Bioinformatic analysis of known AMPs

All the computational analyses presented were done using Python v.3.11 or R v.4.3.1. Python packages used: beautifulsoup4 v.4.12.2, bio v.1.6.2, GSEApy v.1.1.0, matplotlib v.3.7.1, NumPy v.1.24.3, pandas v.2.0.2, SciPy v.1.10.1, seaborn v.0.12.2, sklearn v.0.0.post5, urllib3 v.2.0.3. R libraries used: BiocManager v.1.30.22, circlize v.0.4.15, ComplexHeatmap v.2.16.0, drawProteins v.1.20.0, dplyr v.1.1.2, ggplot2 v.3.4.4, ggnewscale v.0.4.10, ggrepel v.0.9.4, PerformanceAnalytics v.2.0.4, RColorBrewer v.1.1-3, stringr v.1.5.1, tidyr v.1.3.0, tidyverse v.2.0.0, ggplot2 v.3.4.4.

Data retrieval and collection of experimentally validated AMPs

AMP sequences were retrieved from four publicly available databases: CAMP(R4)60, DRAMP61, DBAASP62 and dbAMP63. For each database, AMP sequences were downloaded along with associated metadata, including but not limited to protein ID, sequence, organism source and activity. Following data retrieval, we filtered for peptides from naturally occurring sources, excluding synthetic or engineered peptides.

BLAST analysis

The combined dataset of AMPs underwent sequence similarity analysis using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)64 v.2.2.26. This analysis was conducted against the human proteome database obtained from Swiss-Prot (September 2023).

Peptides with sequence identities matching human proteins completely were identified and subsequently retained for further analysis. To ensure stringent criteria, peptides shorter than five amino acids were excluded from the dataset to maintain consistency and reliability in subsequent analyses.

The analysis revealed AMPs that had not been previously associated with human sources but have now been authenticated as constituents of the human proteome (Supplementary Table 1).

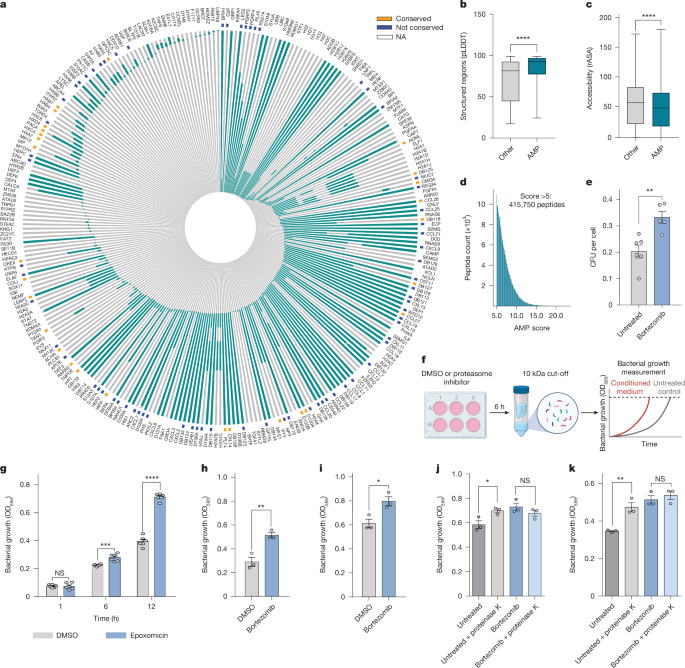

Conservation analysis

For AMP conservation analysis, we used orthogroups of the Euarchontoglires subclade, which include orthologues for Homo sapiens. We used this approach, which is solely based on proteins with clearly defined orthogroups in the EggNog database65 as it is stricter in terms of conservation compared with simple sequence homology-based protein alignment. In short, for each protein containing a peptide that was designated as a putative AMP, on the basis of 100% identity to a previously published AMP, we calculated the amino acid conservation rate by Rate4Site66. Proteins lacking clearly defined orthologues were excluded from the analysis (these proteins are marked NA). To estimate the AMP sequence conservation, we compared the conservation rate, per amino acid residue, in the AMP sequence or from the same protein outside that region, using a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction was used to control for multiple hypotheses testing.

