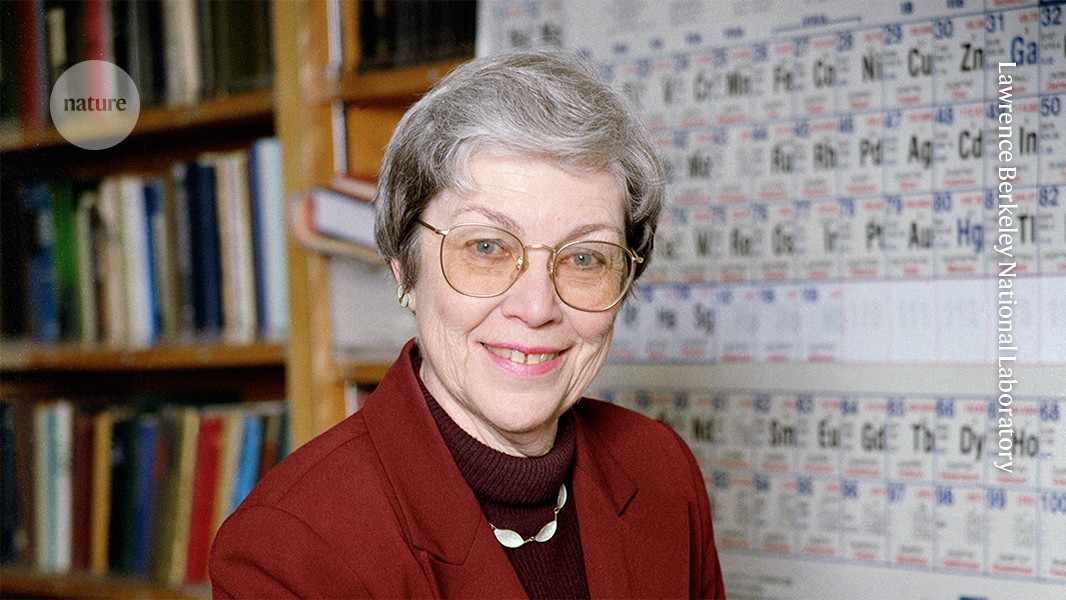

Credit: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Darleane Hoffman was a trailblazing nuclear chemist whose work helped to extend the periodic table and deepen our understanding of the heaviest elements. The transuranic elements — those with an atomic number higher than uranium’s 92 — are all unstable and radioactive. Her discovery of naturally occurring plutonium-244 overturned the long-held premise that uranium-238 was the heaviest element found in nature. Her research influenced our understanding of nuclear fission, advanced cancer therapies and improved nuclear-waste-management protocols. She has died aged 98.

One of her proudest achievements was validating the discovery of element 106, later named seaborgium in honour of her friend and mentor, Glenn Seaborg. Beyond her landmark discoveries, Hoffman will also be remembered for her advocacy for women in science.

Physicists unleashed the power of the atom — but to what end?

Born in Terril, Iowa, Hoffman developed an early fascination with science — encouraged by her father, a school principal who taught mathematics. She began studying applied art at Iowa State College in Ames, but switched to chemistry, inspired by her teacher Nellie Naylor and physicist Marie Curie, who attained global renown for her work on radioactivity. Hoffman was drawn to nuclear chemistry and the excitement of a field still in its infancy. Later, she would tell her students that she was often the only woman in her university chemistry classes.

After earning her doctorate in nuclear chemistry in 1951, Hoffman began her career at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, before joining the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, where she became the first female division leader in 1979. Her husband Marvin Hoffman, a nuclear physicist, had been a fellow graduate student and collaborated in her early research. She detected plutonium-244 in 1971 while analysing rock samples from California’s Mountain Pass mine. Before this discovery, scientists thought that all elements heavier than uranium had to be created artificially in particle accelerators.

The spy who flunked it: Kurt Gödel’s forgotten part in the atom-bomb story

Hoffman further advanced the field by isolating fermium-257 and showing that it could split into two fragments of similar size — an unexpected result at the time, because fission was thought to produce uneven fragments. Her findings, initially met with scepticism, forced scientists to rethink how fission works.