterization on the basis of predicted active site geometry and preorganization (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 2 and 3 and Supplementary Methods 4.1).

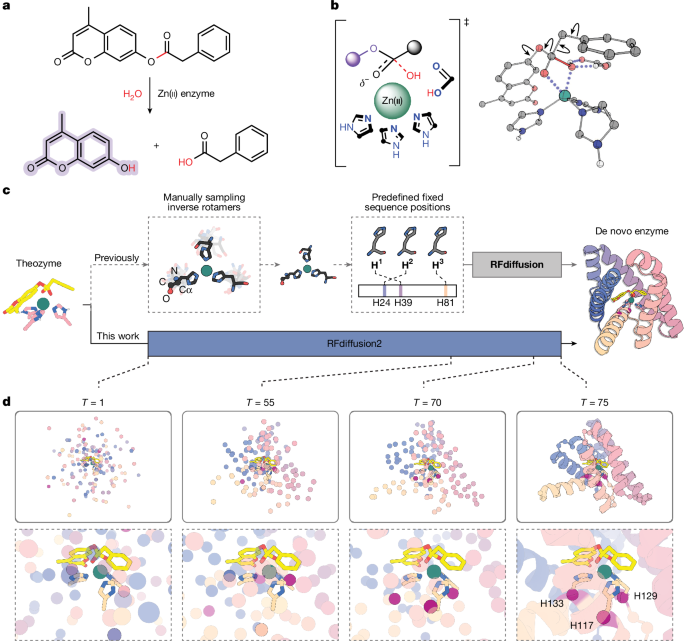

Linear DNA fragments encoding the 96 designs were cloned into a plasmid encoding a C-terminal Strep-tag and used to transform Escherichia coli, and the resulting proteins were purified using Strep-tag affinity chromatography. Eighty-six out of ninety-six designs were expressed and soluble as judged by SDS–PAGE analysis of the eluants (Supplementary Fig. 4). Purified designs were supplemented with zinc sulfate, and hydrolysis of 4MU-PA was monitored by fluorescence. Five designs (A1, A8, B9, C4 and F7) had activity well above background (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5). Sequence-verified single clones for each of these were expressed and purified by affinity chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography to obtain pure, monomeric protein fractions (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 and Supplementary Table 1). Michaelis–Menten kinetic characterization of the purified variants revealed a kcat/KM of 16,000 ± 2,000 M−1 s−1 for A1, the most active design, and kcat/KM values in the range of 35–140 M−1 s−1 for the other four designs (Fig. 2c,d, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Extended Data Table 1). For comparison, the kcat/KM of previously designed metallohydrolases24 ranged from 3 to 60 M−1 s−1 (Supplementary Table 2). A1 is also a relatively robust enzyme, and retains activity for at least 1,000 turnovers (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 8). A1 differs considerably from previously described proteins: the most similar structures identified through template modelling (TM) alignment with the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AFDB) have TM scores38 of 0.41 and 0.49, respectively, and do not have analogous arrangements of catalytic residues (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). We refer to A1 as zinc metalloesterase 1 (ZETA_1) throughout the remainder of the text.