AMP accessibility analysis

To analyse the position of known AMPs in the structures of mature proteins, we used AlphaFold-predicted monomeric structures67 from the human proteome (uploaded 14 January 2024). For each protein that includes a known AMP sequence in its polypeptide chain, we calculated a relative solvent-accessible surface area (rASA) using the FreeSASA library68. The predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) of amino acids from AlphaFold69 was used to measure residue-wise disorderness (the more disordered region, the smaller the pLDDT score)70. To demonstrate the general trends for amino acids in AMP, we compared the rASA and pLDDT of amino acids inside and outside of the AMP regions for the whole set of AMP-containing proteins using a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test. To visualize AMP in the host protein, we used PyMOL v.2.5.7.

Analysis of AMP gene expression in different tissues

RNA-sequencing data for human tissues (RNA HPA tissue gene data) were obtained from the Human Proteome Atlas website71. We identified genes that encode known AMPs present in the human genome. These genes were then cross-referenced with the transcriptomic data obtained from the Human Proteome Atlas dataset to assess their expression profiles across different tissues. The transcript abundance for each AMP gene was determined on the basis of protein transcripts per million values. The data were normalized per gene by a z-score.

Enrichment analysis using KEGG pathways

We performed an enrichment analysis using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway database72 2021 version and GO Molecular Function73 2023 version. To execute this analysis, we used the GSEAPY Python package v.0.10.5. We compared the proportion of genes associated with the identified pathways to the entire gene repertoire catalogued in Swiss-Prot (September 2023).

Bioinformatic analysis of potential proteasome-derived AMPs in the human degradome

The PDDP sequence list was assembled from multiple MAPP12 experiments conducted in the laboratory (Supplementary Table 3). Subsequently, this dataset was filtered using scoring criteria derived from MaxQuant analysis, retaining only peptides that passed a threshold of 1% false discovery rate. After filtering, all peptides in the dataset were subjected to a previously proposed scoring algorithm26, as implemented previously74.

In silico proteasome cleavage of the human proteome

To identify potential proteasomal cleavage sites in protein sequences, we used the pepsickle algorithm on the human proteome (Swiss-Prot, September 2023)75. The results obtained from pepsickle were used to generate peptide combinations ranging from 10 to 50 amino acids in length, which represent putative proteasome-generated peptides. The identified peptides were cross-referenced with previously reported AMPs to ascertain their potential efficacy. Mean scores were computed for peptides present in the known datasets to choose the minimal AMP score as a threshold for PDDPs (excluding a score of zero). Peptides scoring above the threshold of five, representing the mean score of reported AMPs, were considered as putative PDDPs (415,750 peptides). For overlapping peptides, only the top-scoring peptide was included. Additional filtering for cationic carboxy termini was added, yielding 270,872 peptides.

Proteasome-derived peptides in biological fluids

To identify proteasome-derived peptides in biological fluids we used peptidomics data from blood, wound fluid, endometrium fluid, milk and urine, and compared them with the sequences of proteasome-derived peptides76,77,78,79,80.

Human cell lines

Human cell lines used in this study were HCT116 (CCL-247), A549 (CCL-185), MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26) and CaCo-2 (HTB-37) obtained from ATCC. A549 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; 41965039; Gibco) and HCT116 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5 A Medium (M8403; Sigma). MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (F7524; Sigma), sodium pyruvate (03-042; Sartorius) and glutamine (03-020; Sartorius). Cells were cultured and passed in accordance with standard procedures at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The absence of mycoplasma contamination was verified monthly.

Bacterial strains

Pseudomonas aeruginosa CHA-OST, P. aeruginosa PAO1, E. coli K12 MG1655, M. luteus NCTC 2665, S. haemolyticus JCSC1435, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica, S. typhimurium SL1344 and S. typhimurium SL1344 RFP were provided by the R. Straussman, E. Elinav and R. Avraham laboratories (Weizmann Institute of Science). All bacteria were cultured in LB (Sigma) according to standard procedures. Aliquots of the bacteria were cultured from frozen stocks in fresh LB overnight and diluted to the desired cell density for each assay. The OD600 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer and correlated with the CFU counts after serial dilution plating on LB agar.

