When US technology entrepreneur Peter Thiel’s book Zero to One was published in Chinese in 2015, it struck at an insecurity felt by many in China. Thiel suggested that although the country excelled at scaling and commercializing emerging technologies, it lagged behind the United States in true innovation — creating something entirely original from scratch. Take the iPhone: engineers in Cupertino, California, design them; workers in -Shenzhen, China, build them.

For more than a decade, Chinese policymakers have aimed to shed this image, embedding the pursuit of innovation into national industrial policies, such as Made in China 2025. And there are some early results to show. For instance, in 2023, the Shenzhen-based technology company Huawei launched the Mate 60 smartphone, which is powered by a domestically produced chip. This was celebrated as a symbolic breakthrough — demonstrating that China could manufacture advanced semiconductors despite stringent US sanctions on crucial tools and high-end design software. And last month’s release of Deepseek-R1, a Chinese large language model developed at a fraction of the cost of its Western counterparts, sent shockwaves through the US tech establishment.

Prominent venture capitalist Marc Andreessen described it as “AI’s Sputnik moment” — a reference to the mid-twentieth-century US–Soviet space race that began with the launch of the first satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union. Accessing Deepseek through an application programming interface (API) — a protocol for connecting software applications — is roughly 13 times cheaper than similar models developed by OpenAI, based in San Francisco, California.

The sudden rise of Deepseek has put the spotlight on China’s wider artificial intelligence (AI) ecosystem, which operates differently from Silicon Valley. Although consumer-facing applications garner much attention, Chinese AI firms, unlike their US counterparts, are in fact more invested in solving industrial and manufacturing problems at scale. The divergence in priorities reflects the forces driving innovation in each economy: venture capital in the United States and large-scale manufacturing enterprises and organs of the state in China.

Technology split

At the root of the difference is China’s comparative advantage in the world economy — manufacturing — along with the government being the largest client for new technologies. The Chinese government aims to develop low-cost, scalable AI applications that can modernize the rapidly developing country.

At a press conference last September, for example, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian laid out the view of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that tech innovation is a core component of “national development”. To stay in the good books of Beijing, AI research laboratories have responded by building practical applications — to make trains run on time, monitor fish stocks and provide automated telehealth services.

Beijing-based company Zhipu AI has partnered with several local governments and state-owned enterprises to deploy its agent model, which automates tasks such as form-filling and financial-report analysis. Last month, tech behemoth Alibaba, headquartered in Hangzhou, China, reached a deal with the Beijing-based startup 01.AI to set up an ‘industrial large model laboratory’ focused on deploying AI to optimize business and industrial processes.

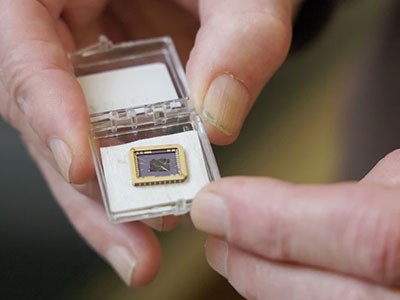

Nvidia is a US company that manufactures chips needed to build AI systems.Credit: Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty

AI also has an interesting role in China’s energy transition, from large-scale trials of integrated smart homes to the roll-out of a major investment (equivalent to US$800 billion) for a national smart grid.

Thus, Beijing’s goal is not necessarily to attain global leadership in AI chatbots, but to use the underlying technology to develop affordable, commercially viable business solutions. Its applications can then be exported, especially to lower-income countries. In other words, China’s target is not necessarily ‘frontier AI’, but ‘mass-market AI’. Its emerging AI playbook mirrors its approach to other technologies, such as electric vehicles and clean energy: not the first to innovate, but the first to make them affordable for widespread use.

Out of necessity

The technological ‘stack’, an interconnected set of resources needed to develop advanced AI models, includes hardware, such as semiconductors; cutting-edge learning algorithms optimized for that hardware; and a backend comprising energy-intensive data centres and predictable capital flows.

To maintain its global lead in AI technology, the United States has periodically imposed export sanctions on key components. On 7 October 2022, the administration of former US president Joe Biden released a set of export controls on advanced computing and semiconductor-manufacturing items, aiming to block China from purchasing high-performance chips from companies such as Nvidia, based in Santa Clara, California. Then–national-security-adviser Jake Sullivan called it the “small yard, high fence” strategy: the United States would erect a ‘fence’ around crucial AI technologies, encouraging even companies in allied countries, such as the Netherlands and South Korea, to restrict shipments to China.

China–US research collaborations are in decline — this is bad news for everyone

Meanwhile, the CCP sees moving up the manufacturing supply chain, particularly into categories such as airplanes and semiconductors, as crucial for sustained economic growth. In that sense, the rivalry adds urgency and intensity to China’s efforts. If the United States owns the technology of the future and is willing to use export controls, then China runs the risk of economic stagnation — and the political turbulence that might accompany it. The battle for supremacy over AI is part of this larger geopolitical matrix.

And China has been preparing for this scenario for a while. In 2019, the US added Huawei to its entity list, a trade-restriction list published by the Department of Commerce. This spurred China to rethink how to become less vulnerable to US export controls. The Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE) created a set of integrated research platforms (IRPs), a major institutional overhaul to help the country to catch up in key areas, including robotics, driverless cars and AI, that are vulnerable to US sanctions or export controls. There are now 30 IRPs.

Take the IRP for new-generation integrated circuit technology at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, for instance — the sort of state-driven research enterprise that could drive breakthroughs. The 2022 export restrictions targeted chips with ‘nodes’ — the smallest component on a semiconductor — of 14 nanometres or less. Chips with smaller nodes can pack more transistors into the same area, potentially improving performance and efficiency. In 2021, the Fudan IRP was ahead of the curve, and already recruiting for roles to support research on even smaller nodes, of 3–4 nanometres. These high-performance chips now fuel the AI tech stack. To address manufacturing bottlenecks, the third round of China’s ‘Big Fund’ — a state-backed investment initiative to pool in resources from -public enterprises and local governments — was announced last year, with a planned US$47 billion investment in its semiconductor ecosystem.

This shows that China is serious about indigenizing AI capabilities by investing significant institutional, academic and scientific resources. By restricting access to chips, US policy has forced China to explore workarounds and unconventional methods. Many of these endeavours might fail. But it doesn’t take many successes to make a global impact.

The IRPs have emerged as ideal platforms to train a cadre of engineers, filling a talent gap that existed even a decade ago. The Deepseek success story is, in part, a reflection of this years-long investment.