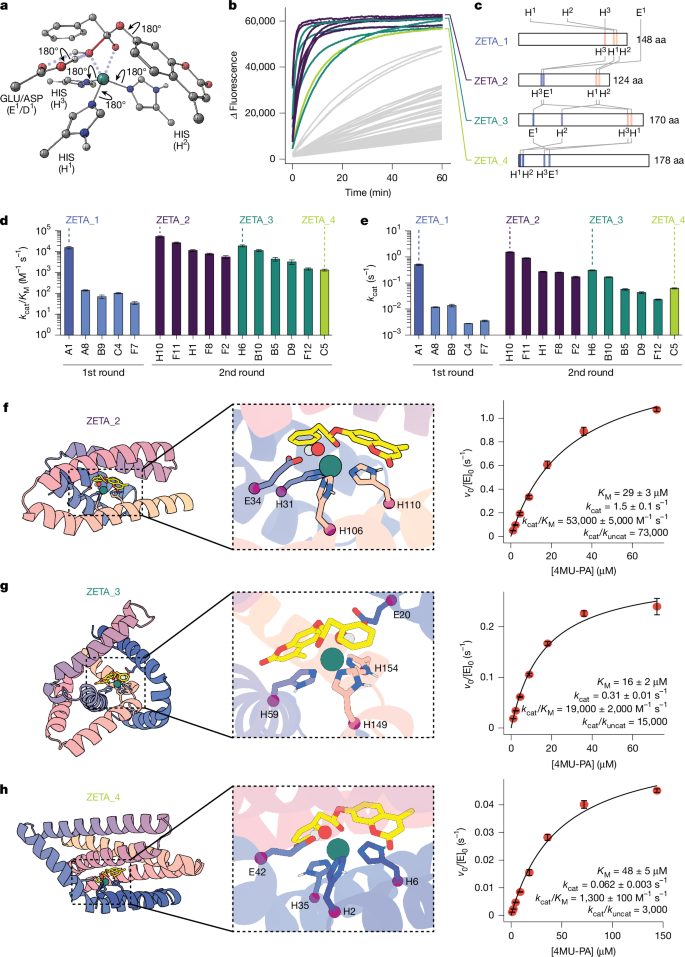

a, Design models of the most active designs. Sequence length (in amino acids (aa)) and the secondary structure harbouring each catalytic histidine are indicated below. b, Reaction progress curves. The dashed black line is the buffer background. c, Michaelis–Menten characterization of A1 (ZETA_1). The y axis shows the initial rate v0 divided by the total enzyme concentration ([E]0). d, Michaelis–Menten parameters of most active designs. e,f, Distribution of PLACER active site preorganization ensemble metrics for the ordered designs. Average design-prediction substrate r.m.s.d. (e) and average catalytic and binding residue design-prediction r.m.s.d. (f) across all predicted ensembles generated by PLACER for each design. g, For ZETA_1, the substrate position in PLACER ensembles is close to the design model, whereas in the inactive design H7, the substrate position fluctuates widely. h, For ZETA_1, the side chains surrounding the active site are largely fixed in positions close to the original design model, whereas in the inactive H8 design, the side-chain positions vary considerably. Note that only the first five randomly generated, unranked ensemble predictions are shown for PLACER in g,h. Data represent the mean ± s.d. of three independent measurements of initial velocity (c) and Michaelis–Menten parameters (d).