Peptide synthesis

To assess the antibacterial activity of selected MAPP-derived peptides, which were predicted to have antibacterial activity, we used chemically synthesized peptides with the same amino acid sequences (GenScript). The sequences of peptides used in this study are presented in Supplementary Table 7.

LK20 was synthesized as previously described and used as a positive control81.

Assessment of the minimal inhibitory concentration

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was assessed as previously described with some adjustments30. In brief, an overnight culture of bacteria was diluted 1:50 in 5 ml fresh LB medium and allowed to grow in a shaking incubator (200 rpm) at 37 °C until an OD of 0.1 (595 nm) was reached. Peptides were diluted to a concentration of 400 µg ml–1 in a 96-well plate and then serially diluted twofold. Bacteria were then introduced to the peptides resulting in a final volume of 200 μl of LB with a bacterial load of 5 × 105 CFU ml–1 (for M. luteus 5 × 104 CFU ml–1) containing <1% DMSO (Sigma). The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Growth was determined by measuring the OD at 595 nm using a plate reader.

Assessment of minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The MBC was performed as previously described with some adjustments82. In brief, the bacterial culture was prepared as described above and washed three times with PBS (Sartorius). Peptides were diluted to a concentration of 256 μg ml–1 in a 96-well plate and then serially diluted twofold. Bacteria were then introduced to the AMPs resulting in a final volume of 200 μl of PBS with a bacterial load of 5 × 105 CFU ml–1 containing <0.5% DMSO. The plate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Each treatment was serially diluted tenfold in PBS and spot-plated three times in LB agar plates. The log-transformed reduction was calculated using the CFU count.

Synergistic antibacterial activity of PDDPs

The synergistic activity of the PDDPs was assessed as previously described83 with lower concentrations. The combinations of five (PPP1CB, DFNA5, DCTN4, PSMG2, CHMP2A) derived peptides and ten peptides were prepared by combining the peptides in equal concentrations to create mixed peptide stocks. Each stock was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg ml–1 in DMSO, with individual peptide concentrations of 2 mg ml–1 for the five-peptide mixture and 1 mg ml–1 for the ten-peptide mixture. The antimicrobial activity of these peptide mixtures was evaluated using bacterial killing assays as previously described. The fractional bactericidal concentration (FBC) was calculated for peptide X according to Equation 1:

$${\rm{FBC}}({\rm{PDDP}}\;{X})=({\rm{concentration}}\;{\rm{of}}\;{\rm{PDDP}}\;{X}\;{\rm{in}}\;{\rm{combination}})/({\rm{MBC}}\;{\rm{of}}\;{\rm{PDDP}}\;{X}\;{\rm{alone}})$$

(1)

The synergistic antibacterial activity was determined by the FBCI, which was calculated according to Equation 2:

$${\rm{FBCI}}({\rm{MIX}})=\Sigma ({{\rm{FBC}}}_{{\rm{s}}})={{\rm{FBC}}}_{1}+{{\rm{FBC}}}_{2}+{{\rm{FBC}}}_{3}+\ldots +{{\rm{FBC}}}_{10}$$

(2)

FBCI values were defined as synergy for FBCI < 0.5, additive for 0.5 < FBCI ≤ 1, indifference for 1 < FBCI ≤ 4 and antagonistic for FBCI > 4. For FBC calculations, peptides that did not show bactericidal activity at the highest tested concentration (128 μg ml–1), were assigned a value of 256 μg ml–1, following the approach described previously84.

Membrane permeabilization assay

To measure the effect of putative AMPs on the viability and permeabilization of bacterial strains and human cell lines (A549 and HCT116), we used a propidium iodide (PI; Sigma) assay85. Bacteria were grown to mid-logarithmic phase, washed and diluted with assay buffer (10 mM MES pH 5.5, 25 mM NaCl; Sigma) to a concentration of 5 × 108 cells ml–1 and mixed with PI to a final concentration of 5.5 μg ml–1 (8.3 μM). Next, 100 μl of bacteria with PI were transferred to 96-well plates and mixed with putative AMPs in various concentrations and with negative (DMSO) and positive (0.1% SDS; Bio-Lab) controls. Then the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a fluorescence reader and the output signals (excitation, 535 nm; emission, 617 nm) were measured every 5 min. Bacterial permeabilization activity was normalized against the maximum fluorescence output from the positive control. For human cell lines, cells were collected and washed two times in PBS then suspended in PBS containing PI 5.5 μg ml–1 (8.3 μM) and the fluorescent signal was measured.

Transmission electron microscopy

We used transmission electron microscopy to directly assess the membrane disruption by PDDPs. Bacteria were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase, incubated with the putative PDDPs for 30 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde (EMS) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (Sigma) containing 5 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4), postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (EMS) supplemented with 0.5% potassium hexacyanoferrate trihydrate and potassium dichromate (BDH Chemicals) in 0.1 M cacodylate for 1 h, stained with 2% uranyl acetate (EMS) in double distilled water for 1 h, dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions and embedded in epoxy resin (Agar Scientific). Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were obtained with a Leica EMUC7 ultramicrotome and transferred to 200 mesh copper transmission electron microscopy grids (SPI). Grids were stained with lead citrate and examined with a Tecnai T12 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Digital electron micrographs were acquired with a bottom-mounted TVIPS TemCam-XF416 4k × 4k CMOS camera.

Bacterial growth in conditioned medium

Bacterial growth in a conditioned medium collected from cells was performed as described previously86. A549 or HCT116 cells were cultured until 90% confluence in standard medium without antibiotics. Cells were washed three times in PBS and the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM and incubated for 6 h. Conditioned medium was filtered (10 kDa cut-off; PES; 964014, Analytical Sales and Services, or Vivaspin, VS0202). Then, 100 μl of the filtered conditioned medium were mixed with the bacteria pre-diluted in DMEM to obtain the final bacterial concentration of approximately 5 × 107 bacteria per ml (for M. luteus approximately 5 × 106 CFU per ml). Bacterial growth was measured in the plate reader at OD at 595 nm every 10 min with shaking.

For proteasome-inhibition experiments, cells were treated for 6 h with bortezomib (50 nM) and stimulated with bacterial TLR agonists: heat-killed Listeria monocytogenes (TLR2) 108 cells per ml, LPS-EK (TLR4) 500 ng ml–1, FLA-ST (TLR5) 1 μg ml–1, ATP 5 mM and heat-killed (95 °C, 15 min) bacteria. For inhibition of the proteasomal β2 subunit, cells were incubated for 6 h with leupeptin (20 µM).

Intracellular infection assay (CFU count)

Salmonella typhimurium or M. luteus was used for intracellular infection in which the ability of bacteria to infect the human cell lines was estimated. An overnight culture of bacteria was grown to the mid-logarithmic phase in fresh LB medium with 0.3 M NaCl. Bacteria were washed three times with PBS and added to A549 cells at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 100 for S. typhimurium and MOI of 10 for M. luteus (unless specified otherwise). Then, cells were incubated with bacteria for 1 h, washed twice with PBS and incubated for 1 h in DMEM with 100 μg ml–1 gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) solution for 15 min. Then, cell lysates containing bacteria were plated on LB agar in serial dilution to determine the CFU count.

Intracellular infection assay (fluorescence assay)

Overnight cultures of S. typhimurium SL1344 RFP were diluted and grown to the mid-logarithmic phase in fresh LB medium with 0.3 M NaCl. Then the bacteria were washed three times with PBS and added to A549 cells with MOI of 5. After 1 h of bacterial infection, cells were washed three times and incubated for 1 h in DMEM with 100 mg ml–1 gentamicin. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA (Sigma) solution for 15 min. Then, cells were treated with DAPI (Sigma, 2.5 µg ml–1) for 2 min for nuclear staining and the plate was stored in PBS with 100 mg ml–1 gentamicin until imaging. Cells were imaged using a wide-field Leica DMi8 microscope with a 20× air objective (NA = 0.80). Analysis was done by ImageJ v.2.14.0/1.54f JAVA v.1.8.0_322.