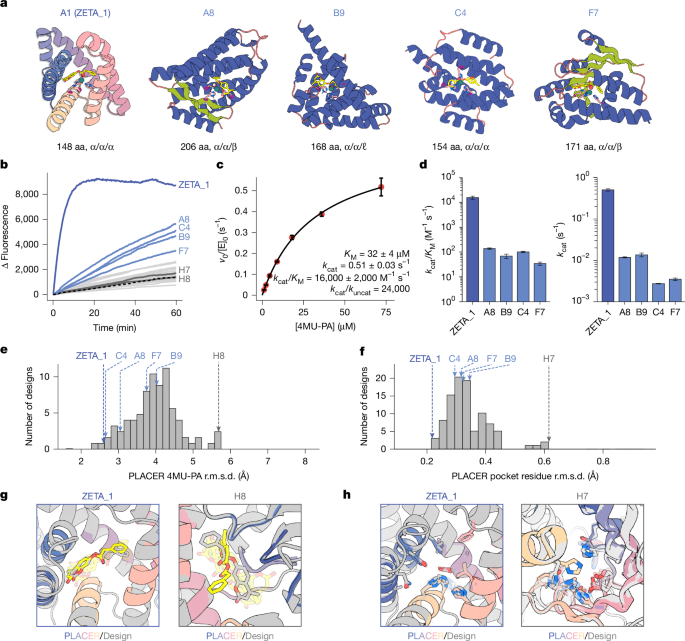

a, ZETA_1 design model (left) with close-up view of the active site showing the catalytic residues (middle) and a surface view of the designed pocket revealing high shape-complementarity to the substrate (right). b, Size-exclusion chromatogram of ZETA_1 showing a single peak corresponding to monomeric protein. c, Circular dichroism spectra of ZETA_1 recorded every 10 °C from 25 °C to 95 °C (viridis colour gradient), and after recooling to 25 °C (grey). The spectra suggest that ZETA_1 has an α-helical secondary structure and that it can refold after heating and partial unfolding. MRE, mean residue ellipticity. d, Circular dichroism signal at 222 nm measured every 1 °C and plotted as a function of temperature. e, [Product]:[enzyme] progress curve shows that ZETA_1 hydrolyses more than 1,000 4MU-PA molecules per enzyme. Note that the background reaction has been subtracted from the spectra so that every turnover can be attributed to the enzyme (Supplementary Fig. 8; further details in Supplementary Information, section 4.3). f, Reaction progress curves for the Zn(II) holo- and zinc-free apo ZETA_1 proteins showing zinc-dependent activity. Adding excess Zn(II) to the apo ZETA_1 sample after 30 min re-establishes the activity, demonstrating that zinc is essential for the catalytic mechanism of ZETA_1. WT, wild type. g, Zinc affinity of wild-type and mutant ZETA_1, measured as the dissociation constant (KD), where a lower value indicates tighter binding. h, Fluorescence progress curves comparing the activity of wild-type and mutant ZETA_1. i, kcat/KM for active ZETA_1 mutants compared with the wild type. Data represent the mean ± s.d. of three independent measurements of turnover number (e), fluorescence progress curves (f,h), Zn(II)-binding dissociation constant (g) and Michaelis–Menten parameters (i).

Design ZETA_1 not only has remarkably high activity but was also the top-ranked design in our in silico ranking. The structure in the absence of substrate was predicted to be very close to the design model by AlphaFold2 (Extended Data Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10), and the designed active site of ZETA_1 was predicted to be highly preorganized by PLACER, with the catalytic side chains fixed in place and the substrate held closely in its designed position, adjacent to the proposed Zn(II) site. PLACER12 is a deep neural network that, given a protein backbone containing a substrate, fully randomizes the positions of the substrate and all side chains within a 600-atom sphere, and then generates new coordinates for these groups12; repeated PLACER trajectories generate an ensemble of possible side-chain conformations and small molecule docks. Design ZETA_1 stood out from the other designs in both the extent of catalytic site preorganization (the catalytic side chains were largely fixed in space in catalytically competent conformations) and the positioning of the substrate–transition state in the active site (in the ZETA_1 ensemble, the substrate remained largely fixed in space in the active site, whereas in the inactive designs H7 and H8, it fluctuated considerably) (Fig. 2e–h and Supplementary Videos 2–5). Seven designs based on the same ZETA_1 backbone family were initially filtered out during the design selection phase, as they had suboptimal PLACER metrics; we retrospectively expressed and purified these designs and found that they had very low or no activity, further highlighting the utility of PLACER ensemble calculations for identifying active designs (Supplementary Fig. 11). These findings suggest that combining global structure prediction with detailed PLACER modelling of the active site provides a powerful approach to assessing the catalytic machinery and substrate binding geometry for design selection (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The ZETA_1 active site consists of a primarily hydrophobic pocket with three histidines binding Zn(II) with their Nε atoms, an aspartate as a potential general base, and an asparagine that forms a hydrogen bond to the coumarin ring (Fig. 3a). As in the original theozyme model used to generate ZETA_1, the Zn(II) ion also acts as an oxyanion hole, stabilizing the developing negative charge at the transition state; there are no nearby side-chain hydrogen bond donors (Extended Data Fig. 5). Zinc is absolutely critical for ZETA_1 activity: extraction of bound Zn(II) by dialysis in the presence of the chelator 1,10-phenanthroline completely eliminated activity, and activity was subsequently restored by addition of zinc to the solution (Fig. 3f). Zinc titration experiments measured a dissociation constant (KD) for Zn(II) of 41 ± 5 nM, which is similar to those of previous designed zinc enzymes26,39, but higher than native zinc hydrolases18,40,41,42, which typically have KD values less than 10 nM.

We carried out mutagenesis experiments to probe the contributions of the designed catalytic residues to Zn(II)-binding and catalysis (Fig. 3g–i and Supplementary Figs. 12–14). In the design model, N17 positions the substrate by hydrogen bonding with the lactone carbonyl of the coumarin moiety and could stabilize the developing negative charge on the leaving group; the N17A mutation led to a 8.1-fold decrease in kcat/KM (Supplementary Fig. 13). Mutation of all three metal-coordinating histidine residues to alanine simultaneously (H118A/H130A/H134A), as well as two of the three single histidine-to-alanine substitutions (H118A/H134A), completely inactivated the enzyme, as expected. Mutating the third Zn(II)-coordinating residue to alanine (H130A) resulted in a decrease of only 13-fold in kcat/KM, and mutation of the proposed general base D67 to alanine had little effect on kcat/KM and increased Zn(II)-binding affinity. These results suggest that H134/H118/H130 and H134/H118/D67 may be competing Zn(II)-binding sites owing to the close proximity of the coordinating side chains of H130 and D67, which was corroborated by Chai-1 (ref. 13) predictions of the protein–Zn(II)–substrate complex (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c); the D67A mutation may confine the zinc to the originally designed coordination sphere with the three histidines, which is more catalytically competent. In the H130A mutant, D67 is likely to coordinate Zn(II) and maintain binding, albeit in a less optimal binding geometry, lowering the zinc affinity and enzyme activity.

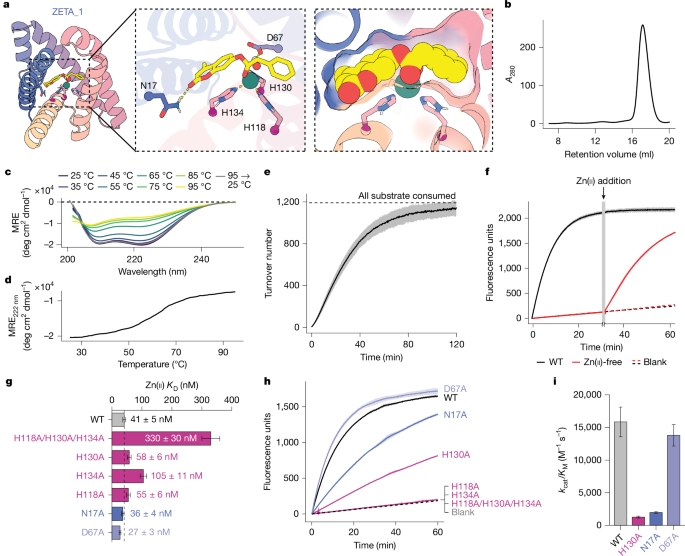

Guided by these observations, we started from new DFT theozymes explicitly containing the catalytic base, and generated protein structures scaffolding these theozymes using a newer version of RFdiffusion2 trained from random weight initialization on a threefold-larger dataset (previous versions were fine-tuned from structure prediction weights) (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Methods 4.2). Designs whose Chai-1 predictions of the protein–Zn(II)–substrate phosphonate ester complex, mimicking the reaction transition state, closely matched the design models with high confidence were identified by PLACER to have highly preorganized active sites (Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16). Ninety-six such designs spanning 37 RFdiffusion2-generated backbones were selected for experimental characterization (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Data 2 and 3). Eighty-five of the 96 designs were expressed and soluble (Supplementary Fig. 18), and 11 designs spanning 3 different folds had substantial zinc-dependent 4MU-PA hydrolysis activity (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Fig. 19). Michaelis–Menten analysis revealed that 5 designs had a kcat/KM greater than 104 M−1 s−1 and 6 designs had a kcat/KM greater than 103 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 6 and Extended Data Table 1). The most active designs for each backbone had a kcat/KM = 53,000 ± 5,000 M−1 s−1 (ZETA_2), kcat/KM = 19,000 ± 2,000 M−1 s−1 (ZETA_3), and kcat/KM = 1,100 ± 200 M−1 s−1 (ZETA_4) (Fig. 4f–h and Supplementary Fig. 20). ZETA_2 has a kcat = 1.5 ± 0.1 s−1, a threefold increase over the kcat of ZETA_1, and close to that of the metallohydrolase MID1sc10 obtained after 10 rounds of directed evolution24. RFdiffusion2 enables specification of the position of the substrate relative to the centre of mass of the designed protein; for ZETA_2 and ZETA_3, the protein was centred near the phenylacetate and 4-methylumbelliferyl moieties, respectively, of 4MU-PA, resulting in opposite substrate binding modes in the design models (that is, the 4-methylumbelliferyl is exposed in ZETA_2 and the phenylacetate is exposed in ZETA_3) (Extended Data Fig. 7).

a, Second round DFT theozymes containing the catalytic base. Zn(II) is coordinated by the His Nε atoms in these theozymes, and thus Cβ is explicitly modelled. b, Reaction progress curves coloured by scaffold family. c, Sequence length and catalytic residue positioning for the top design in each scaffold, named ZETA_2-4. These designs differ from each other and from ZETA_1. d,e, Steady-state kcat/KM and kcat parameters for the 11 second round hits, with colours corresponding to scaffolds using the scheme in b,c. Activities are higher, on average, than in the first round of designs (blue). f–h, Design model (left) with close-up view of the active site (middle) for ZETA_2 (f), ZETA_3 (g) and ZETA_4 (h). Right, Michaelis–Menten plots and parameters. Data represent the mean ± s.d. of three independent measurements of Michaelis–Menten parameters (d,e) and initial velocity (f–h).