Targeted protein degradation assay (dTAG system)

PPP1CB and eGFP were cloned from pEGFP(N3)-PP1beta, a gift from A. Lamond and L. Trinkle-Mulcahy87 (plasmid 44223, Addgene), into the N-terminal dTAG plasmid pLEX_305-N-dTAG, a gift from J. Bradner and B. Nabet37 (plasmid 91797, Addgene). The plasmids were cut by restriction enzymes ClaI and AgeI followed by ligation with a T4 ligation enzyme (NEB). PSMG2 cloning into pLEX_305-N-dTAG was ordered from GenScript. Stable cell lines were generated using third-generation lentiviral infection. Cells were treated with 500 nM of the dTAGV-1 compound (Tocris 6914) for 6 h for conditioned medium experiments. For intracellular bacterial infection, cells were incubated for 1 h before infection. DMSO was used as a control. The degradation of the proteins by the dTAG system was assessed by western blot using the anti-HA-tag antibody (SAB2702196; Sigma) and anti-vinculin antibody as a loading control (ab129002; Abcam). Bacterial growth was assessed in the collected medium and by intracellular cell infection.

PSME3 and PPP1CB knockdown

To assess the role of PSME3 (also known as PA28γ) in generating proteasome-derived antibacterial peptides, MISSION short hairpin RNAs were used to target PSME3 expression (Sigma; TRCN0000290025). We generated an A549 cell line stably expressing the plasmid under selection (with puromycin 2 μg ml–1). To examine the effect of PPP1CB knockdown on bacterial growth in a conditioned medium, we similarly generated A549 cells stably expressing the MISSION short hairpin RNAs targeting PPP1CB from Sigma (TRCN0000338386). RFP knockdown was used as a control (TRCN000002209).

Bacterial infection of PSME3 knockdown and NF-κB inhibition

To examine the antimicrobial response by PSME3 and the dependence on the NF-κB activation response during infection, stable A549 cells expressing shCTRL or shPSME3 were treated with JSH-23 (40 µM) or IKK16 (1 µM) for 2 h, followed by infection with S. typhimurium SL1344. We analysed the response using CFU counts or a fluorescence assay as described above.

Dynamic measurements of transepithelial–transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) assays

TEER assay88 was conducted on CaCo-2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma cell) monolayers. CaCo-2 cells were seeded onto a 96-well ‘impedance’ plate (Axion BioSystems; Z96-IMP-96B-25) and monitored using the Maestro Edge platform (Axion BioSystems) until they reached full confluence, exhibiting a resistance range of 800–1,200 Ω. The evaluation of barrier integrity was carried out through the Axion ‘Impedance’ module, using the ratio of cellular resistance at a low frequency (1 kHz) to that at a high frequency (41 kHz). In coculture experiments, P. aeruginosa (105) bacteria were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min, resuspended in 4.4 ml of cell culture medium (DMEM-F12) supplemented 2 mM l-glutamine without antibiotics or sera, then serially diluted with PPP1CB. A final volume of 200 μl of the diluted bacterial suspension was added to each well. The barrier index was monitored at a high temporal resolution of 5 min over 6 h, normalized to the reference time (t = 0). An additional correction was applied by normalizing the barrier index to that of unstimulated cells (CaCo-2).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mouse models of bacteraemia and pneumonia

Bacterial cultures and growth conditions

The wild-type P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was provided by M. Vasil as previously published89,90,91. Aliquots of the bacteria were cultured from frozen stocks in fresh LB overnight and diluted to the desired cell density for each assay. The OD at 600 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer and correlated with the numbers of CFU after serial dilution plating on LB agar.

Ethical statement

Animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal protocol was thoroughly reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, under protocol no. 22051. Male and female 6-week-old mice, with a body weight in the range of 27–35 g (male) or 22–30 g female) (both sexes in the same group), were purchased from Charles River. At arrival, all mice were randomly housed by animal care technicians who were not part of the study team. Mice were acclimatized for one week before experimentation. All mice were housed in positively ventilated microisolator cages with automatic recirculating water located in a room with laminar, high-efficiency particulate-filtered air, with full access to autoclaved food, water and bedding. The animal room operates on an alternating 12-h light–dark cycle, with the ambient temperature set to 68 °C (range 67–71 °C) and humidity at 28% (range 17–59%). At the completion of experiments, mice were euthanized by overdosing with CO2 or ketamine–xylazine, followed by cervical dislocation.