The success rate in the second design campaign was considerably higher than the first campaign (11 out of 96 versus 1 out of 96 designs with kcat/KM greater than 103 M−1 s−1), supporting the conclusions from the first round analysis (Supplementary Figs. 21–26, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Discussion 2 and Supplementary Methods 4.2). Circular dichroism experiments confirmed that all active enzyme scaffolds from both design campaigns possess secondary structures consistent with their design models, indicating proper folding (Supplementary Fig. 21). The structures of ZETA_1-4 are rather different from each other and previously known metallohydrolases (Extended Data Fig. 4). The sequence positions of the catalytic residues in each of these enzymes are also very different, highlighting the diversity of RFdiffusion2 generated design solutions (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

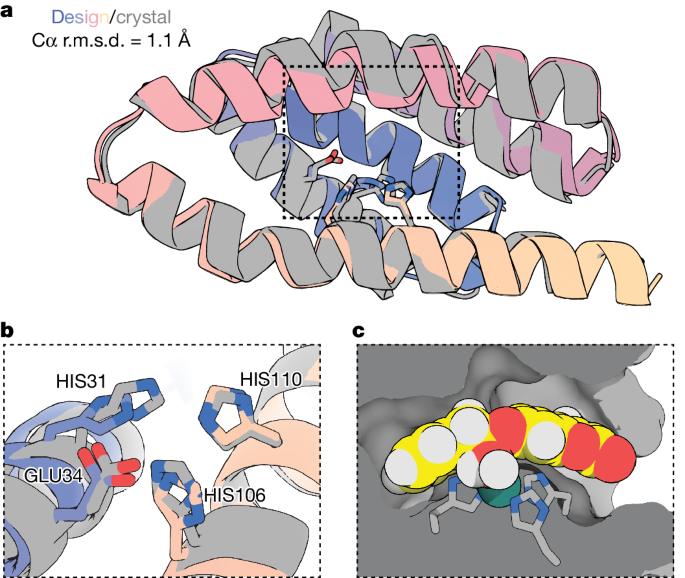

We determined the structure of ZETA_2, the most active design, in the apo state at 3.5 Å using X-ray crystallography (PDB: 9PYJ; Fig. 5). The experimental structure is in good agreement with the design model, with nearly superimposable backbones (Cα root mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) = 1.1 Å) and the catalytic residues preorganized in the designed geometry (Fig. 5a,b). The binding pocket is complementary to the superimposed transition state from the design model (Fig. 5c). We also solved a 2.1 Å structure after soaking ZETA_2 in Zn(II) (PDB: 9PYL; Extended Data Fig. 8); whereas the backbone was again nearly superimposable with the design model (Cα r.m.s.d. = 0.8 Å) and a Zn(II) ion was present with 100% occupancy at the designed location (r.m.s.d. = 1.7 Å), one of the Zn(II)-coordinating histidines (H110) was flipped out to interact with a Zn(II) ion bound at the surface of the protein, probably because of the high Zn(II) concentration in the crystal soaking buffer (250 mM) (Extended Data Fig. 8).

a, Cα superposition of the design model and the X-ray crystal structure of ZETA_2 (PDB: 9PYJ) in the apo state, resolved at 3.5 Å resolution. Catalytic residues are shown as sticks. The structures are in close agreement (Cα r.m.s.d. = 1.1 Å) and the catalytic residues in the experimental structure are preorganized close to their designed catalytic geometry. b,c, Magnification of the active site of ZETA_2, highlighting the agreement between the experimental and designed catalytic geometry (b) and the shape-complementarity of the designed binding pocket and the transition state model (superimposed in from the design model) (c). The crystal structure is shown in grey and the design model is in colour in all panels.