Mouse models of acute pneumonia and bacteraemia

For the acute pneumonia model92, CD-1 mice (n = 8 per group) were intranasally inoculated with the indicated concentration of the P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 as previously published93,94,95. Infected mice were treated twice daily with 5 mg kg–1 of PPP1CB i.v. Lungs were collected and processed 48 h post-infection (hpi). For the bacteraemia model, CD-1 mice (n = 8 per group) were intraperitoneally infected with the P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (2.5 × 107 CFU per mouse)93,95. Infected mice were treated twice daily with 10 mg kg–1 of PPP1CB i.v. and spleens were analysed at 24 hpi. The control group, in both mouse models, was treated with the same volume of sterile PBS or the antibiotic tobramycin (50 mg kg–1, i.p., once daily). Mouse tissues were homogenized in 1 ml sterile PBS using an Omni Soft Tissue Tip Homogenizer (Genizer). Bacterial burden was determined through serial dilution plating of the homogenate onto LB agar plates. For the mouse model of mortality because of bacteraemia-induced sepsis, male and female 7-week-old mice (15 per cohort) were anaesthetized by isoflurane and intraperitoneally inoculated with a high dose of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (6.7 × 107 CFU per mouse, in 100 µl), which resulted in mortality because of bacteraemia-derived sepsis as previously described95. Infected mice were treated twice daily retro-orbitally beginning at 2 hpi, for 3 days with PPP1CB i.v. (10 mg kg–1, in 50 μl). The antibiotic tobramycin (10 mg kg–1, in 50 μl) and the same volume of vehicle (sterile PBS once daily, in 50 μl) were used as both positive and negative controls. Mouse mortality was monitored for 6 days (120 h). Survival analysis was performed with a Kaplan–Meier log rank survival test using GraphPad Prism (v.9.0.2). All collected mouse tissues were submitted for H&E and Gram staining and the pathological scoring was done manually. The degree of lesions was graded from one to five on the basis of severity: 1, not present or minimal (<1%); 2, slight (1–25%); 3, moderate (26–50%); 4, moderate–severe (51–75%); 5, severe–high (76–100%).

Immunoblotting

Protein concentrations were determined using the BC Assay Protein Quantitation Kit (Interchim). In brief, 20 μg of total protein was separated by SDS–PAGE using 4–20% gradient Criterion TGX protein gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using an iBlot 2 Gel Transfer Device (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The membranes were blocked in 5% milk prepared in TBS–0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma) and incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by washing and incubation with secondary antibody. Blots were developed using the ChemiDoc XRS+ Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

MAPP and proteomics of infected cells

A549 cells were seeded and cultured until 90% confluency, at which point they were washed twice with PBS. The cells were then incubated in serum-free DMEM and infected with S. enterica at a MOI of 5 for either 1 or 4 h. Uninfected cells served as controls. Cells were collected and analysed by MAPP.

MAPP analysis of cells treated with proteasome inhibitors

MDA-MB231 cells were seeded and cultured until 90% confluency, at which point they were washed twice with PBS. Cells were treated with DMSO, bortezomib (50 nM) or the immunoproteasome inhibitor ONX-0914 (1 μM) for 6 h, then washed and collected for further processing by MAPP as previously described.

Proteasome immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed with 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP and 1:400 protease-inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem), homogenized through freeze–thaw cycles and passed through a needle (25G). The lysates were cleared by 30-min centrifugation at 21,130g at 4 °C. Pellets were lysed again with 0.5 mM ammonium persulfate to enrich the nuclear fraction then centrifuged. Mixed lysates were cross-linked as previously described12. For immunoprecipitation, the lysates were then incubated with Protein G–Sepharose beads (Santa Cruz) with antibodies against PSMA1 and eluted with 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 8 M urea and 50 mM DTT for 30 min at 37 °C. Eluted fractions were analysed by SDS–PAGE to evaluate yield and purity.

Isolation of proteasome-cleaved peptides

Immunoprecipitated proteasomes and their associated peptides were loaded on C18 cartridges (Waters) that were prewashed with 80% acetonitrile (ACN) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) followed by washing with 0.1% TFA only. After loading, the cartridges were washed with 0.1% TFA. Peptides were eluted with 30% ACN in 0.1% TFA.

Assessing the proteasome composition

After immunoprecipitation, proteasomes were denatured by 8 M urea for 30 min at room temperature, reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma) for 1 h at 25 °C and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma) in the dark for 45 min at 25 °C. Samples were diluted to 2 M urea with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Proteins were then digested with trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37 °C at 50:1 protein:trypsin ratio, followed by a second trypsin digestion for 4 h. The digestions were stopped by adding TFA (1% final concentration). Then, peptides were desalted using Oasis HLB, μElution format (Waters). The samples were vacuum dried and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

Proteomic analysis by liquid chromatography (LC)–MS

Lysates in 5% SDS in 50 mM Tris-HCl were incubated at 96 °C for 5 min, followed by six cycles of 30 s of sonication (Bioruptor Pico, Diagenode). Proteins were reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide in the dark. Each sample was loaded onto S-Trap microcolumns (Protifi) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, after loading, samples were washed with a 90:10 ratio (v/v) of methanol and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Samples were then digested with trypsin for 1.5 h at 47 °C. The digested peptides were eluted using 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate; trypsin was added to this fraction and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Two more elutions were made using 0.2% formic acid and 0.2% formic acid in 50% acetonitrile. The three eluents were pooled and vacuum dried. Samples were kept at −80 °C until analysis.

Ultra-LC–MS grade solvents were used for all chromatographic steps. Each sample was loaded using split-less nano-ultra performance LC (10K psi nanoAcquity; Waters). The mobile phase was H2O + 0.1% formic acid (A) then acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid (B). Desalting of the samples was performed online using a reversed-phase Symmetry C18 trapping column (180 µm internal diameter, 20 mm length, 5 µm particle size; Waters). The peptides were then separated using a T3 HSS nano-column (75 µm internal diameter, 250 mm length, 1.8 µm particle size; Waters) at 0.35 µl min–1. Peptides were eluted from the column into the mass spectrometer using the following gradient: 4% to 35% B in 120 min, 35% to 90% B in 5 min, maintained at 90% for 5 min and then back to initial conditions.

The nanoLC (Ultimate3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was coupled online through a nESI emitter (10 μm tip; FossilIonTech) to a quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Exploris480, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Data were acquired in data-dependent acquisition mode, using a Top10 method. MS1 resolution was set to 70,000 (at 400 m/z), a mass range of 375–1,650 m/z, automatic gain control (AGC) of 3 × 106 and the maximum injection time was set to 100 ms. MS2 resolution was set to 17,500, quadrupole isolation 1.7 m/z, AGC of 1 × 105, dynamic exclusion of 40 s and a maximum injection time of 150 ms.

MAPP data analysis and label-free quantification

Raw data were analysed in MaxQuant software96 (v.1.6.0.16) with the default parameters for the analysis of the proteasomal peptides, except for the following: unspecific enzyme, label-free quantification minimum ratio count of 1, minimum peptide length for unspecific search of 6, maximum peptide length for non-specific search of 40 and match between runs enabled. A false discovery rate of 1% was applied for peptide identification. For the analysis of tryptic digests, the default parameters were set, apart from a minimum peptide length of 6. Masses were searched against the human proteome database from UniProtKB (April 2020).

Peptides resulting from MaxQuant were initially filtered to remove reverse sequences and known MS contaminants. For the MAPP peptide fraction, we removed antibody and proteasome peptides as contaminants. To decrease ambiguity, we filtered out peptides that did not have at least two valid label-free quantification intensities, per condition. We included razor peptides, which belong to a unique MaxQuant ‘protein group’. MAPP protein intensities were inferred with MaxQuant. For graphical representation, intensities were log-transformed and zero intensity was imputed to a random value chosen from a normal distribution of 0.3 s.d. and downshifted by 1.8 s.d.

Peptide cleavage analysis

For each peptide, its absence or presence in each sample was annotated (scored 0 or 1) and the C-terminal amino acid was determined (N-terminal amino acid is the amino acid before the peptide start or cleavage site). Cysteines were not quantified as they might be affected by the crosslinker. Per sample, the relative frequency of each amino acid was calculated and standardized on the amino acid level for the heat map representation (z-scores). Heat maps were generated with the ComplexHeatmap (v.2.18.0) package with row clustering using Euclidean distances.

Activity assay of isolated proteasomes

Cells were lysed with 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP and 1:400 protease-inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem), homogenized through freeze–thaw cycles and passed through a needle (25G). The lysates were cleared by 30-min centrifugation at 21,130g at 4 °C. Protein concentration was assessed using a BC Assay Protein Quantitation Kit (Interchim). The immunoprecipitation was performed with Protein G–MagBeads (GeneScript) bound to PSMA1 proteasome subunit antibody, in a black 96-well plate and incubated overnight on an orbital shaker. The next day, the beads were washed three times in PBS and incubated in a reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM ATP). Proteasome activity was determined as previously described97, by cleavage of the fluorogenic precursor substrates Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC (Suc-LLVY-AMC) and Ac-Arg-Leu-Arg-AMC (Ac-RLR-AMC) (Bachem). The increase in fluorescence resulting from the degradation of peptide–AMC at 37 °C was monitored over time using a fluorometer (Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader, BioTek) at 340 nm excitation and 460 nm emission. The resulting product curves were followed for up to 3.5 h. Each fluorescence intensity represents a mean value obtained from three or more independent experiments.

Secretome analysis by MS

Analysis of secreted peptides was performed as previously described98. In brief, A549 cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in serum-free and phenol-red-free DMEM (Sartorius; 01-053-1 A) for 4 and 8 h. For dTAG secretome analysis, A549 cells expressing PPP1CB– and eGFP–dTAG (see above) were incubated in serum-free and phenol-red-free DMEM with DMSO or 500 nM of the dTAGV-1 compound for 6 h. Then, the medium was collected and a proteinase inhibitor (Calbiochem) was added. Then the medium was diluted in 80/20/0.1 ACN/H2O/formic acid (v/v/v) in a 1:7 ratio. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 14,000g at 4 °C 10 min. The supernatants were collected and dried. Peptides were then purified by C18 cartridges (Waters) and analysed by the LC–MS/MS as described above. The dTAG secretomes were analysed by MaxQuant (v.1.6.0.16). Identification of peptides in the A549 secretome was performed using FragPipe (v.22.0; MSFragger v.4.1, IonQuant v.1.10.27, Python v.3.8.13) according to the standard ‘non-specific-peptidome’ workflow with minor modifications. The raw data from both instruments were combined as two technical replicates per sample. The human reference proteome UP000005640 was used for peptide identification (uploaded 6 November 2024). The standard list of FragPipe contaminants was included. Methionine oxidation and N-terminal acetylation were used as variable modifications. Peptide length was set from 7 to 40 amino acids. The ‘split database’ parameter was set to 4 and match between runs (MBR) was used.

Notably, detection of PDDPs using peptidomics is challenging. Although MAPP-based proteasome profiling stabilizes peptides through cross-linking, enriches them through pull-down and achieves high purity and identification rates, extracellular peptidomics faces challenges owing to lower peptide stability, purity and identification rates caused by peptide variability, dynamic ranges and degradation factors. Furthermore, the overlap between MAPP and extracellular peptidomics is inherently limited, as PDDPs constitute less than 2% of proteasome-derived peptides and the extracellular environment reflects final stable peptide derivatives, often after additional cleavages. Therefore, only 11% of extracellular peptides are identical to MAPP-identified peptides, with 40% showing partial overlap, emphasizing the complementary yet distinct nature of these approaches (Fig. 2c).

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were performed at least twice, and in three biological replicates, unless otherwise stated. For each experiment, all compared conditions were analysed by MS at the same time to maintain comparability across samples and decrease batch effects.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.